A note of acknowledgement

We would like to thank the many people who contributed to this report. From a patient and public perspective, thank you to those who attended focus groups that helped inform the focus of this investigation. Thank you also to the families we met throughout the investigation who shared their very personal experiences. The experiences we heard describe the human impact of the risks explored in this report and demonstrate the importance of improving patient safety.

It is also important to recognise that this investigation was undertaken at a time of significant pressure on all parts of the NHS and while long-term plans were evolving. We are grateful to all those who supported our work alongside meeting the wider ongoing challenges.

About this report

This investigation report is published under HSSIB’s workforce and patient safety theme. The theme was launched by HSSIB’s predecessor organisation, the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch, and was therefore completed under The NHS England (Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch) Directions 2022.

This report is intended for healthcare policy makers to help influence improvements in patient safety. It is also intended for those who work in and engage with providers of primary, community and secondary care, including integrated care boards (ICBs). While the investigation did not focus on transfers of care between other health and social care settings, findings are likely to be relevant to these providers.

This report includes technical language and a glossary is provided in section 5. The report specifically refers to ‘integration’ and ‘interoperability’, and in the context of this report these terms are defined as follows:

- Integration – bringing together different providers to deliver care in a joined-up and co-ordinated way so patients receive the ongoing care they need.

- Interoperability – the ability of IT systems to work with other IT systems without special effort to enable communication of information within/between providers.

After starting this investigation, HSSIB launched a thematic review of its previous publications that have considered electronic patient records (EPRs). This investigation will contribute to that thematic review as it identified several findings related to the design and implementation of EPRs and interoperability.

Executive summary

Background

This investigation explored the patient safety risks associated with the communication of critical clinical information when patients are discharged from acute hospital inpatient settings, and the follow-up of ongoing actions for patients by primary and community care.

Discharge from hospital represents a transition of care from one provider (the hospital) to others (such as general practice, pharmacy and/or community care). To support patient safety, critical clinical information about the patient needs to flow between providers to ensure care after discharge is timely and appropriate. The main method for communicating information on discharge from hospitals is the electronic discharge summary. This provides an overview of why the patient was in hospital, what happened during the admission, and plans for their ongoing care.

This investigation considered communication processes between providers on discharge of patients from hospital, and how the use of electronic correspondence impacts on these processes. If critical clinical information is not communicated effectively at transitions of care, patients may come to harm by missing or receiving incorrect care. Patients and healthcare staff described multiple incidents of harm following discharge because of problems with the communication of information.

Findings

- Patients are coming to harm where follow-up actions are needed after discharge from hospital and discharge planning has not accounted for constraints and challenges in the local health and care system (referred to here as ‘the local system’). This means actions are not always undertaken or completed within expected timeframes.

- A lack of integration – as evidenced by limited collaboration between primary, community and secondary care providers – contributes to discharge planning and communications that do not always ensure patients receive continuity in their care.

- Risks to patient safety associated with the quality and timeliness of discharge correspondence, most notably the discharge summary, have been “normalised”. There is unclear accountability for the safety of patients early after discharge.

- The current regulatory approach for inspection of care quality does not lend itself to effective scrutiny of cross-provider pathways, such as transitions of care between providers.

- Oversight mechanisms in providers and integrated care boards do not always exist or function to ensure that end-to-end discharge communication is achieved through the creation, sending, receipt and actioning of correspondence.

- A lack of interoperability between IT systems within and across providers means information does not pass seamlessly, increasing the risk of information being lost, delayed or missed.

- The design/configuration of the parts of electronic patient record for correspondence, including discharge summaries, can introduce the potential for errors and does not always support staff to create, send and process correspondence.

- Discharge correspondence may not be accurate in scenarios where patients continue to receive care in hospital after discharge correspondence has been sent.

- Discharge summaries are not actively sent to, or accessible to, all the providers of ongoing care who need to know the clinical information they contain.

- The content of discharge correspondence, including discharge summaries, does not always meet the information needs of recipients to ensure safety-critical actions for a patient’s ongoing care are handed over, understood and achieved.

- Medical staff writing discharge summaries recalled no specific education on the writing of user-centred and safe discharge correspondence during undergraduate and postgraduate education.

- The availability of discharge correspondence in different systems, for example shared care records, varies across the country with limited opportunities for primary and community care staff to access it via other routes if correspondence has not arrived.

- Patients do not always receive a copy of their discharge summary which removes this ‘backup’ option for providers to access information. It also means patients do not have information to support their own understanding of their care needs.

HSSIB makes the following safety recommendations

Safety recommendation R/2025/065:

HSSIB recommends that the NHS England/Department of Health and Social Care, in collaboration with relevant national bodies including the Professional Record Standards Body, adopts user-centred design principles to develop and validate new discharge correspondence templates for primary and community care settings. This is to provide standards for discharge correspondence that support recipients’ access to high-quality safety-critical clinical information, and that can be contextualised to local system needs.

Safety recommendation R/2025/066:

HSSIB recommends that the Department of Health and Social Care, through its future strategic and policy programmes, sets specific expectations for NHS healthcare providers to ensure that:

- high-quality safety-critical information about patients is accessible after discharge, and

- processes exist to complete safety-critical actions for ongoing patient care within required timeframes.

This is to enable providers to deliver continuity in patient care after discharge from hospital.

HSSIB makes the following safety observation

Safety observation O/2025/074:

Primary, community and secondary healthcare providers can improve patient safety by working collaboratively to recognise and mitigate local system challenges and constraints that prevent the:

- communication of high-quality safety-critical information about patients

- completion of actions for ongoing patient care within required timeframes.

HSSIB suggests safety learning for Integrated Care Boards

Safety learning for Integrated Care Boards ICB/2025/013:

HSSIB suggests that integrated care boards support collaboration between primary, community and secondary care providers across their local systems to:

- jointly validate the quality of discharge correspondence

- plan for the constraints and challenges faced by different parts of their local systems

- assure themselves that risks to patient safety on discharge from hospital are mitigated as far as is practicable.

Local-level learning prompts

HSSIB investigations include local-level learning where this may help providers/organisations and staff to identify and think about how to respond to specific patient safety concerns at the local level. HSSIB has identified learning to help consider and mitigate risks around creating, sending and processing discharge correspondence.

For providers creating and sending discharge correspondence

- How does your organisation ensure staff recognise discharge correspondence as safety-critical information for the clinical handover of care?

- Do your staff know who are the recipients of and users of your discharge correspondence, particularly discharge summaries?

- How does your organisation know that its correspondence meets the needs of those receiving and acting on the information?

- How does your organisation ensure important information about medication changes are reliably and accurately described in discharge correspondence?

- How does your organisation support staff to ensure the contents of discharge correspondence meets the needs of all likely recipients and is of high quality?

- How does your organisation know that all required discharge correspondence is reliably produced, sent and received by all necessary recipients, not just GPs?

- How does your organisation ensure patients and their families/carers (if appropriate) are given an accessible copy of any discharge correspondence?

- How does your organisation ensure discharge correspondence is updated if a patient has further clinical input after the correspondence was written?

- Do your staff recognise that capacity and resource issues in primary and community care mean time-critical actions after discharge may be delayed or unable to be actioned?

- How does your organisation support staff to communicate time-critical actions to providers of ongoing care so they are undertaken within the required time?

- Does your organisation have pathways for primary and community care to troubleshoot incomplete or ambiguous information in discharge correspondence?

- How does your organisation involve staff in the development and testing of EPR templates to ensure they are easy to use and do not contribute to incidents?

- Does your organisation include digital and clinical input in the training of staff to write discharge correspondence to help them understand what ‘good’ looks like?

For providers receiving and processing discharge correspondence

- Does your organisation have processes for identifying and prioritising safety and time-critical actions requested by secondary care?

- How does your organisation manage seemingly ‘duplicate’ correspondence to ensure it is not an updated version with further information or actions?

- Does your organisation have processes for effectively feeding back concerns and incidents to secondary care when discharge communications do not meet your needs?

- How does your organisation involve staff in the development and testing of software and processes to ensure they are easy to use and do not contribute to incidents?

- How does your organisation assure your internal processes for the administration of correspondence to ensure thoroughness of review while looking to be efficient?

1. Background and context

This investigation focused on how communication of critical clinical information influences the safety of patients following discharge from NHS acute hospital (secondary care) inpatient settings when they require ongoing care from primary care services (for example general practice and pharmacy) and/or community care services (for example community nursing).

This section provides background information about the process of discharging patients from hospital, how and to whom information about discharge is communicated and the potential risks to patient safety.

1.1 Discharge from hospital

1.1.1 Care transitions occur when components of a patient’s care move between different parts of the health and social care system. Transitions are necessary to ensure patients receive care in the most appropriate place, from those with the most appropriate knowledge and skills. However, patients are also vulnerable during care transitions (World Health Organization, 2016) and HSSIB has investigated patient safety issues during transitions across several different healthcare settings (Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch, 2021a; 2022a; 2023a; 2023b; Health Services Safety Investigations Body, 2024).

1.1.2 Discharge from hospital is a common form of care transition. In January 2025, for example, there were 301,412 discharges from acute hospitals (NHS England, 2025a). Planning for discharge should start on a patient’s admission to minimise later delays and to ensure care is available once the patient leaves hospital (Department of Health and Social Care, 2024).

1.1.3 In most cases patients will be discharged to their usual place of residence, sometimes with additional support. There are four NHS discharge pathways as shown in table 1. Discharge of patients who have few or no ongoing care requirements may be termed ‘simple’ discharges or ‘Pathway (P) 0’. There were 254,092 P0 discharges (84% of the total) in January 2025 (NHS England, 2025a). Discharge of patients who need more specialised care may be termed ‘complex’ discharges. Acute hospitals have access to ‘care transfer hubs’ which bring together professionals from across health and social care to coordinate discharge for people discharged via Pathways 1, 2 and 3.

Table 1 NHS discharge pathways (Department of Health and Social Care, 2024)

| Pathway | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Discharge to usual place of residence or temporary accommodation co-ordinated by a ward without involvement of a care transfer hub (where a multidisciplinary team supports co-ordination of a patient’s discharge). Includes where no new or additional health and/or social care is required. |

| 1 | Discharge to usual place of residence or temporary accommodation with health and/or social care co-ordinated by a care transfer hub. Includes restarting of a home care package at the same level as before that has elapsed. |

| 2 | Discharge co-ordinated through a care transfer hub to a community bedded setting with dedicated health and/or social care. Includes discharge to intermediate care for rehabilitation, reablement and recovery. |

| 3 | In rare circumstances, for patients with the highest level of complex needs, discharge to a care home placement co-ordinated through a care transfer hub. |

1.2 Communication at discharge

1.2.1 Hospitals are contractually required to issue communications to GPs and other providers of ongoing care when a patient is discharged. The NHS Standard Contract is mandated for use by commissioners for all contracts with healthcare services other than primary care (NHS England, 2025b). The 2025/26 Contract states that:

- ‘The Provider and each Commissioner must use its best efforts to support safe, prompt discharge from hospital and to avoid circumstances and transfers and/or discharges likely to lead to emergency readmissions or recommencement of care.’

- ‘When transferring or discharging a Service User [patient] from an inpatient or day case or accident and emergency Service, the Provider must within 24 hours following that transfer or discharge issue a Discharge Summary to the Service User’s GP and/or Referrer and to any relevant third party provider of health or social care …’

1.2.2 The ‘discharge summary’ (sometimes referred to as a ‘letter’) is the main form of communication that accompanies a patient on their discharge from hospital to support their ongoing care. Communications may also include other forms of correspondence, such as referral or transfer letters to providers of community and other care. Correspondence is sent in various ways, including on paper and electronically, depending on the processes in place between providers. There are national expectations for inpatient discharge summaries to be sent using specific IT programming to support interoperability between different IT systems and services (NHS Digital, 2022).

Discharge summary

1.2.3 The discharge summary provides information about the patient, their recent care and ongoing needs. The Professional Record Standards Body (PRSB) (2019) – a UK-wide body that develops health and care standards – has published an eDischarge Summary Standard which lists mandated, required and optional information that should be included in a discharge summary, such as:

- reasons for admission, diagnoses and the course of care

- investigation results, medications changes (see figure 1) and allergies

- plans and requested actions for healthcare professionals (see figure 1).

The Standard is endorsed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015) as complementary to its own guidance.

1.2.4 The PRSB’s eDischarge Summary Standard is for ‘electronic’ discharge summaries – that is, for summaries that are generated and sent electronically – for patients who are discharged from hospital after any inpatient stay, including day cases. A separate PRSB (2023) Emergency Care Discharge Standard is also available. PRSB describes expectations that a hospital’s electronic patient record (EPR) should generate much of the information in summaries.

1.3 Risks to patient safety at discharge

1.3.1 Patients may be harmed if their discharge is not appropriately planned and/or is not timely. Delayed discharges mean patients remain at risk of developing problems associated with being in hospital and they also reduce inpatient bed availability, affecting the ability of hospitals to admit patients (Health Services Safety Investigations Body, 2023a).

1.3.2 Patients may also come to harm, including by being readmitted to hospital (National Audit Office, 2018), if they are discharged from hospital too soon or if they are discharged without appropriate care arrangements being in place. Ongoing care arrangements include ensuring patients have the necessary medication and equipment on discharge, care is in place and any follow-up actions – such as changes to medications, prescriptions or referrals – are requested.

1.3.3 Supporting the safety of patients at discharge and their ongoing care requires discharging hospitals to create and send correct and timely correspondence. Where this does not occur, the limitations in communication may result in patient harm from the side effects of medications, a lack of prescribed medications, gaps in ongoing care or equipment provision, worsening of health problems, or delayed and/or missed diagnoses. Incident reports highlight examples where patients have died following delayed or missed care contributed to by limitations in the communication of critical clinical information on discharge from hospital.

Figure 1 Example part of an eDischarge summary from the Professional Record Standards Body (2019)

2. Analysis and findings – perspectives from care providers

This section describes the investigation’s findings following engagement with care providers, patients and their families. The approach taken by the investigation, its terms of reference and a summary of the evidence are described in the appendix. The investigation focused on incidents where a patient had been discharged from an acute hospital inpatient setting to their usual place of residence and needed ongoing care from providers of primary (for example, general practice and pharmacy) and/or community (for example, nursing) care. Stakeholders described perceptions that these transitions were some of the “greatest risks” to patient safety.

The investigation considered the transfer of ‘critical clinical information’ (referred to as ‘the information’) when a patient was discharged from hospital. Critical clinical information was defined by the investigation as ‘the information required for the correct and timely ongoing care of the patient’. The investigation identified issues in relation to:

- preparation and quality of the information

- sending the information

- receipt and processing of the information

- access to and redundancy of the information.

2.1 Impact of patient safety incidents

2.1.1 The impact of incidents where information about patients was not effectively communicated between providers of care was demonstrated through the investigation’s meetings with people who had been harmed. Patients and their families shared experiences of physical and psychological harm that had resulted from clinical information not flowing “seamlessly” between providers. Family members described the “devastating” impact, “suffering” and “ongoing trauma” associated with these experiences that this report is unable to fully reflect.

2.1.2 The incidents shared included where patients had not received care that they required. This had resulted in some family members having to “battle” to access that care which prevented them from spending quality time with their loved ones in their last weeks. Having to take “responsibility” for ensuring the right information about their loved ones got to the right place was a recurrent issue highlighted by families, with feelings of being “on their own” without support from healthcare organisations.

2.1.3 Where people had come to harm, several patients and families described feeling that their experiences were unheard by organisations and actions had not been taken to improve care; they therefore felt their “suffering means nothing”. One family member specifically described the “psychological damage” caused by the events affecting their loved one that would remain with them and which was further compounded by the response from the organisations following their raising of concerns.

2.1.4 Staff across primary and community care also described the impact that incidents had had on them. These included responses representative of ‘moral injury’ (Williamson et al, 2021) – where harm occurs to a person after being exposed to events that conflict with their own values and beliefs – when involved in incidents acting on limited information about patients. They described being placed in difficult situations and having to make decisions for which there was a potential to be blamed. They also described how chasing incomplete or missing information was time consuming, stressful and not always successful.

2.2 Preparation and quality of the information

2.2.1 Primary and community care staff described that the discharge summary (also referred to as a ‘letter’) was the “key” piece of clinical correspondence about a patient following their discharge. Hospital staff described how summaries were prepared by medical teams (resident doctors, nurse practitioners and physicians associates) and aimed to describe the care provided while the patient was in hospital.

2.2.2 Hospital staff told the investigation that every inpatient “would” have a discharge summary prepared when they left hospital. However, primary and community care staff did not always receive a summary; on exploration it was identified that sometimes the summary was not created (see Vignette A). When not created, hospital staff suggested that this was because of unclear responsibilities for who “should” prepare the summary. Those responsibilities had not always been defined, especially where processes had changed – in Vignette A the patient was discharged by an inpatient specialty but from the emergency department.

Vignette A

A patient who had recently been discharged from hospital was administered insulin by a community nurse. The nurse did not realise that the patient’s insulin regimen had changed during their hospital stay. The patient became unresponsive and needed to be readmitted to hospital.

The hospital identified that no discharge correspondence about the insulin had been produced and there was no discharge summary. The patient had gone to the emergency department (ED) and been admitted under a medical team. The patient remained in the ED and was seen there by a medical team and diabetic nurse specialist. There was no process to ensure that a discharge summary was completed for patients who were in the ED under the care of a medical team.

Summary based on a serious incident investigation

2.2.3 Rather than a discharge summary not being created, staff described that it was more common for its completion to be delayed for more than the 24 hours. This was due to workforce pressures, prioritisation of sick patients and the time it took to summarise care for patients admitted with complex care needs. It was also more common that summaries were received by recipients but that they did not provide the information required. The investigation observed how the information within discharge summaries for providers of ongoing care varied in terms of its quality – that is, its appropriateness, accuracy and completeness. In Vignette B, a lack of complete information contributed to harm.

Vignette B

The patient died of pancreatitis following a stay in hospital where they underwent a bile-duct procedure; pancreatitis is a complication of such procedures. After leaving hospital the patient consulted their GP because of ongoing pain. The GP was unaware of the details of the patient’s hospital admission because the discharge summary did not include information about the bile-duct procedure.

The discharge summary was drafted before the patient’s procedure took place and the information was not updated before they left hospital. When drafting the summary, the software allowed the doctor to ‘mistakenly click on the completed button rather than the save button’.

Summary based on a report to prevent future death

2.2.4 The investigation also saw other discharge correspondence which included information for other providers of ongoing care, such as community nursing teams (CNTs). The investigation heard and again observed how the quality of the information in this correspondence varied. Examples included where correspondence did not include the minimum information needed for ongoing administration of medications to patients in the community. CNTs described how they often also needed a copy of a discharge summary to answer clinical questions that were not answered by the correspondence; CNTs did not always have access to the discharge summary (see 2.3.2).

Appropriateness of discharge information

2.2.5 The term ‘appropriateness’ refers to whether the contents of correspondence included the information needed by recipients who would be providing ongoing care to the patient. GPs and CNTs described instances where information that they needed to inform ongoing care (see Vignette B) was missing. CNTs wanted more information about “what was normal for the patient” at discharge, such as vital sign measurements (for example temperature, blood pressure and heart rate). GPs said that the lack of information in discharge summaries led to questions about whether an “error” had occurred. For example, incomplete medication lists in summaries made GPs question whether a patient’s medications had been stopped or missed.

2.2.6 The investigation asked hospital staff who they understood to be the recipients of a discharge summary. Most saw the GP as the recipient, with limited recognition that it was used by others. Staff described “assuming” what information a GP needed because they had never been told, had never worked in general practice and local guidance did not describe these needs. GPs told the investigation that information about patient “next steps” was found in different places in a summary and therefore was sometimes missed.

2.2.7 Medical staff and hospital digital teams described limited training on writing a “good” discharge summary. Training focused on using the electronic patient record (EPR) and was delivered by digital teams. To support writing discharge summaries, providers described following the Professional Record Standards Body’s (PRSB, see 1.2.4) standard. However, the investigation observed differences in local configurations of discharge summary templates against the standard, and digital teams were unsure whether their templates met the needs of recipients. The investigation also heard mixed views about whether the PRSB-informed templates supported care – some thought they were too “flexible” and unstructured, while others thought they required too much information. GPs thought that templates did not make it clear “up front” what the GP needed to do for the patient following discharge.

2.2.8 The investigation did not explore the accessibility of the contents of discharge summaries for patients as the greater risk was understood to be the communication with providers of ongoing care. However, the investigation saw some summaries for patients that did not support accessibility, such as a printed version provided in “size 7 font”.

Accuracy and completeness of discharge information

2.2.9 The term ‘accuracy’ refers to the correctness of the information in correspondence, and ‘completeness’ to how comprehensive it is. Vignette B gives an example of a discharge summary that was not comprehensive. The investigation also identified incidents where information was written in a way that made it ambiguous. GPs and CNTs described limited opportunities to feed back and clarify problems relating to the accuracy and completeness of summaries to their local hospitals, and when they had, they had seen limited action. In contrast, hospitals described often “not hearing about” problems with discharge summaries from GPs and CNTs.

2.2.10 Hospital staff told the investigation about the timing of the writing of discharge summaries, and how this could impact accuracy and completeness. In short-stay areas, such as acute medical units, summaries were written at the point a patient was discharged. Because of the demand on beds for patients awaiting admission, they were sometimes “rushed” to support the “freeing-up of beds” and certain information, such as medications, was not included unless there had been changes. As described in 2.2.5, this caused confusion.

2.2.11 In long-stay areas, such as surgical wards, staff were encouraged to start the discharge summary when the patient was admitted and then to update it as care progressed. In reality, staff described how updates were not made due to other demands. This meant, at the time of discharge, the summary would be completed by any available staff and they might not know the patient. Staff unfamiliar with a patient had to draw conclusions from sometimes difficult to understand notes and this contributed to inaccurate information.

2.2.12 The investigation observed how EPRs did not always support staff to write discharge summaries. EPRs had limited functionality to automatically import information into summaries and staff were observed searching for information and then typing or ‘cutting and pasting’ it into a summary. This was heard to be inefficient and had led to incorrect transcribing of information or transcribing from the wrong patient’s records. Some information was also outdated where a patient had been seen by a specialist after the summary had been completed.

2.3 Sending the information

2.3.1 GPs described situations where discharge summaries had not been received or had been sent to them “blank”. The investigation identified several incidents where summaries, among other correspondence, had been created but not sent (see Vignette C). Incidents have also been described in the media where correspondence dating back several years had not been sent. The impact of not sending correspondence included missed care and increased workload to “chase” correspondence (Colivicchi, 2024).

Vignette C

Following contact from a GP, a hospital identified several discharge summaries that had not been sent. The issue had been happening for around 1 year. The hospital reviewed all affected summaries and identified several near misses (where a patient had the potential to be harmed) and one incident that had led to harm. The hospital’s investigation identified that the process for ‘sign off’ of discharge summaries on the unit where the incident originated had not been clearly defined, and differed from that on other wards in the hospital.

Summary based on a serious incident investigation

2.3.2 As described in 2.2.4, copies of discharge summaries are also required by other providers of ongoing care. The investigation was told by staff from those providers that they did not automatically receive copies of summaries. From a CNT perspective, the absence of a summary was seen and heard to result in difficulties knowing how best to clinically care for a recently discharged patient, particularly if information in CNT correspondence was limited. The investigation joined CNTs visiting patients and observed the challenges they faced providing care without necessary information (see Vignette D).

Vignette D

The patient was an older woman who lived alone. She had been discharged from hospital the day before and the CNT referral described the need for ‘wound care’. The referral also noted that the patient had been admitted due to a low blood sugar level from a potential accidental overdose of insulin. The CNT visited the patient and noted that she needed help with her insulin.

During the visit, the nurse found no discharge correspondence or prescription. The patient described that her insulin doses had changed in hospital. The nurse accessed the CNT and GP EPRs but found no discharge information. They were unable to access the hospital EPR. As the patient was thought to have capacity (the ability to use and understand information to make a decision), the nurse administered insulin following their instructions. The patient developed a low blood sugar level and had to be readmitted to hospital.

Summary based on a serious incident investigation and observation

Hospital processes

2.3.3 Vignette C demonstrates the manual nature of the hospital’s processes for creating and sending discharge summaries. The investigation identified several incidents where unsent summaries had been the result of tasks not being actioned – for example, not creating a summary (Vignette A) or not ‘clicking complete’ (Vignette B). Contributing factors included unclear processes, a lack of defined responsibilities, and variation in processes across wards in a hospital. Several incidents occurred where new processes had been implemented (Vignette C – opening of a new unit) or processes had changed (Vignette A – inpatient teams seeing patients in the ED).

2.3.4 In several incidents the process issues were not recognised until a recipient had highlighted not receiving a discharge summary. This had led to ‘look backs’ where hospitals had identified multiple cases of unsent correspondence over a period of time, sometimes years. GPs also told the investigation that they were aware of several occasions where summaries had not been received but they had not always informed the hospital. Reasons for not doing so included the time required to chase correspondence when services were already under pressure, unclear or absent routes by which to contact or inform secondary care, and because on past occasions informing a hospital had not led to any changes in practice or resolution of the problem.

2.3.5 Hospital staff told the investigation that the EPRs they used did not support them to know whether a discharge summary had been sent; they therefore “assumed” it had gone. Where hospitals recognised this risk, some had implemented manual checks that all summaries had been sent for patients discharged the previous day. Some EPRs had also been configured to highlight summaries that had not been completed/sent and intelligence reports had been set to summarise outstanding correspondence.

2.3.6 During observations the investigation also noted variability in whether patients were given a copy of their discharge summary. GPs told the investigation that this was an important “backup” if they (the GP) had not received the summary; the investigation saw the reality of this on several occasions. On several wards visited, staff described that they would “usually” give a copy of the summary to the patient. However, some also thought it was unnecessary for the patient to receive a copy as they assumed their GP would receive one.

Technical factors

2.3.7 The investigation saw few incidents that had resulted from issues with IT systems not working as intended. A small number were identified where technical issues contributed to correspondence not being sent. In some incidents the specifics of the technical issues were not clear and were described as ‘glitches’ (Colivicchi, 2024). Other incidents were due to factors such as IT system configuration/maintenance issues, inadvertent disabling of functionality, unexpected downtime, hardware failure and cyberattack.

2.3.8 The investigation noted that several incidents occurred at the time of local configuration, maintenance or upgrading of IT systems. The investigation did not examine digital change processes and governance but heard that the “robustness” of these processes could vary; similar was found in a previous investigation (Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch, 2022b) into the implementation of a prescribing system.

2.3.9 In most incidents seen by the investigation, IT systems worked as configured and were rarely considered by local investigations as contributing to incidents. The investigation noted that the way software had been configured and its functionality led to a reliance on staff to manually complete tasks to ensure discharge summaries were sent. The IT systems did not always support users to undertake required tasks and created conditions where errors could occur.

2.3.10 One digital team also demonstrated how their EPR software could create duplicate and blank discharge summaries. Under certain conditions, clicking ‘complete’ resulted in a summary automatically being sent to the GP. If it was clicked inadvertently or before completion, it would send a blank or incomplete summary. If repeatedly clicked it would send duplicate copies. Local teams described needing this functionality to allow updated summaries to be sent.

2.3.11 The investigation also explored why discharge summaries may not be sent to care providers who need them, such as CNTs, allied health professionals and social care providers. Some digital teams were not aware of this requirement and others described limited IT functionality to send correspondence to multiple recipients. There was limited awareness among clinical staff and digital teams of the challenges faced by CNTs when attempting to access summaries. In several hospitals, sending summaries to recipients other than the GP meant putting paper copies in the post. Clinical staff described “assuming” that summaries were automatically sent to “everyone”.

Risks of ‘simple’ discharges

2.3.12 The investigation noted that several incidents where CNTs had not received quality discharge correspondence occurred following brief patient admissions. In these incidents there had been a change to the patient’s long-term medications (Vignettes A, D and E involved insulin) but CNTs described arriving at patients’ homes not knowing what dose of medication to administer and what changes had been made in hospital.

2.3.13 CNTs told the investigation that discharges for patients after brief admissions were seen as “simple” (Pathway 0 – see 1.1.3) because patients would return to their usual residence with, if required, their usual care in place. CNTs therefore thought the quality of correspondence was poorer because hospital staff might assume it was not needed. In contrast, CNTs described better correspondence for patients who required significant changes to ongoing care and whose discharge was facilitated by care transfer hubs.

2.4 Receipt and processing of the information

2.4.1 The investigation observed the management of clinical correspondence by general practices and providers of community care. Discharge correspondence, including summaries and transfer of care forms, were often received electronically. Large volumes of paper-based correspondence were also seen in general practices which included posted discharge summaries.

2.4.2 Staff across providers told the investigation about issues with the receipt and processing of correspondence. The investigation identified incidents where discharge correspondence had not been processed or where there had been delays, and where correspondence had not been processed as intended. In Vignette E repeated copies of correspondence had not been processed.

Vignette E

When the patient was discharged from hospital a referral letter and copy of the discharge summary were sent to a community care provider for wound care. Four days after discharge the patient was found unwell and had to be readmitted to hospital, where they were diagnosed with a life-threatening complication of diabetes.

A local investigation found that the community care provider had received two additional referral letters for the patient, both requesting the administration of insulin. The patient had diabetes and had not been receiving insulin while an inpatient, but it was to be restarted after discharge. The first referral letter and discharge summary included no mention of insulin. The two further referrals were not processed.

Summary based on a serious incident investigation

Volume of incoming correspondence

2.4.3 The investigation saw the volume of correspondence received by general practices and that it was contributed to by blank, duplicate and updated correspondence. Due to the volume, and the capacity of administrative teams, it was sometimes “weeks” before correspondence was processed and ongoing actions identified. Hospital staff were generally unaware of these potential delays when requesting actions in discharge summaries.

2.4.4 Due to the volume of correspondence, staff in providers of ongoing care had developed “efficient” ways to process workloads. Staff described looking for specific fields for key information. They recognised that this made them less thorough and that, due to variation in how summaries were created (see 2.2.6), information may not be where they expected. Workforce challenges, with sickness and burnout among clinical and non-clinical staff, contributed to the need for efficiency.

In-hospital processes

2.4.5 As described in 2.4.3, the investigation identified that multiple copies/versions of correspondence for the same patient were often sent to providers of ongoing care. Hospital staff described that it was necessary to update correspondence if information was missing or had changed. Due to demand on hospital beds, the investigation also saw where specialty reviews of patients had been undertaken after they had been ‘discharged from the electronic system’ but had not left the hospital. This created capacity, but risked impacting on the patients’ later care (see Vignette E).

2.4.6 Similar to the assumptions described about the timeliness of actions by recipients (see 2.4.3), several hospital staff described expectations that recipients would review and process any new version of correspondence. As Vignette E highlights, this expectation was not always met and local decisions to not process additional correspondence were influenced by the volume received and because they were “often” assumed to be duplicates (see 2.3.10).

2.4.7 GPs and CNTs told the investigation that, if there had been critical changes in information that affected a patient’s ongoing care, this needed explicit communication. Updated versions of correspondence alone were not considered reliable. A small number of experienced hospital staff described telephoning recipients if there had been critical changes.

2.4.8 The investigation also heard that EPRs did not always facilitate users to identify whether further correspondence was a duplicate or new version. Hospital and recipient EPR users described systems as “cluttered” and that relevant information was not easy to access; similar has been found in other HSSIB (2023a) investigations.

Manual processing and EPRs

2.4.9 The need to “manually process” correspondence influenced the timeliness and accuracy of information management. In all providers, no matter their digital maturity, staff had to undertake manual tasks to process information. Manual tasks resulted in missed, delayed or incorrect care, such as where correspondence asking for a follow-up to investigate cancer was inadvertently ‘marked’ as ‘no further action’ required.

2.4.10 The investigation observed the manual processing of correspondence using different IT systems in general practices. In some, the same software managed correspondence and provided the practice’s EPR. In others the EPR and correspondence systems were separate. Across the software, staff described issues with usability including cluttered interfaces, no alerting of whether correspondence included critical information, and it being easy to choose a wrong action. A repeated concern was a lack of visibility to help mitigate the “unknown risk” in unprocessed correspondence.

2.4.11 The way different software packages handled information also varied. Some were more able than others to transfer received information directly into an EPR or highlight it. However, several staff described not trusting this functionality and that information required manual checking. They felt the nuanced nature of clinical information and the varying quality of the information sent meant the software’s functionality could not be relied upon.

2.4.12 Digital teams for general practices and providers of community care also described a lack of “structure” to correspondence that created a barrier to “interoperability” between IT systems. For example, there was no standardised layout of information and inconsistent use of clinical terms. SNOMED Clinical Terms (CT) (a structured clinical vocabulary that provides a single shared language for use in electronic systems) is mandated for use by NHS healthcare providers in England in EPRs (NHS England, 2024a). All general practices visited by the investigation used SNOMED CT, but not all the hospitals visited did. Where it was not used, the provider’s digital team said this was because they were awaiting system updates and needed to manage competing priorities. They also described that, even if SNOMED CT was used, the discharge summary was sent as a PDF which removed the potential for interoperability.

2.5 Access to and redundancy of the information

2.5.1 The investigation also examined how general practice staff and CNTs accessed information when they did not have immediate access to discharge correspondence. This included exploring where else clinical information was stored or duplicated – ‘redundancy’ refers to the intentional duplication of critical information to ensure it is reliably accessible.

2.5.2 When discharge summaries were not immediately available, but were needed, staff contacted the hospital, asked the patient, and/or attempted to access the information through other electronic portals. An “over reliance” on patients and families was described and staff recognised risks with using verbal information from patients (see Vignette D). However, they also described having limited options and needing to balance the risk of inaccurate information against a patient going without time-critical care.

2.5.3 The investigation saw variation in whether staff from one provider were able to access the EPR of another provider. Examples of access included direct links between EPRs and remote logins. The use of direct links was heard to be beneficial as it made patient information easy to access and supported continuity in care. Remote logins sometimes required extra hardware and the “remembering” of login details which were barriers to use.

2.5.4 Multiple examples were also heard where linking of EPRs or the creation of remote access had not been achieved. Some of these were for technical reasons – for example, one provider of community care used the same EPR as most of the local general practices but because of different ‘instances’ (versions) the EPRs could not be linked. In several cases, non-technical barriers had prevented linking, including information governance concerns, lack of finances to fund projects and infrastructure, and limited co-operation between providers.

2.5.5 Staff also described their use of ‘shared care records’ which bring together separate records from different health and care organisations into one place (NHS England, 2023). Each integrated care system (ICS) has a shared care record and the investigation saw these across the different areas visited. The records varied in terms of which providers, including social care, contributed information, the availability of information and the degree of IT system maturity.

2.5.6 Staff across different providers were positive about shared care records because they provided an alternative route to access information such as discharge summaries. Some GPs and CNTs described not using shared care records due to a lack of information in them, difficulties ‘surfacing’ the information they needed, and because of a lack of trust – in one example, a CNT had stopped using the record because test results had been linked to the wrong patients.

2.5.7 When viewing shared care records the investigation looked to see if they contained the information GPs and CNTs wanted. Not all contained discharge summaries and/or other discharge correspondence. Staff said this was due to providers not contributing information for reasons such as the provider’s digital maturity and data sharing concerns. Invariably, inpatient clinical notes and medication charts were not visible. Hospital digital teams and shared care record teams described reservations about sharing medication charts due to concerns that the information visible may not be the most recent.

2.6 Summary

2.6.1 Through engagement with providers the investigation found risks associated with the communication of critical clinical information on discharge of patients from acute hospital inpatient settings, with the following contributory factors:

- the design and configuration of IT systems involved in the creation, sending and processing of information between providers

- supporting conditions across providers to enable timely creation, sending and processing of high-quality information

- collaboration between providers to ensure discharge correspondence meets the needs of recipients and discharge processes meet the needs of patients.

2.6.2 During the investigation’s activities staff repeatedly described that the risks to patient safety were due to a lack of IT systems “talking to each other”. While the investigation identified issues with interoperability between IT systems, wider issues with ‘integration’ across providers were also found to influence collaboration and learning between providers. Findings are considered further in section 3 from regional and national perspectives.

Local-level learning prompts

HSSIB investigations include local-level learning where this may help providers/organisations and staff to identify and think about how to respond to specific patient safety concerns at the local level. HSSIB has identified learning to help consider and mitigate risks around creating, sending and processing discharge correspondence.

For providers creating and sending discharge correspondence

- How does your organisation ensure staff recognise discharge correspondence as safety-critical information for the clinical handover of care?

- Do your staff know who are the recipients of and users of your discharge correspondence, particularly discharge summaries?

- How does your organisation know that its correspondence meets the needs of those receiving and acting on the information?

- How does your organisation ensure important information about medication changes are reliably and accurately described in discharge correspondence?

- How does your organisation support staff to ensure the contents of discharge correspondence meets the needs of all likely recipients and is of high quality?

- How does your organisation know that all required discharge correspondence is reliably produced, sent and received by all necessary recipients, not just GPs?

- How does your organisation ensure patients and their families/carers (if appropriate) are given an accessible copy of any discharge correspondence?

- How does your organisation ensure discharge correspondence is updated if a patient has further clinical input after the correspondence was written?

- Do your staff recognise that capacity and resource issues in primary and community care mean time-critical actions after discharge may be delayed or unable to be actioned?

- How does your organisation support staff to communicate time-critical actions to providers of ongoing care so they are undertaken within the required time?

- Does your organisation have pathways for primary and community care to troubleshoot incomplete or ambiguous information in discharge correspondence?

- How does your organisation involve staff in the development and testing of EPR templates to ensure they are easy to use and do not contribute to incidents?

- Does your organisation include digital and clinical input in the training of staff to write discharge correspondence to help them understand what ‘good’ looks like?

For providers receiving and processing discharge correspondence

- Does your organisation have processes for identifying and prioritising safety and time-critical actions requested by secondary care?

- How does your organisation manage seemingly ‘duplicate’ correspondence to ensure it is not an updated version with further information or actions?

- Does your organisation have processes for effectively feeding back concerns and incidents to secondary care when discharge communications do not meet your needs?

- How does your organisation involve staff in the development and testing of software and processes to ensure they are easy to use and do not contribute to incidents?

- How does your organisation assure your internal processes for the administration of correspondence to ensure thoroughness of review while looking to be efficient?

3. Analysis and findings – perspectives from regional and national organisations

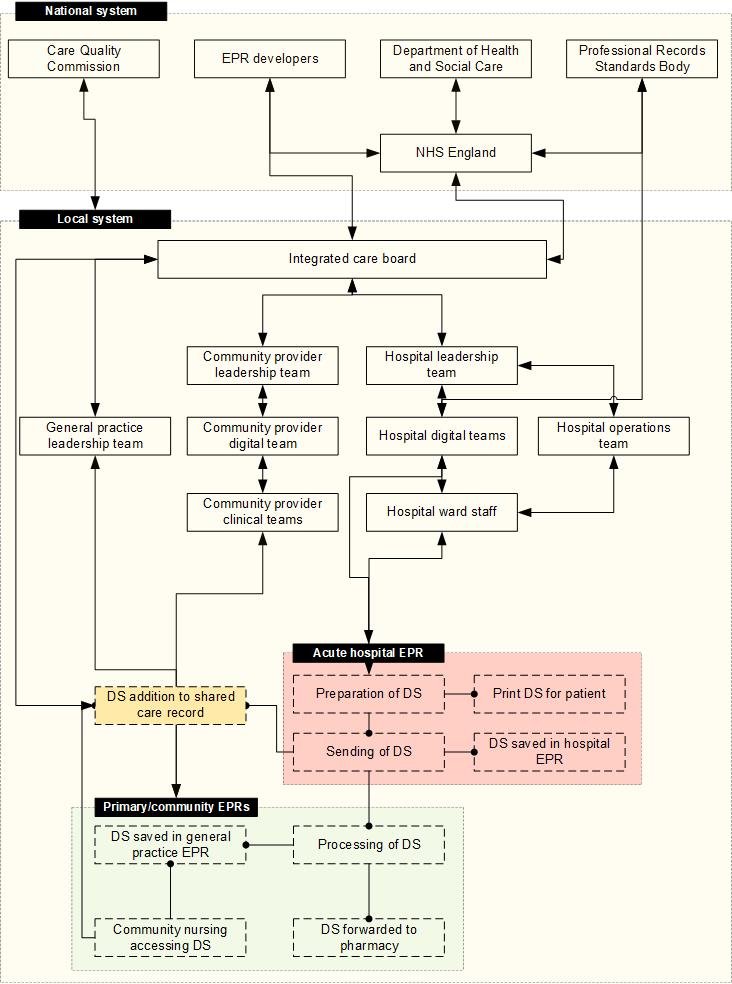

This section describes the investigation’s findings following engagement with regional and national organisations. It also includes insights from ‘digitally mature’ providers around how they have mitigated some of the patient safety risks identified in section 2. Findings have been grouped under the following themes relating to critical clinical information (the ‘information’) when a patient is discharged from an acute hospital inpatient setting:

- accountability and oversight

- integration and discharge communications

- interoperability of digital systems.

3.1 Accountability and oversight

3.1.1 Improving discharge is a national priority (Department of Health and Social Care, 2024) and must be accompanied by information and planning that supports a patient’s ongoing care. The benefits of high-quality discharge correspondence are clearly described (for example, Scarfield et al, 2022; Schwarz et al, 2019). The investigation identified that high-quality information is not always available at discharge.

3.1.2 Everyone the investigation engaged with recognised the risks it had found around discharge information. Issues with the creation and processing of correspondence were described as “significant”, “long lasting” and “unresolved”. Several stakeholders described the associated risks as “normalised” and under-appreciated.

3.1.3 The investigation commonly heard that pressures on healthcare meant discharge improvement work often focused on patient flow and the speed of discharge with limited consideration of the quality of information in correspondence. The investigation did note that discharge communications were highlighted as a safety focus in around a third of hospital patient safety incident response plans (from a review of 114 plans in January 2025). However, in practice, the investigation found limited examples of improvement work focused on the communication component.

3.1.4 Some stakeholders also described that the quality of discharge information had “never” been a focus. A “fundamental cultural issue” was described that:

- does not appreciate that discharge correspondence is “safety critical”, and

- relinquishes accountability for a patient when they leave hospital.

Factors that contributed to normalisation of the risks associated with patient discharge included a lack of visibility in secondary care of the consequences of poor-quality information, a national focus on flow, unclear accountabilities, and conflicting views about the responsibilities of secondary and primary care. A ‘them and us’ culture between secondary and primary care has also been described (Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, 2023).

Accountability for patient safety

3.1.5 Accountability is the ‘obligation to … take responsibility for the safety performance in accordance with agreed expectations’ (SKYbrary, 2021). The investigation heard about “conflict” between primary and secondary care around who is “accountable” for a patient’s care and safety after discharge. Some secondary care stakeholders described that, once the patient had left hospital, accountability passed to the GP. Primary care stakeholders challenged that they could not be accountable for the patient without clear and comprehensive correspondence, and that discharging providers needed to ensure a patient is safe until primary/community care has the capacity to take on their care (this is considered further in 3.2).

3.1.6 The investigation searched for described expectations for accountability for patient safety on discharge and for the quality of discharge correspondence; no specific descriptions were found. The Department of Health and Social Care (2022a; 2024) does refer to the importance of ‘safe and timely’ discharge and that joint accountability ‘leads to better outcomes’; guidance also links to ‘action cards’ to support hospital discharge but there is no explicit reference to accountability or description of what it looks like in practice and how it should be achieved. The NHS Standard Contract (2025b) and NHS England (2024b) Standard General Medical Services Contract also do not refer to accountabilities in relation to discharge.

3.1.7 When exploring safety accountability, views varied as to whether individual providers or people were accountable, or the integrated care board (ICB). Stakeholders described that accountabilities needed to be clearly defined, with collaboration between providers to ensure processes – such as the creation and sending of discharge correspondence – support patient safety. It was also heard that traditional views on accountability needed to change as healthcare has evolved. Capacity and resource limitations meant it was not always possible for providers who have traditionally delivered aspects of care after discharge to continue to do so. For example, capacity in general practice means it may not be possible to follow-up with a patient within 48 hours of discharge (this is considered further in 3.2.22).

3.1.8 Some stakeholders suggested that ICBs should be accountable for cross-organisational risks to patient safety, such as those associated with discharge. The investigation engaged with several ICBs and was told that their role was “facilitating” conversations between primary and secondary care to improve “integration”, rather than being accountable. ICBs further described a role “overseeing” the safety and quality of services.

3.1.9 This investigation found no clear accountability for the safety of patients during discharge. This finding echoes HSSIB’s (2023b; 2025a) previous work exploring safety management which found no multi-level accountability framework that specifies who should be responsible for managing patient safety risks. The finding also supports previous HSSIB (2024; 2025a; 2025b) safety recommendations relating to accountability, for example:

‘HSSIB recommends that the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care directs and oversees the identification and development of a patient safety responsibilities and accountabilities strategy related to health and social care integration. This is to support the management of patient safety risks and issues that span integrated care systems.’ (Health Services Safety Investigations Body, 2025b)

3.1.10 From a provider perspective, the investigation heard agreement that accountability for patient care transitions from the hospital to other care providers and the patient’s GP on discharge. However, there was not agreement on:

- when that point of transition occurs, or

- what critical clinical information is required for that handover.

These findings are considered further in 3.2 and have contributed to the safety recommendation in 3.2.29.

Oversight of patient safety

3.1.11 The term ‘oversight’ refers to ‘the ongoing monitoring of performance and quality of services being delivered by the NHS’ (NHS England, 2024c). Similar to the findings of HSSIB’s (2025a) work exploring safety management, this investigation found differences between what was expected of ICBs when overseeing and managing cross-organisational risks and what was done in practice. Contributing factors included limited clarity on what oversight looks like, limited resources to achieve expectations, the need to balance competing priorities, and limited transparency of safety issues.

3.1.12 Specific to discharge, several ICBs described how their oversight was focused on “performance” rather than patient outcomes. They were guided by NHS England’s (2022; 2024c) ‘oversight metrics’, such as ‘proportion of people discharged from hospital to their place of residence’. The investigation did not identify active monitoring or interventions related to discharge summaries as set out in the NHS Standard Contract (see 1.2). Some ICBs were involved in discharge improvement work but described needing to focus on what they perceived was required nationally in relation to performance. They therefore had limited resource to consider patient-related risks, including those from correspondence.

3.1.13 The investigation was told by some ICBs and providers that, because they had not heard about problems with discharge processes and the quality of correspondence, they “assumed” safety was maintained. However, they also described not having adequate oversight of incidents and had concerns about the maturity of information in the Learn from Patient Safety Events service; similar has been heard by other HSSIB (2025a) investigations. Several ICBs were relying on other processes and feedback mechanisms to hear about safety issues from providers.

3.1.14 From a provider perspective, oversight of discharge correspondence commonly involved staff manually monitoring and reviewing whether discharge summaries had been sent. Few providers actively sent summaries to community nursing teams (CNTs) or other community allied health providers, and so monitoring focused on sending to GPs. In several providers, monitoring mechanisms had not existed until an incident had occurred (see 3.2); in others, mechanisms did not exist at all. In more digitally mature hospitals, digital interfaces with general practice had been configured to highlight where a summary had not been received into a practice’s EPR.

3.1.15 The investigation found limited oversight of discharge processes beyond process metrics for performance, and limited consideration of the quality of the information in discharge correspondence and its influence on patient outcomes. Contributing factors included national direction to focus on process measures rather than also considering patient outcomes, immaturity of some data systems, and normalisation and under-appreciation of the safety risks. ICBs told the investigation of potential benefit in reviewing national metrics to focus on whether a patient receives the ongoing care they require within an expected timeframe, rather than whether correspondence (with its variable content) has been sent within a timeframe. This finding informed the safety recommendation in 3.2.29 and contributed to the local learning in 2.6.

Regulatory oversight of discharge processes

3.1.16 The investigation engaged with the Care Quality Commission (CQC) and was told that its inspections consider the patient expectation that ‘When I move between services … there is a plan for what happens next and who will do what…’ (Care Quality Commission, 2025a). However, CQC also described challenges scrutinising cross-provider pathways, such as discharge, due to its approach being focused on individual providers.

3.1.17 HSSIB has previously recommended that the CQC scrutinises pathways between providers through its responsibilities to assess integrated care systems (ICSs) – HSSIB’s safety recommendations have focused on surgical pathways and transitions in mental health (Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch, 2021b; Health Services Safety Investigations Body, 2024). The CQC had developed a proposed methodology for ICS assessments and confirmed that it would enable focus on cross-provider pathways. However, implementation is “on hold” due to the withdrawal of the Department of Health and Social Care’s request for the proposal (Care Quality Commission, 2025b). This therefore means there continues to be limited oversight at a regulatory level of transitions and pathways of care between providers and across local health and care systems (local systems).

3.2 Integration and discharge communications

3.2.1 The investigation repeatedly heard that discharge processes were not “integrated” or “joined up”. This was demonstrated by:

- a lack of collaborative working to ensure correspondence meets the needs of all recipient providers, and

- a lack of sharing and joint plans for mitigating the challenges different providers face caring for patients after discharge.

The investigation observed how integration requires collaboration, agreement on responsibilities, recognition of constraints (restrictions/challenges) across local systems, and a supportive infrastructure.

3.2.2 Legislation describes the requirement for co-operation between bodies to support and advance the health and welfare of people (National Health Service Act 2006). The Department of Health and Social Care (2024) statutory guidance also states the requirement that co-operation is considered within ICSs ‘to ensure that discharge processes and services are integrated across local areas where possible’.

Clinical-facing correspondence

3.2.3 The discharge summary was described by staff as the “key” piece of clinical discharge correspondence, as “a clinical handover” and as “safety critical”. The requirements for a discharge summary are described in the NHS Standard Contract (NHS England, 2025b) and the Department of Health and Social Care (2022a) describes that medical staff are responsible for ensuring ‘e-discharge summaries shared with GPs contain pertinent information from the hospital episode’. In support, the Professional Record Standards Body (PRSB) standard (see 1.2.3) is available and all summaries seen by the investigation aligned with the template in the standard.

3.2.4 The investigation considered whether discharge summary templates met the needs of various users (see 2.2.7). GPs described the need for templates to provide clarity on the key actions required of them – several described that they “do not read the whole summary” and just needed to know “what you want me to do”. CNTs also described no national standard for ‘district nursing referrals’ to support consistency in information. The investigation saw multiple local CNT referral templates which varied in their content. One of these had been developed through collaboration between CNTs and the local hospital provider; this template was structured and captured details requested by CNTs, including vital signs on discharge (in contrast to the communications described in 2.2.5).

3.2.5 The investigation met with the PRSB to understand its role and how its standards are commissioned. The PRSB has not produced a standard for ‘district nursing referrals’ because one has not been nationally commissioned. Regarding the eDischarge Summary Standard, the PRSB described its function is to provide information for a patient’s GP as this is what it was commissioned for. PRSB were aware of variation in the implementation of the standard in hospital EPRs and described this to be the responsibility of providers; the PRSB further described “limited oversight” of the quality of implementation of the standard across the NHS.

3.2.6 The PRSB recognised that the eDischarge Summary Standard was due for “uplift and renewal”. It described how the way general practice receives and processes correspondence has changed and this needs “recognising” – for example, correspondence is now commonly processed by administrators and a GP may never see the summary. The PRSB told the investigation that standard design of discharge correspondence/summary for wider than general practice would require specific commissioning, consultation and user involvement.

3.2.7 The investigation met with NHS England to explore its work in support of improving the quality of discharge correspondence. NHS England described barriers to effective communication on discharge, such as limited clarity on the role and purpose of communications, their structure and how they are digitally sent. In response, it was looking to undertake future work to improve interoperability (see 3.3) and discussed the benefits of structured multidisciplinary correspondence for different healthcare professionals and providers of ongoing care. At the time of writing, the timeframes and future of this work were unknown.

3.2.8 The investigation found variability in the contents and quality of discharge correspondence, most notably discharge summaries, with evidence that they did not always meet the needs of recipients. It was evident to the investigation that processes for discharge and the communication needs of providers have evolved, but the types and content of correspondence have not evolved alongside to meet these needs. PRSB standards provide a route via which the design and quality of correspondence can be influenced and potential future work by NHS England may mitigate some of the risks with discharge correspondence found by this investigation.

3.2.9 The investigation’s findings highlight the importance of identifying all the users of discharge correspondence/summaries, not just GPs. The findings also highlight the need for user involvement in local and national design of discharge correspondence, and the balancing of the needs of specific recipients (for example the needs of GPs and CNTs) with accessibility of correspondence (length and structure). It was not clear to the investigation whether that balance could be achieved through one piece of correspondence, or multiple specific and bespoke pieces.

HSSIB makes the following safety recommendation

Safety recommendation R/2025/065:

HSSIB recommends that the NHS England/Department of Health and Social Care, in collaboration with relevant national bodies including the Professional Record Standards Body, adopts user-centred design principles to develop and validate new discharge correspondence templates for primary and community care settings. This is to provide standards for discharge correspondence that support recipients’ access to high-quality safety-critical clinical information, and that can be contextualised to local system needs.

3.2.10 As described in 2.2.7, the investigation saw variation in how discharge summary templates in hospital EPRs had been configured. Those EPRs also varied in their functionality and usability. Engagement with more digitally mature hospital providers demonstrated how more ‘functional’ EPRs had the potential to support users when producing discharge summaries (see Example A). A well-designed EPR was found to facilitate correspondence creation and helped ensure key information, such as about medications, was of high quality.

3.2.11 The investigation’s learning about EPR accessibility, functionality, interoperability and usability was extensive and beyond the scope of this investigation to consider effectively. In support of national learning HSSIB has launched a review of its work on EPRs to which this investigation will contribute.

Example A: An EPR that supports writing of discharge summaries

An acute hospital demonstrated the capability of its EPR to facilitate discharge communications. This involved a ‘discharge navigator’ which takes the clinician through pre-defined steps and draws information directly from the patient’s record into the discharge summary template. Of note was the functionality to reconcile medications and orders – including outstanding tests, results and scans – and the link with the prescription components of the EPR to provide the most recent medications information in the summary.

Investigation observation at a provider of acute hospital care

3.2.12 The investigation was also told by staff who write and are required to act on discharge summaries that they believed the quality of those summaries was poor because of a lack of training and ongoing education in how to write them (see 2.2.7). Several national stakeholders shared views that there was an absence of structured training for medical staff in writing discharge correspondence; this has also been described by researchers (Cresswell et al, 2015; Schwarz et al, 2019).

3.2.13 The investigation reviewed the General Medical Council (GMC) (2018) expected outcomes for medical school graduates for any focus on discharge correspondence. Outcomes included the ability for newly qualified doctors to collaborate and safely pass information including via electronic communications. The investigation did not explore with educational institutions whether writing discharge summaries was explicitly included in training. However, none of the medical staff engaged with recalled training, knowing “what good looks like”, supervised practice, or ongoing education to support the writing of discharge correspondence.

3.2.14 The investigation met with the GMC to explore the gap between the expectations of the outcomes for medical school graduates and the finding of potentially limited education around preparing discharge summaries. The GMC described that they are unable to approve individual medical school curricula and have limited influence over the delivery of undergraduate education. However, they have introduced a medical licensing assessment (MLA) from the academic year 2024-25 as a common threshold of safe medical practice in the UK (General Medical Council, 2025). The GMC confirmed they would use the findings of this report to inform future editions of outcomes for graduates and the MLA content map to support assurance that future doctors are ready for practice.

3.2.15 The investigation also engaged with the Medical Schools Council as the representative body for medical schools. The Council was supportive of strengthening the emphasis on discharge summaries in undergraduate education. It also highlighted the need for ongoing education and coaching around effective communications once in clinical practice. Several stakeholders described opportunities for ongoing professional development around discharge summaries within postgraduate education and through in-practice supervision and mentoring.

3.2.16 The investigation’s findings suggest a lack of structured and ongoing education for medical staff at undergraduate and postgraduate levels. While healthcare curricula may include the need for courses to consider the preparation of electronic information in support of care, the investigation repeatedly heard that this had not led to educational experiences that staff could recall nor that had influenced their practice.

3.2.17 The investigation considered whether to recommend a specific education intervention to support the writing of discharge correspondence. However, while training would be supportive, more fundamental issues around the culture of discharge communications (see 3.1.4), unclear expectations or knowledge of what recipients need from a discharge summary, and limited support to write a ‘good’ summary (see the template in 3.2.4 and the EPR example in 3.2.11) need addressing. These fundamental issues have contributed to the safety recommendations and local learning in this report.

Patient-facing correspondence

3.2.18 While the investigation did not explore the design of discharge correspondence from a patient perspective, it was heard that patient, family and carer insights are needed to help design accessible information for those users. This finding aligns with NHS England’s (2025c) recent publication setting out principles to reduce healthcare inequalities, including through making information clear and accessible.