About this report

This report is a thematic review of investigation reports by HSSIB and its predecessor organisation – the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB) – that included consideration of electronic patient record (EPR) systems. Throughout this report HSIB and HSSIB investigation reports will be collectively termed ‘HSSIB reports’.

EPR systems are software for collecting, storing and managing data about individual patients. The purpose of this report is to summarise and analyse HSSIB’s investigation findings relating to EPR systems, to identify themes arising from these investigations and to share any additional safety learning.

This report is not an investigation of EPR systems and only presents the evidence and themes as identified by previous HSSIB work. There are several areas related to EPR systems that HSSIB has not yet investigated and therefore they are not represented in this report.

This report includes technical language and its findings are intended for those responsible for procuring, configuring, integrating and optimising EPR systems in healthcare at national, regional and local levels. The findings may also be of interest to academics in digital healthcare, staff who use these systems, and patients. A glossary is provided in section 5.

Executive summary

Background

An electronic patient record (EPR) system is software for collecting, storing and managing data about individual patients. EPR systems are used across much of the NHS and their use is increasing with national aspirations for greater digitisation. EPR systems can improve patient care through supporting safety, efficiency and experience. However, EPR systems have also contributed to patient safety incidents.

This report summarises and analyses the findings of HSSIB’s investigations associated with EPR systems. Using a thematic approach, the review aimed to identify what EPR system components had been considered in reports, the problems associated with them, and their impact on patient safety. The review also revisited the safety recommendations and safety observations HSSIB had made that related to EPR systems.

Findings

The review found that EPR systems could contribute to the risks of patient care being missed, delayed or incorrect. These risks were persistent despite national recommendations and actions seeking to mitigate them.

Choosing an EPR system capable of meeting the needs of an organisation

- Where EPR systems did not have the functions an organisation needed or did not support the user (patients and staff), they had contributed to patient safety incidents.

- There were inconsistencies in the terms used in the design of health IT systems and their functions, such as usability and functionality, and limited guidance to support understanding of these concepts in EPR system design.

- Organisations did not always have a clear understanding of their requirements/needs for an EPR system, limiting their ability to match requirements to system capabilities (the things a system can do).

- When procuring EPR systems, organisations sometimes faced challenges understanding system capabilities and whether they met required national standards, such as for interoperability (the ability to work with other IT systems) and clinical risk management.

- National and regional support for organisations to identify their local requirements/needs to inform EPR system procurement was limited.

- Some EPR system procurement decisions were perceived by staff to be influenced by factors other than system capabilities, such as cost savings.

Implementing an EPR system that meets the needs of users

- Variation in governance processes for implementing EPR systems at national, regional and organisation levels meant associated risks to patient safety were not always identified and mitigated.

- Implementation of an EPR system was found to be a complex project that did not always effectively engage users to ensure it was safe and successful.

- Local configuration of EPR systems had the potential to introduce new risks to patient safety, with investigations identifying where this had occurred without the organisation recognising and mitigating against these risks.

- Factors contributing to an organisation’s ability to locally configure EPR systems included the capacity and capability of digital teams, the level of involvement of users in testing, support from manufacturers, and awareness and application of digital standards for clinical risk management.

- When users were involved in EPR system implementation they were not always representative of those using the system in practice, with difficulties faced releasing staff from clinical work to contribute to implementation.

- Several organisations faced challenges relating to the availability of working hardware and Wi-Fi connectivity to support the use of EPR systems in different clinical environments.

- Staff training in how to use an EPR system was often perceived to be limited. It did not always reflect how a system would be used in the ‘real world’, nor what to do if the EPR system failed.

Seeking feedback and ongoing EPR system optimisation

- Staff reported limited routes for raising concerns about poor functionality and usability of EPR systems, and limited action when concerns were reported that could impact on patient safety.

- Ongoing management of EPR systems, including upgrades and changes, did not always align with the digital standards for clinical risk management.

- EPR systems were not always kept up to date in line with national guidance and standards, or to reflect changes to internal care processes.

- Factors contributing to limited ongoing optimisation of EPR systems after initial implementation included the need to manage a range of local digital priorities, limited collaboration between digital and clinical teams, cost of upgrades, and limited resourcing for ongoing work and infrastructure.

- There were limited opportunities for organisations to share their experiences of implementing and optimising EPR systems for the benefit of other organisations.

HSSIB makes the following safety observation

Safety observation O/2025/079:

National bodies responsible for providing digital advice and guidance to NHS organisations can improve patient safety by clarifying consistent definitions for design-related IT terms – such as usability and functionality – and sharing guidance on how to apply design principles to electronic patient record system configuration and optimisation.

Local-level learning prompts

HSSIB investigations include local-level learning where this may help providers/organisations to identify and think about how to respond to specific patient safety issues at the local level. HSSIB has identified learning to help consider and mitigate risks around procuring, implementing and optimising EPR systems.

Supporting safe selection and procurement of an EPR system

- How does your organisation identify requirements for an EPR system to account for organisational and user (patients and staff) needs?

- How does your organisation identify whether an EPR system can perform the tasks needed to meet organisational requirements and meet expected national standards?

- How does your organisation identify whether an EPR system meets relevant standards, such as those that support clinical risk management and interoperability?

- How does your organisation ensure relevant information is requested from manufacturers and scrutinised during the selection and procurement of systems?

Supporting safe implementation of an EPR system

- Does your organisation understand the expectations for clinical risk management of health IT systems in relation to deployment, ensuring these are met and regularly reviewed?

- How does your organisation ensure representative user engagement and involvement in all aspects of the configuration, integration and ongoing optimisation of EPR systems?

- Does your organisation have a process for carrying out effective equality impact assessments to consider the needs of specific patient and staff groups who may be users of the EPR system?

- How does your organisation manage and oversee configuration changes to EPR systems to ensure they are appropriate, safe and successful?

- How does your organisation evaluate whether all necessary elements are in place before an EPR system is implemented or changed, for example through assessment of IT infrastructure and training?

Supporting ongoing optimisation of an EPR system

- How does your organisation proactively identify new and emerging risks associated with an EPR system, and ensure these are reviewed and mitigated as far as is practicable?

- Does your organisation have routes for staff to raise concerns about the EPR system they use, with feedback to inform staff of actions taken in response?

- Does your organisation have contingency plans and processes to maintain patient safety when there are EPR system problems, and are they shared with staff?

- How does your organisation share learning from the implementation and ongoing optimisation of EPR systems to support other organisations?

1. Background and context

This report summarises and analyses HSSIB’s investigation findings associated with electronic patient record (EPR) systems. It is the result of a review of all previous HSSIB and Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB) reports (published and in final draft) from 2018 to the end of May 2025. The review followed a thematic methodology which is described in appendix A.

1.1 Electronic patient record systems

1.1.1 Various terms are used to refer to software that stores and manages electronic healthcare data about individual patients. In England, the NHS commonly uses the term ‘electronic patient record’ or EPR to refer to this software. Other terms include electronic health records (EHRs) and electronic medical records (EMRs).

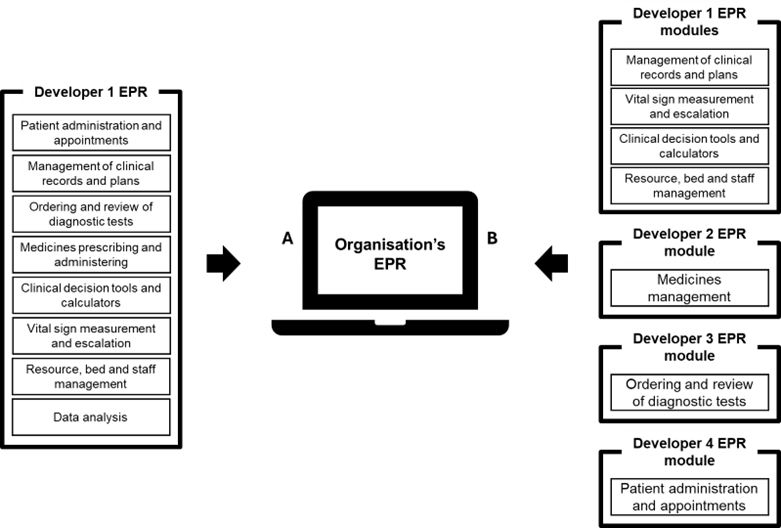

1.1.2 As shown in figure 1, an EPR system consists of several modules with different functions (NHS England Digital, 2024). A specific piece of software may provide one, some, or all of these modules.

Figure 1 EPR system modules

An EPR can be provided by a single piece of software (A), or by different modules from different developers (B)

Impact of EPR systems on patient care

1.1.3 The benefits of an EPR system include the support it can provide for safe and continuous patient care, decision making, medication management, resource management, co-ordination between services, and research (for example, The Health Foundation, 2025). An EPR can also increase efficiency and save staff time, enabling them to provide more face-to-face patient care (for example, The Health Foundation, 2024).

1.1.4 EPR systems have also been implicated as factors that have contributed to patient safety incidents (for example, Li et al, 2022; Nijor et al, 2022; Tewfik et al, 2024). Examples of harm and potential risks have been summarised by various sources, including by Patient Safety Learning (2024) in their report ‘Electronic patient record systems: putting patient safety at the heart of implementation’. In that report, examples were cited from HSSIB, NHS England, His Majesty’s Coroner and the media. In May 2024, the BBC also published an exploration of problems with EPR systems (Barbour et al, 2024). It identified that nearly half of trusts with an EPR system had reported issues, including three deaths across two trusts.

Digitisation of the NHS

1.1.5 The NHS has long recognised the benefits of digitisation for patient safety, care efficiency and effectiveness. Digitisation is the use of IT systems, data and electronic tools to support the delivery of healthcare. There are national ambitions to further digitise the NHS (Department of Health and Social Care, 2022; NHS, 2019), although EPR systems have long been used in some NHS sectors, such as general practice. Most hospitals also now have at least one EPR module in use.

1.1.6 More recent reports considering the state of care in the NHS in England have reiterated a need for greater digitisation. ‘Fit for the future: 10 year health plan for England’ describes a need to shift from ‘analogue to digital’ and includes recommendations to bring NHS technology up to date. The plan also includes a focus on digital access to care for patients, artificial intelligence, and interoperable health data (UK Government, 2025).

1.2 Digital terminology

1.2.1 Various terms are used when referring to EPR systems and their modules. In this report, the term EPR system is used when discussing findings relevant to multiple specific modules or an EPR system as a whole. Where a finding is related to a single and specific EPR module, this will be clearly described.

1.2.2 Various terms are also used when referring to the design of health IT systems. The glossary in section 5 summarises how key software terms were defined by this review, such as accessibility, usability, functionality and interoperability.

1.2.3 This report also refers to requirements, capabilities and standards. Requirements are the things an organisation needs from an EPR, while capabilities are what an EPR system is able to do. Standards are technical and operating conditions that software must meet to enable functionality such as interoperability. The NHS has a standards directory, which includes (NHS England, 2025):

- Information standards – ensure data is captured consistently and exchanged digitally. Examples include use of an international standard for clinical terminology via SNOMED (SCCI0034), use of the NHS number as the unique patient identifier in England and Wales (ISB0149), and standards for clinical risk and patient safety (see 1.2.4).

- Technical standards – specify how data is structured and transported between health IT systems. Examples include the use of specific messaging standards to exchange information (HL7 FHIR).

1.2.4 Data Coordination Board (DCB) 0129 and 0160 are two digital clinical safety standards (NHS England Digital, 2018a; 2018b); at the time of writing they are under review. They set out requirements for clinical risk management of health IT systems for manufacturers and organisations respectively. The standards refer to the role of clinical safety officers, competencies of digital personnel, risk management plans, issue logs and safety cases. Safety cases are reports that present arguments and evidence that a system is safe for a given application in a given environment (Liberati et al, 2024).

2. Patient safety issues – summary

The first step of the review was an analysis of the executive summaries of HSSIB’s investigation reports to identify findings that related to electronic patient record (EPR) systems. The approach taken is described in appendix A. This section answers the following questions:

- What EPR modules have been considered in the reports?

- What problems associated with EPR systems have been identified?

- What was the impact of those problems on patient safety?

Executive summaries of 112 investigation reports published between 2018 and 2025 were reviewed. Of these, 63 reports met the inclusion criteria for further analysis. A summary of the thematic coding used to inform this section is available in appendix B. HSSIB references in this section provide links to example reports.

2.1 EPR modules considered in reports

2.1.1 Reports often referred to EPR systems in general. However, on further exploration these investigations had only considered a single EPR module, such as for clinical records (HSSIB, 2024a). Several reports named the EPR module under consideration, such as for diagnostic tests (HSSIB, 2022a) or medications management (HSSIB, 2022b). Reports did not always acknowledge or describe whether the specific module was part of a wider EPR system or a standalone module. Several adjunct (supplementary), ‘bolt on’ or interfacing software programs were also considered; these were separate to but interacted with the EPR system, such as patient portals (HSSIB, 2024b).

2.1.2 Reports considered EPR systems across a range of healthcare sectors. Most investigations were in secondary care (acute hospitals, and urgent and emergency care) (HSSIB, 2025a) and where hospitals interacted with primary care (mostly general practice) (HSSIB, 2019). Investigations had also been undertaken in specific settings such as maternity (HSSIB, 2021a), mental health (HSSIB, 2025b) and prisons (HSSIB, 2025c).

2.2 Problems associated with EPR systems

2.2.1 Problems were considered to be factors related to EPR systems that had the potential to cause harm if not recognised and managed. Harm was considered broadly in relation to patients, staff and the organisation where the EPR system was used. The review identified that problems could be grouped under one or more of three high-level themes which are considered in turn below.

Design of the EPR system

2.2.2 Reports commonly described how the design of the EPR module under consideration had the potential to cause harm. ‘Design’ refers to how the EPR looked and functioned, and its capabilities. Problems associated with the accessibility, usability, functionality and interoperability of EPR systems were described; examples are provided in table 1.

Table 1 Examples of EPR system design problems

| Problem with | Example | Report |

|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | ‘… patients are not always able to access online tools and use online consultation due to their personal characteristics, social exclusion or deprivation.’ | HSSIB, 2024b |

| Usability | ‘… staff described … cluttered interfaces, no alerting of whether correspondence included critical information, and it being easy to choose a wrong action.’ | HSSIB, 2025a |

| Functionality | ‘The investigation found that ... there is no requirement for GP IT systems to consider continuity of care or to … ‘surface’ information to GPs when they see a patient with unresolving symptoms.’ | HSSIB, 2023a |

| Interoperability | ‘… local commissioning arrangements and the differing electronic systems in use led to a fragmented system. This resulted in information being held in isolation with suboptimal information transfer between [services].’ | HSSIB, 2021b |

2.2.3 The EPR systems and modules considered were known to have been developed by national or international developers; a small number were built in house to an organisation’s specifications. Where design problems were identified, these arose at both the initial design stage (HSSIB, 2024b) and when an EPR system had been adapted by a host organisation (HSSIB, 2022b). At organisation level, reports referred to the configuration and ongoing optimisation of EPR systems where digital teams refined a procured software to align with their organisation’s needs.

Implementation of EPR systems

2.2.4 Reports commonly described how the management of an EPR system’s implementation, whether as a whole or for a specific module, had the potential to cause harm. Implementation related to how the system was introduced into an organisation and included consideration of how it was integrated with existing systems and processes, and how the implementation project was managed (HSSIB, 2024b). Local configuration (described in 2.2.3) may be considered part of implementation.

Lack of an EPR system

2.2.5 Several reports also described where the absence of an EPR system, module or specific functionality did not support patient safety. Such absences also meant paper and IT systems were used alongside each other for patient care. Examples included where paper clinical notes were used with electronic prescribing and administration systems (HSSIB, 2021b), and where electronic notes were used with paper risk assessments (HSSIB, 2022c).

2.2.6 Where an EPR system, module or functionality was absent, reports were limited in their exploration of why there was an absence. Where factors were noted to be influencing the absence, these included limitations in financial resources, in local engagement with digital priorities and in IT infrastructure. Some reports noted that a module or functionality may exist but was not used because it did not meet the needs of users – for example, an electronic patient care handover system (HSSIB, 2023b).

2.3 The impact of EPR system problems

2.3.1 The impact of problems with EPR systems – that is, the resulting harm – was on patient safety, organisational efficiencies and wider national efforts to digitise healthcare. The safety of patients was put at risk by EPR systems where they created conditions within which a patient did not receive care, their care was delayed, or they received incorrect care including from being misidentified. A small number of reports also described how, once the wrong information was in a patient’s record, it was very difficult to rectify and this created an ongoing risk.

2.3.2 A recurrent scenario contributing to harm was when information needed for patient care could not be found in an EPR system – either because it was not available to the user (HSSIB, 2021c) or the user could not find it (HSSIB, 2024a). Some EPR systems also did not provide controls to mitigate known risks – for example, a lack of functionality to prevent inadvertent prescribing of an overdose of medication on a ward caring for children (HSSIB, 2022b).

2.3.3 Reports commonly described the potential for EPR system problems to cause physical and psychological harm to patients. Several reports showed how the problem had directly contributed to incidents of patient harm. Where harm was evidenced, contributory factors were the design (see vignette A) and implementation (see vignette B) of EPR systems. Further information about the vignettes is available via the cited reports.

Vignette A – weight-based medication errors in children (HSSIB, 2022b)

The patient, a girl aged 4 years, required blood-thinning medication. The clinical team agreed the patient should be prescribed 100 units/kg of the medication twice daily. The patient’s weight meant she required 1,520 units twice daily. The medication was inadvertently prescribed at a dose of 15,000 units twice daily using an electronic prescribing and medicines administration (ePMA) system. The ePMA system did not identify the incorrect prescription. The patient received five doses of the medication over 3 days and this contributed to bleeding around her brain.

The ePMA system had recently been introduced into the paediatric department following use on adult wards. When prescribing, the configuration of the ePMA system encouraged the selection of preferred strengths of the medication for adults. The prescriber selected an adult strength of the medication from a ‘quick list’. The system then relied on the doctor manually entering the correct dose, replacing the dose information that had been automatically entered by the system. This was not done correctly and functionality had not been configured to support safe prescribing of this medication to children.

Vignette B – electronic communications on patient discharge from acute hospitals (HSSIB, 2025a)

Following contact from a GP, a hospital identified several discharge summaries that had not been sent after patients had been discharged. The issue had been happening for around 1 year. The hospital reviewed all affected summaries and identified several near misses (where a patient had the potential to be harmed) and one incident that had led to harm.

The hospital’s investigation identified that the process for ‘sign-off’ of discharge summaries on the unit where the incident originated had not been clearly defined and was unclear to staff. The unit used the same EPR system as the rest of the trust, but the process for sign-off differed to that on other wards in the hospital.

2.3.4 A small number of reports described where an EPR system problem had the potential to disadvantage some patients depending on their individual circumstances. Examples included where the introduction of software had limited patients’ access to care, such as with online consultation software (HSSIB, 2024a), and where design and implementation was not inclusive of different local populations by recognising cultural (HSSIB, 2021d) and language (HSSIB, 2022a) differences.

Other forms of harm

2.3.5 From an organisation perspective, EPR system problems had resulted in adaptations where staff had looked to bypass difficult to use or inefficient EPR system design (HSSIB, 2022a). Design problems had also led to some care processes becoming more complex, requiring staff to carry out extra steps or tasks (HSSIB, 2025c).

2.3.6 Executive summaries did not describe the impact of EPR system problems on staff, but the review noted that full reports included examples of harm to staff. Examples included fatigue from the need to be vigilant when working with software and fear of making wrong decisions based on limited information contained within a system (HSSIB, 2024b).

3. Patient safety issues – contributory themes

Where HSSIB’s investigations considered electronic patient record (EPR) system design, configuration and implementation, the full reports were reviewed to answer the following question – what themes emerging from the investigations demonstrate factors relating to EPR systems that contributed to the patient safety issues?

Fifty full reports were reviewed to inform the findings of this section. The approach taken is described in appendix A. The review identified multiple factors that contributed to the patient safety issues and harm to patients. The following were found to be the most evidence-based contributory themes and these are explored with examples from reports:

- choosing an EPR system capable of meeting the needs of an organisation

- implementing an EPR system that meets the needs of users

- seeking feedback and ongoing EPR system optimisation.

A list of the included reports and a summary of the supporting thematic coding for this section are available in appendix C.

3.1 National context

3.1.1 The 50 reports were published between 2018 and 2025. This timeframe must be considered when interpreting the findings as the digital healthcare context has changed. During those 7 years there have been various national projects to transform digital healthcare, with the formation of, and further changes made to, digital oversight bodies. The digital maturity of individual organisations has also evolved (NHS England, 2023).

3.1.2 Despite the national changes and efforts to improve digital healthcare, this review identified that many of the problems described in the following sections have been consistent over the years. Recurrent digital problems included: poor usability and interoperability between different EPR systems and other software; poorly maintained hardware and outdated infrastructure impacting on system use; and limited available resources for the ongoing and safe use of EPR systems.

3.2 Choosing an EPR system capable of meeting the needs of an organisation

3.2.1 When procuring an EPR system, organisations may have multiple systems to choose from. For some procurements, national frameworks may help organisations understand the capabilities of the different EPR systems and whether a system complies with certain standards (see 1.2.3). Procuring software ‘on framework’ is encouraged because of the assurances provided by the framework – for example, the now expired GP IT Futures framework supported commissioning bodies and general practices to procure various IT systems (NHS England Digital, 2025).

3.2.2 This theme described where organisations had not been enabled to procure EPR systems that provided the capabilities they required. Some organisations did not have a clear understanding of their requirements for an EPR system. Such requirements included the tasks the organisation needed the system to achieve, the current and future needs for interfacing (interoperability) with other organisations’ systems (healthcare and non-healthcare), and the specific needs of local users (staff and patients). With several organisations looking to have a joint EPR system, reports also noted a need to understand requirements across a wide range of settings.

3.2.3 Some procurement decisions were perceived to be influenced by factors other than an EPR system’s capabilities and patient safety, including individual preferences, cost savings and strategic pressures.

Example – factors influencing procurement decisions (HSSIB, 2021a)

‘… the composition and membership of procurement teams varied considerably. Some trusts involved staff who use the equipment … One trust had a team led and directed by a senior clinician who individually decided on the best purchase which was then taken forward. Staff in the maternity department were not involved in the procurement process … Interoperability issues (issues relating to the ability of different IT systems to communicate and share data) were not fully considered.’

3.2.4 This theme also described where, even if organisations knew their requirements, they faced challenges knowing which EPR system to choose where no framework existed, or were restricted to procuring ‘on framework’ systems (see 3.2.1) that did not provide the capabilities they needed. The challenges of knowing which system to choose were contributed to by the range available and perceived transparency about their capabilities and compliance with national standards. Some organisations also had limited awareness of the expectations set for software developers to meet digital standards for clinical risk management (see 1.2.4) and so this did not always influence their choice.

3.2.5 Several investigations also found that support for organisations to help them make procurement decisions was limited. Where integrated care boards had not been involved in informing decisions, this impacted on wider interoperability across organisations in a region. Reports also described limited national guidance to help organisations make procurement decisions. However, national bodies also expressed concerns that any guidance could potentially endorse one EPR system over another which would be unfair.

Example – support for procurement decisions (HSSIB, 2024b)

‘… there is no guidance to support hospitals in their procurement of EPRs and no minimum expected standard of what critical patient information should be available and displayed within systems … The outcome of this, described by various stakeholders, was the procurement of systems that did not meet hospitals’ needs, systems that were unable to operate with others, and the need for future, costly additions to systems to update them.’

3.3 Implementing an EPR system that meets the needs of users

3.3.1 Following procurement, an EPR system needs to be implemented. Implementation actions described in reports included configuration of the EPR system, planning to integrate the system into local processes, and the launch of the system. This theme described where actions undertaken by organisations had not always achieved safe and effective implementation of an EPR system.

Configuration

3.3.2 ‘Configuration’ refers to the adaptation of a procured EPR system to meet local needs, aligned with an organisation’s processes and practices. Adaptations described in reports were for functionality and usability purposes, including: building workflows and document templates; refining interfaces to present information in different ways; designing customised alerts; and creating links with other IT systems.

3.3.3 Local configuration of EPR systems had the potential to introduce new risks to patient safety, with several reports identifying where this had occurred without the risks being recognised and mitigated. Factors contributing to the quality of local configuration included the capacity and capability of digital teams, involvement of users in testing changes, and awareness and application of digital standards for clinical risk management (see 1.2.4) when adapting an EPR system.

Example – application of digital standards (HSSIB, 2022b)

‘… the investigation asked those involved in the implementation of ePMA [electronic prescribing and medicines administration] systems whether they had safety cases in line with DCB160 [see 1.2.4]. One trust only had its original safety case for adult prescribing from the software manufacturer for the system, and not a local safety case for modifications or roll-out to paediatrics …’

3.3.4 Limited involvement of local users in configuration and testing was a recurrent finding across reports. There was variation in whether users, if involved, were representative of the staff who would be expected to use the EPR system in practice, and whether their feedback was acted on. Factors limiting effective user involvement included difficulty releasing staff from clinical work because of service pressures.

Integration

3.3.5 ‘Integration’ refers to the planning and management of how an EPR system is combined with the processes followed when delivering care. Integration was described in reports as ‘complex’ because of the need for a system to interact with people, processes and other technology (the wider sociotechnical system). Where integration approaches had not sought to understand the various interactions, EPR systems had not provided expected safety benefits, had led to unintended consequences, and had encouraged staff to deviate from expected processes through adaptations.

Example – integrating EPR systems alongside other processes (HSSIB, 2022a)

‘There is wide variation in practice in how unexpected significant radiological findings are communicated to clinicians … findings may be communicated by telephone, electronic or paper-based systems, and involve a variety of policies and procedures. It is often a multi-step process, involving a number of individuals and information systems; this increases the risk of errors.’

3.3.6 Associated problems with integration included whether there had been planning for when an EPR system was not working, and whether the supporting infrastructure had been fully considered to ensure it was supportive of a new EPR system. A common problem across the reports was the availability of functioning hardware, Wi-Fi connectivity and physical environments. These resulted in underuse of EPR systems and had contributed to incidents, including when staff had reverted to using paper notes and systems.

Example – influence of hardware and environment on EPR system use (HSSIB, 2024c)

‘Staff accessed the ePMA system either from static computers or using a computer on wheels. Medications were located in a medication room … Staff wrote down the medication required on a piece of paper, took the paper to the medication room. This was because the computer on wheels would not fit in the medication room and there was no computer in the room. They then prepared the medication based on the transcribed information …’

3.3.7 Factors contributing to integration problems were similar to those associated with configuration. They included capacity and capability of the teams involved, and the amount of user consultation when seeking to understand the realities and varieties of work in practice. There was under-recognition that healthcare is a ‘complex sociotechnical system’ and the impact of this on integration.

Launch

3.3.8 ‘Launch’ refers to the ‘go-live’ of an EPR system. Various approaches to EPR system launch were described, including ‘big bang’ (whole organisation together) and ‘incremental’ (parts of the organisation in sequence). The safety implications of the different approaches were not considered by the investigations, but it was identified that intended or assumed functionality had not always been available at the time of launch. Intended functionality included that which had been tested but was not included in the final product.

3.3.9 Where assumed functionality – such as to prevent inadvertent prescriptions – was not available, this had contributed to incidents. Assumptions had arisen because similar systems in other organisations had that functionality and because staff ‘expected’ functionality to be present. Several reports also described where added functionality to support patient care was underused because limited engagement with staff meant they were unaware of it.

Example – staff engagement and EPR system functionality (HSSIB, 2023c)

‘The trust learning disability policy described the need for ‘staff [to] ask and record’ the reasonable adjustments required by an individual in the comment box. The patient’s comment box was blank. Staff from several hospital departments told the investigation they were not aware they should be recording reasonable adjustments in this comment box. The investigation also saw and heard from staff that some were unaware of the flag [an on-screen alert to highlight important patient information within an electronic record] and did not routinely review them.’

3.3.10 Reports repeatedly described how limited initial and ongoing training in the use of an EPR system influenced staffs’ assumptions about and engagement with functionality. While it was acknowledged that any design should be intuitive, problems with functionality and usability meant local training was still required. Training did not always represent how the EPR system was used in the real world and was not taught by people with experience of using the system in clinical practice. There was also limited refresher training following introduction of new safety-critical functionality or updates to business continuity processes.

Example – awareness of safety-critical functionality (HSSIB, 2023b)

‘… clinical staff were not always aware of the functionality of their digital systems. For example, staff were not aware where EPRs had alerts for patients with similar names. Staff told the investigation that induction and training in systems was delivered locally, but did not equip staff with the knowledge they needed to use systems effectively.’

3.3.11 The amount of regional, national and developer support for launch of an EPR system was also explored by some investigations. There was limited guidance found to help organisations understand what they needed to consider for a successful launch, and limited guidance on how to sustain a safe EPR system. Some investigations also identified where there was support available, but it was unclear whether organisations were aware of these offers at regional and national levels.

3.4 Seeking feedback and ongoing EPR system optimisation

3.4.1 Following implementation, organisations need to understand the impact of the EPR system, keep it up to date and ensure it continues to meet the needs of users and the organisation. This theme described where organisations had not always explored the impact of an EPR system, managed problems that had been identified, or developed the system through optimisation.

Seeking feedback

3.4.2 ‘Feedback’ relates to the seeking of user perceptions about an EPR system and whether it is working as intended. Several reports found limited proactive efforts to seek and act on feedback, with assumptions being made that a lack of negative feedback meant a system was working safely and effectively.

Example – feedback on whether an EPR system is working (HSSIB, 2025a)

‘In several incidents the process issues were not recognised until a recipient had highlighted not receiving a discharge summary. This had led to ‘look backs’ where hospitals had identified multiple cases of unsent correspondence over a period of time, sometimes years. GPs also told the investigation that they were aware of several occasions where summaries had not been received but they had not informed the hospital.’

3.4.3 Several reports described where staff had concerns about the poor functionality and usability of an EPR system but had limited routes to report those concerns. Staff also described not always feeling listened to when they shared such issues. This included a repeated problem across several organisations where temporary staff were unable to gain access to the EPR system they needed to carry out their roles (HSSIB, 2024d).

3.4.4 Formal learning systems for the identification and mitigation of problems with EPR systems were found to not always be available or transparent, with limited sharing of experiences beyond individual organisations. As described in 3.3.3 in relation to configuration, organisations were not aligned with the expectations of digital standards for clinical risk management when deploying and optimising EPR systems.

Example – issue reporting and transparency (HSSIB, 2021a)

‘… faults were logged with the electronic patient record midwife (EPRM) as they had the contacts with the manufacturers. The EPRM kept a spreadsheet of all ‘tickets’ logged with faults that had been escalated to the manufacturer. However, this spreadsheet was kept on a shared device within the maternity department and was therefore not visible to anyone outside of the department, including IT or medical engineering staff.’

Optimising the EPR system

3.4.5 ‘Optimisation’ refers to changes to an EPR system’s configuration and/or aligned processes in light of feedback, emerging issues and changing circumstances. Several reports described where a system had not been kept up to date in line with national guidance and standards. Examples included where systems had not been configured against new standards to support interoperability, and where clinical decision making functionality had not been updated to reflect changes in clinical guidance.

Example – updating EPR systems in response to changes in guidance (HSSIB, 2025b)

‘Staff in providers also told the investigation that their EPRs did not facilitate good person-centred safety assessment, care planning with patients and carers, or handover of patient information ... some EPRs still required staff to categorise patient risk assessments despite recommendations suggesting the need to move away from this type of risk stratification.’

3.4.6 Factors contributing to under optimisation of an organisation’s EPR system included the lack of capacity within digital teams, the range of local IT priorities they had to manage, the quality of collaboration between digital and clinical teams to identify development needs, and limited resources for the ongoing optimisation of systems and infrastructure. A lack of user involvement in optimisation was again described, with some reports noting that once an EPR system was launched, there was limited ongoing consideration of the need to develop it with the staff who use it.

3.4.7 Resourcing for the upkeep of IT systems was also noted to be a problem by several reports. This included for developing EPR software, building interoperability with systems introduced later, and to maintain the IT infrastructure. Reports described under-recognition of the long-term cost implications of optimisation to keep a system running safely and effectively, and limited funding to ensure this happened.

3.5 Summary

3.5.1 The review found a commonality across the above themes – they relate to the governance of EPR systems. ‘Governance’ refers to the processes and structures within and across organisations that support effective decision making in the design, selection, configuration, implementation, optimisation and oversight of an EPR system.

3.5.2 Governance includes ensuring accountabilities and responsibilities are clear and achieved – such as those described in digital standards for clinical risk management of health IT systems (NHS England Digital, 2018a; 2018b) – and ensuring that user input is sought and applied. Where governance had not been effective, patient safety issues and incidents relating to EPR systems were seen in HSSIB’s investigations.

4. Learning from HSSIB’s investigations

The findings of this report are highly relevant at a time when the NHS long-term plan is looking to digitisation to address several quality issues facing healthcare, including with efficiency and patient experience (UK Government, 2025). HSSIB’s investigations demonstrate the widespread use of electronic patient record (EPR) systems but also the persistent EPR-related patient safety issues that exist despite recognition of contributory factors and resulting actions.

This section briefly summarises and reiterates the safety recommendations and safety observations HSSIB has made to support improvements in EPR-related patient safety. It also describes the new learning arising from this review and sets out additional local-level prompts to help further share the learning from HSSIB’s investigations with organisations.

4.1 HSSIB’s safety recommendations and safety observations

4.1.1 Several of the HSSIB investigations included in this review made safety recommendations to national bodies to inform change across the healthcare system for the benefit of patient safety. They also made safety observations for the benefit of patient safety to be considered by organisations and bodies at local, regional and national levels.

4.1.2 For this review, these safety recommendations and safety observations were coded to identify where they sought to influence the EPR-related patient safety issues described in section 3; the supporting coding is available in appendix D. Of the 50 reports in the review, 28 included relevant safety recommendations (n=29) and safety observations (n=26).

Safety recommendations

4.1.3 Safety recommendations were commonly aimed at influencing the design of EPR systems and therefore increasing the availability of procurable systems capable of meeting organisations’ needs (see 3.2). These safety recommendations suggested that national bodies develop or update standards or specifications to ensure systems can provide the required functionality. A small number were also aimed at supporting procurement decisions.

Example – influencing standard development (HSSIB, 2019)

R/2019/051: It is recommended that NHSX supports the development of interoperability standards for medication messaging.

Example – influencing procurement (HSSIB, 2025c)

R/2025/070: HSSIB recommends that NHS England/Department of Health and Social Care includes within its healthcare IT procurement system specification the need to support interoperability between the operational prison IT systems and any future prison healthcare IT system.

4.1.4 Some of the safety recommendations aimed to influence how national bodies support local organisations when implementing EPR systems (see 3.3). They recommended the seeking of national support for adoption of technology and the providing of guidance for implementation. There were limited safety recommendations aimed at local configuration and optimisation of EPR systems.

Example – influencing local implementation (HSSIB, 2024b)

R/2024/031: HSSIB recommends that NHS England develops mechanisms for assuring that integrated care boards support general practices when implementing online consultation. This is to ensure online consultation tools are procured and implemented in ways that best support patient safety.

4.1.5 Several safety recommendations aimed to influence the safety and risk governance surrounding EPR systems (see 3.5). These included recommendations to influence the identification of associated risks with new or changed EPR systems, and to encourage incident/issue reporting. The review noted that some of the safety recommendations referred to existing guidance and standards, suggesting challenges with the implementation of the standards themselves.

Example – influencing uptake of governance standards (HSSIB, 2022b)

R/2022/178: HSIB recommends that NHS Digital and NHSX promote the organisational requirements for digital clinical safety, including organisations’ responsibilities in terms of safety cases and clinical safety officers, to encompass system functionality and processes.

4.1.6 HSSIB publishes responses to its safety recommendations. The review noted that some of the bodies the safety recommendations were made to no longer exist and it was also not clear whether some planned actions in response to safety recommendations had progressed. Nationally it has been recognised that the NHS receives multiple safety recommendations from different sources creating challenges for the healthcare system (Dash, 2025). HSSIB is working collaboratively with other national bodies to develop guidance on the creation and implementation of safety recommendations, and to create more formal oversight and management of national recommendations (HSSIB, 2024e).

Safety observations

4.1.7 Safety observations more commonly aimed to influence the way EPR systems are implemented and optimised within organisations. They included learning to inform configuration to meet the needs of users.

Example – influencing local configuration (HSSIB, 2023c)

O/2023/002: Health and care providers can improve patient safety by ensuring that local configuration of electronic patient record systems consider the accessibility and usability of the digital record reasonable adjustments flag in patient records.

4.1.8 Observations also included learning for organisations to consider when they are integrating an EPR system into practice. Considerations included the assessment of local infrastructure and organisational readiness for new technology, and the inclusion of users throughout the integration.

Example – influencing local integration considerations (HSSIB, 2023b)

O/2023/205: It may be beneficial for healthcare organisations to assess their information technology infrastructure needs, such as equipment availability and network coverage, to enable staff to consistently access critical patient information.

4.2 Safety learning arising from this review

4.2.1 As described in 3.5, the governance surrounding EPR systems was a clear theme emerging from this review. From a national governance perspective, HSSIB has launched work to examine aspects of governance for EPR systems through the lens of electronic prescribing and medicine administration functionality (HSSIB, n.d.).

4.2.2 During this review, inconsistencies were identified in what was considered an EPR system and how digital terms – such as usability, functionality and accessibility – were defined. As described in 2.1, these inconsistences also meant it was sometimes unclear whether investigations were considering a whole EPR system or a specific module (see figure 1).

4.2.3 The variation in definitions of different digital terms meant that a problem may have been labelled incorrectly in reports. To help with consistency in this report the definitions in the glossary were developed, taking insights from national documents and international standards. However, the review was unable to identify a single source clearly defining each term.

HSSIB makes the following safety observation

Safety observation O/2025/079: National bodies responsible for providing digital advice and guidance to NHS organisations can improve patient safety by clarifying consistent definitions for design-related IT terms – such as usability and functionality – and sharing guidance on how to apply design principles to electronic patient record system configuration and optimisation.

Local-level learning

4.2.4 HSSIB investigations often include local-level learning where this may help providers/organisations to identify and think about how to respond to specific patient safety issues at the local level. This review identified learning to help think about and mitigate risks associated with implementing EPR systems into organisations and their ongoing optimisation. These may also be beneficial to consider when looking to enhance wider aspects of quality through digital healthcare, including efficiency and patient experience.

Local-level learning prompts

Supporting safe selection and procurement of an EPR system

- How does your organisation identify requirements for an EPR system to account for organisational and user (patients and staff) needs?

- How does your organisation identify whether an EPR system can perform the tasks needed to meet organisational requirements and meet expected national standards?

- How does your organisation identify whether an EPR system meets relevant standards, such as those that support clinical risk management and interoperability?

- How does your organisation ensure relevant information is requested from manufacturers and scrutinised during the selection and procurement of systems?

Supporting safe implementation of an EPR system

- Does your organisation understand the expectations for clinical risk management of health IT systems in relation to deployment, ensuring these are met and regularly reviewed?

- How does your organisation ensure representative user engagement and involvement in all aspects of the configuration, integration and ongoing optimisation of EPR systems?

- Does your organisation have a process for carrying out effective equality impact assessments to consider the needs of specific patient and staff groups who may be users of the EPR system?

- How does your organisation manage and oversee configuration changes to EPR systems to ensure they are appropriate, safe and successful?

- How does your organisation evaluate whether all necessary elements are in place before an EPR system is implemented or changed, for example through assessment of IT infrastructure and training?

Supporting ongoing optimisation of an EPR system

- How does your organisation proactively identify new and emerging risks associated with an EPR system, and ensure these are reviewed and mitigated as far as is practicable?

- Does your organisation have routes for staff to raise concerns about the EPR system they use, with feedback to inform staff of actions taken in response?

- Does your organisation have contingency plans and processes to maintain patient safety when there are EPR system problems, and are they shared with staff?

- How does your organisation share learning from the implementation and ongoing optimisation of EPR systems to support other organisations?

5. Glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Accessibility | How something, such as an EPR system, can be used by people with ‘the widest range of user needs, characteristics and capabilities’ (International Organization for Standardization, 2019). |

| Assurance | Safety assurance involves the monitoring and measuring of safety performance, evaluating how effectively an organisation is managing risks, and the continuous improvement of safety (International Civil Aviation Organization, 2018). |

| Capabilities | What a piece of software is able to do, including what tasks it performs for the user to support the delivery of care. |

| Configuration (of an EPR system) | In this report, configuration refers to how an organisation takes a procured EPR system and sets it up for specific use within its own context. |

| Design (of an EPR system) | Design is the development of a concept and then creation of a product. In this report, design refers to the initial development and creation of an EPR system by the manufacturer. |

| Digital healthcare | The use of IT systems, data and other digital tools to support the delivery of healthcare and to support high-quality patient outcomes. |

| Digital maturity | The extent to which an organisation has embraced and implemented digital healthcare to support and improve care. |

| Electronic patient record (EPR) system | Software for collecting, storing and managing data about individual patients (NHS England Digital, 2024). |

| Function | A feature that performs a task in an IT system. |

| Functionality | The features of an IT system, such as an EPR system, and its ability to enable users to achieve their goal. |

| Hardware | The physical parts of IT systems, such as servers, laptops, handheld devices and monitors. It also includes the supporting infrastructure, such as Wi-Fi. |

| Health IT system | Product used to provide electronic information for health or social care purposes. The product may be hardware, software or a combination (NHS England Digital, 2018b). |

| Implementation | Processes for putting a plan, such as for a new EPR system, into place. In this report, these processes include EPR system configuration, integration, launch and ongoing support. |

| Integration | Combining a system, such as an EPR system, with other systems, processes and components to work together. |

| Interoperability | The ability of a system, such as an EPR system, to work with other systems without special effort (International Organization for Standardization, 2021). |

| IT systems | The computer systems, hardware, software and networks in an organisation. |

| Optimisation | A continuous process which improves an EPR system's usability and functionality over time (NHS Providers, 2025). It may include adding or removing functionality, or making it simpler to use. |

| Procurement | The process of identifying and acquiring goods and services from other sources, such as software manufacturers. |

| Requirements | A organisation’s (documented) description of what a system, such as an EPR system, should do and what it needs to provide for users and organisations. |

| Software | Components of IT systems including programs, procedures and routines that instruct hardware on how to run tasks. |

| Standards | A set of technical and operating conditions that software must meet. |

| Usability | How a product, such as an EPR system, can be used by users to achieve goals with effectiveness, efficiency and safety (International Organization for Standardization, 2018). Various authors have described usability principles which include consistency, prevention of errors and minimalist design (Nielsen, 1994). |

| User | A person who uses a product, such as an EPR system (International Organization for Standardization, 2018). This includes patients, carers and staff. |

| User-interface | The parts of a health IT system, such as an EPR system, that users interact with and enter information into (International Organization for Standardization, 2019). |

6. References

Barbour, S., Wright, N., et al. (2024) NHS computer problems put patients at risk of harm. BBC News, 30 May. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c4nn0vl2e78o (Accessed 2 January 2025).

Dash, P. (2025) Review of patient safety across the health and care landscape. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-patient-safety-across-the-health-and-care-landscape (Accessed 6 August 2025).

Department of Health and Social Care (2022) A plan for digital health and social care. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-plan-for-digital-health-and-social-care/a-plan-for-digital-health-and-social-care (Accessed 2 January 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (n.d.) Medication related harm. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/medication-related-harm/ (Accessed 6 August 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2019) Electronic prescribing and medicines administration systems and safe discharge. (Originally published by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch) Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/electronic-prescribing-and-medicines-administration-systems-and-safe-discharge/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2021a) Suitability of equipment and technology used for continuous fetal heart rate monitoring. (Originally published by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch) Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/suitability-of-equipment-and-technology-used-for-continuous-fetal-heart-rate-monitoring/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2021b) Management of chronic asthma in children aged 16 years and under. (Originally published by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch) Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/management-of-chronic-asthma-in-children-aged-16-years-and-under/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2021c) Surgical care of NHS patients in independent hospitals. (Originally published by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch) Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/surgical-care-of-nhs-patients-in-independent-hospitals/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2021d) Local integrated investigation pilot 1: incorrect patient identification. (Originally published by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch) Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/hsib-local-integrated-investigation-pilot/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2022a) Clinical investigation booking systems failures: written communications in community languages. (Originally published by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch) Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/clinical-investigation-booking-systems-failures-written-communications-in-community-languages/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2022b) Weight-based medication errors in children. (Originally published by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch) Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/weight-based-medication-errors-in-children/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2022c) The assessment of venous thromboembolism risks associated with pregnancy and the postnatal period. (Originally published by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch) Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/the-assessment-of-venous-thromboembolism-risks-associated-with-pregnancy-and-postnatal/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2023a) Continuity of care: delayed diagnosis in GP practices. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/continuity-of-care-delayed-diagnosis-in-gp-practices/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2023b) Access to critical patient information at the bedside. (Originally published by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch) Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/access-to-critical-patient-information-at-the-bedside/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2023c) Caring for adults with a learning disability in acute hospitals. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/caring-for-adults-with-learning-disabilities-in-acute-hospitals/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2024a) Mental health inpatient settings: creating conditions for the delivery of safe and therapeutic care to adults. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/mental-health-inpatient-settings/investigation-report/ (Accessed 1 August 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2024b) Workforce and patient safety: digital tools for online consultation in general practice. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/workforce-and-patient-safety/second-investigation-report/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2024c) Medication not given: administration of time critical medication in the emergency department. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/medication-related-harm/investigation-report/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2024d) Workforce and patient safety: temporary staff – integration into healthcare providers. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/workforce-and-patient-safety/third-investigation-report/ (Accessed 15 August 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2024e) Recommendations but no action: improving the effectiveness of quality and safety recommendations in healthcare. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/recommendations-but-no-action-improving-the-effectiveness-of-quality-and-safety-recommendations-in-healthcare/ (Accessed 6 August 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2025a) Workforce and patient safety: electronic communications on patient discharge from acute hospitals. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/workforce-and-patient-safety/fifth-investigation-report/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2025b) Mental health inpatient settings: overarching report of investigations directed by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/mental-health-inpatient-settings/fifth-investigation-report/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2025c) Healthcare provision in prisons: data sharing and IT. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/healthcare-provision-in-prisons/third-investigation-report/ (Accessed 30 July 2025).

International Civil Aviation Organization (2018) Safety management manual. Doc 9859. 4th edition. Available at https://elibrary.icao.int/product/229751 (Accessed 19 September 2025).

International Organization for Standardization (2018) Ergonomics of human-system interaction Part 11: Usability: definitions and concepts. ISO 9241-11:2018. Available at https://www.iso.org/standard/63500.html (Accessed 8 August 2025).

International Organization for Standardization (2019) Ergonomics of human-system interaction Part 210: Human-centred design for interactive systems. ISO 9241-210:2019. Available at https://www.iso.org/standard/77520.html (Accessed 1 August 2025).

International Organization for Standardization (2021) Health informatics – Interoperability and integration reference architecture – Model and framework. ISO 23903:2021. Available at https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:23903:ed-1:v2:en (Accessed 8 August 2025).

Li, E., Clarke, J., et al. (2022) The impact of electronic health record interoperability on safety and quality of care in high-income countries: systematic review, Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(9), e38144. doi: 10.2196/38144

Liberati, E.G., Martin, G.P., et al. (2024) What can safety cases offer for patient safety? A multisite case study, BMJ Quality & Safety, 33(3), pp. 156–165. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2023-016042

NHS (2019) The NHS Long Term Plan. Available at https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20230418155402/https:/www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/ (Accessed 18 September 2025).

NHS England (2023) Digital maturity assessment. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/digitaltechnology/connecteddigitalsystems/digital-maturity-assessment/ (Accessed 2 January 2025).

NHS England (2025) Standards directory. Available at https://standards.nhs.uk/ (Accessed 9 October 2025).

NHS England Digital (2018a) DCB0129: Clinical risk management: its application in the manufacture of health IT systems. Available at https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/information-standards/governance/latest-activity/standards-and-collections/dcb0129-clinical-risk-management-its-application-in-the-manufacture-of-health-it-systems (Accessed 1 August 2025).

NHS England Digital (2018b) DCB0160: Clinical risk management: its application in the deployment and use of health IT systems. Available at https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/information-standards/governance/latest-activity/standards-and-collections/dcb0160-clinical-risk-management-its-application-in-the-deployment-and-use-of-health-it-systems (Accessed 1 August 2025).

NHS England Digital (2024) Building healthcare software – acute, community and mental health care. Available at https://digital.nhs.uk/developer/guides-and-documentation/building-healthcare-software/acute-community-and-mental-health-care (Accessed 2 January 2025).

NHS England Digital (2025) Catalogue solutions. Available at https://buyingcatalogue.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue-solutions (Accessed 1 August 2025).

NHS Providers (2025) What is optimisation? Available at https://nhsproviders.org/resources/making-the-most-of-your-electronic-patient-record-system/what-is-optimisation (Accessed 9 October 2025).

Nielsen, J. (1994) Enhancing the explanatory power of usability heuristics. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, USA. doi: 10.1145/191666.191729

Nijor, S., Rallis, G., et al. (2022) Patient safety issues from information overload in electronic medical records, Journal of Patient Safety, 18(6), e999–e1003. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000001002

Patient Safety Learning (2024) Electronic patient record systems: putting patient safety at the heart of implementation. Available at https://www.pslhub.org/learn/patient-safety-learning/electronic-patient-record-systems-putting-patient-safety-at-the-heart-of-implementation-patient-safety-learning-31-july-2024-r11859/ (Accessed 10 October 2025).

Tewfik, G., Rivoli, S., et al. (2024) The electronic health record: does it enhance or distract from patient safety?, Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology, 37(6), pp. 676–682. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000001429

The Health Foundation (2024) Which technologies offer the biggest opportunities to save time in the NHS? Available at https://www.health.org.uk/reports-and-analysis/briefings/which-technologies-offer-the-biggest-opportunities-to-save-time-in#lf-section-214226-anchor (Accessed 23 July 2025).

The Health Foundation (2025) Electronic patient records: why the NHS urgently needs a strategy to reap the benefits. Available at https://www.health.org.uk/reports-and-analysis/analysis/electronic-patient-records-nhs-strategy (Accessed 15 August 2025).

UK Government (2025) Fit for the future: 10 year health plan for England. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/10-year-health-plan-for-england-fit-for-the-future (Accessed 22 August 2025).

7. Appendix A – review approach

Aim and objectives of the review

The review aimed to summarise and analyse HSSIB/HSIB’s investigation findings in relation to electronic patient record (EPR) systems. The review objectives were to answer the following questions:

- what EPR modules have been considered in the reports?

- what problems associated with EPR systems have been repeatedly identified?

- what was the impact of those problems on patient safety?

- what themes have emerged from the investigations to demonstrate factors contributing to the patient safety issues with EPR systems?

- what safety recommendations and safety observations have HSSIB/HSIB made to support improvements in EPR-related patient safety?

Review sample

All HSSIB and HSIB investigation and learning reports published and in final draft at the end of May 2025 were included in the review. The sample was refined, in line with the analysis approach, to reports that considered EPR systems to any degree. An EPR system:

- was considered as software that collects, stores and supports management of clinical information about an individual patient in a healthcare provider organisation

- could be a single piece of software offering multiple capabilities or separate specific modules provided by different software

- included modules for: patient administration and appointments; management of records, assessments and plans; diagnostics and test ordering/receipt of results; ordering and management of medications; and decision support

- did not include modules for resource management or business analytics.

Analysis approach

Qualitative research principles were used and a template analysis methodology was applied. Three rounds of coding were undertaken by two HSSIB reviewers, followed by a refinement and theme description round.

Round 1

The reviewers coded 40 reports to develop a template for the further coding. The initial template is shown in appendix B and this was used for round 2.

Round 2

All executive summaries (n=112) were reviewed between the reviewers. Where summaries included consideration of EPR systems they were coded against the template. Where they did not refer to EPR systems, a free-text search for key words was undertaken to identify relevant reports. Where key words were found, reports were coded to the template. Any reports for exclusion were checked by the second reviewer.

Following round 2 coding, the reviewers met to examine emerging themes across the included reports (n= 63). This led to the findings described in section 2 and agreement of the focus for round 3.

Round 3

All full reports relating to the design, configuration and implementation of EPR systems (identified in round 2) were collated and coded (n=50). The reviewers reviewed half of the reports each, with 10% being reviewed by both. The reviewers met regularly to discuss findings, the code set and emerging themes.

Refinement

The reviewers met to analyse the coding and refine the focus for section 3 of this report. At this point, safety recommendations and safety observations made in included reports were compared with the coding to identify where HSSIB had looked to influence improvements.

Ensuring trustworthy findings

The following aimed to support the trustworthiness of the findings of this review:

- Two reviewers worked independently and collaboratively to agree the coding. Both were familiar with qualitative research techniques.

- Findings were presented internally to those who carried out the source investigations with discussion of findings.

- Findings were shared with stakeholders during consultation and prior to publication.

- Reflexive practice was undertaken throughout.

Stakeholder engagement

Prior to publication this report was shared with internal and external stakeholders to HSSIB, including those who engaged with HSSIB while the review was being carried out. The report was also shared with national bodies including:

- Department of Health and Social Care

- NHS England

- Care Quality Commission

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

- Patient Safety Learning.

8. Appendix B – supplementary information for section 2

The table below is a summary of the top codes informing the findings in section 2.

| Name | Number of reports |

|---|---|

| 1. Included reports | 63 |

| - EPR component considered | 63 |

| -- EPR – general reference | 31 |

| -- EPR – specific component | 30 |

| -- EPR – interfacing element | 24 |

| -- EPR – infrastructure | 6 |

| 2. EPR problem identified in reports | 63 |

| - Design of the EPR is the problem | 38 |

| - Implementation of the EPR is the problem | 31 |

| - Lack of an EPR is the problem | 26 |

| 3. Impact of EPR problem in reports | 63 |

| - Patient safety | 52 |

| - Organisational | 29 |

| - National/wider system | 14 |

| - Unclear | 5 |

| - Staff | 0 |

9. Appendix C – supplementary information for section 3

The following HSSIB/HSIB investigation reports informed the findings in section 3:

- Access to critical patient information at the bedside

- Caring for adults with a learning disability in acute hospitals

- Clinical investigation booking systems failures: written communications in community languages

- Continuity of care: delayed diagnosis in GP practices

- Digital tools for online consultation in general practice

- Electronic prescribing and medicines administration systems and safe discharge

- Failures in communication or follow-up of unexpected significant radiological findings

- Healthcare provision in prisons: data sharing and IT

- Insertion of an incorrect intraocular lens

- Invasive procedures in patients with sickle cell disease

- Local integrated investigation pilot 1

- Management of chronic asthma in children aged 16 years and under

- Management of chronic health conditions in prisons

- Maternity pre-arrival instructions by 999 call handlers

- Medication not given: administration of time critical medication in the emergency department

- Medication not given: anticoagulation before and after a procedure

- Medicine omissions in learning disability secure units

- Mental health inpatient settings: creating conditions for the delivery of safe and therapeutic care to adults

- Mental health inpatient settings: overarching report of investigations directed by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care

- Nutrition management of acutely unwell patients in acute medical units

- Outpatient appointments intended but not booked after inpatient stays

- Placement of nasogastric tubes

- Positive patient identification

- Potential under-recognised risk of harm from the use of propranolol

- Procurement, usability and adoption of ‘smart’ infusion pumps

- Recognising and responding to critically unwell patients

- Residual drugs in intravenous cannulae and extension lines

- Risks to medication delivery using ambulatory infusion pumps

- Safety risk of air embolus associated with central venous catheters used for haemodialysis treatment

- Sepsis: a patient with a urine infection

- Sepsis: a patient with abdominal pain

- Sepsis: a patient with diabetes and a foot infection

- Suitability of equipment and technology used for continuous fetal heart rate monitoring

- Surgical care of NHS patients in independent hospitals

- The assessment of venous thromboembolism risks associated with pregnancy and the postnatal period

- The selection and insertion of vascular grafts in haemodialysis patients

- The use of an appropriate flush fluid with arterial lines

- Timely detection and treatment of cauda equina syndrome

- Transfer of critically ill adults

- Undetected button/coin cell battery ingestion in children