A note of acknowledgement

We would like to thank the patients, charities, healthcare staff and healthcare organisations who engaged with this investigation for their openness and willingness to support improvements in this area of care.

About this report

This report is intended for healthcare organisations, policymakers and the public to help reduce patient safety risks in relation to temporary care environments. It summarises the analysis and findings of the Health Services Safety Investigations Body's (HSSIB’s) investigation, and provides a safety observation and learning prompts for organisations to consider when managing temporary care environments.

Executive summary

Background

This investigation explores the management of patient safety risks associated with using temporary care environments, often referred to as ‘corridor care’ and ‘temporary escalation spaces’. These are spaces not originally designed, staffed, or equipped for patient care (such as corridors, waiting rooms and chairs on wards). System-wide management of patient safety involves primary care, ambulance services, hospitals, community services and social care, and relies on effective patient flow. Temporary care environments are being used regularly due to pressures with patient flow where demand exceeds capacity. Their use requires a difficult compromise in patient experience, including privacy and dignity, in the interests of sharing risk and supporting patient safety.

This investigation specifically looked at acute hospitals in England, focusing on the patient safety aspects associated with the use of temporary care environments and how patient safety was being mitigated. The report explores how, where, when and why temporary care environments are used, what the associated patient safety risks are, and the impact on patients and staff.

This investigation is set against the context of challenges around demand, capacity and patient flow in the health and care system and did not focus on the wider factors which influence the need to use temporary care environments. This was due to the timescales and boundaries which the investigation was working to. Some of the factors that were not explored were internal and external processes that support the timely discharge of patients or patients who had been assessed as no longer needing to be in hospital. HSSIB's predecessor, the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB), has previously explored the flow of patients through and out of hospitals and made safety recommendations to the Department of Health and Social Care.

The investigation

The investigation observed the actions trusts were taking to mitigate the patient safety risks associated with temporary care environments. These risks included difficulty monitoring patients, insufficient staff for satisfactory staff to patient ratios, infection risk, a lack of piped oxygen and suction, and compromised response to medical and fire emergencies. The investigation observed the adaptations made in areas including staffing, the environment, equipment, and delivery of care.

The investigation was carried out between August and December 2025, recognising pressures around patient flow are constant and that temporary care environments are used throughout the year and not just during ‘winter pressures’. The investigation was carried out within a short time period so that learning could be shared with acute hospitals about what can be done to reduce patient safety risks and immediate harm when using temporary care environments. The investigation was therefore limited in its scope. It draws on observations from multiple hospitals and discussions with national stakeholders.

Findings

The findings in this report relate to the hospitals that the investigation engaged with. It recognises that this is a sample and there may be further variation across the health and care system and at different times of year.

- All staff the investigation engaged with were motivated to make things as good as they could for patients. There was a strong desire not to have to use corridor care (one form of temporary care environment).

- There was inconsistent data and information gathering which meant the impact of temporary care environments on patient safety may be poorly understood.

- There were limited reported patient safety incidents where the temporary care environment itself was recorded as a factor.

- National and local data on the time patients are in a temporary care environments is variable and inconsistent.

- There is variation in the language used to describe temporary care environments at a provider level. This can cause inconsistency in how national policy is applied, this impacts the findings above.

- There was governance processes associated with the use of temporary care environments. These include evidence of risk assessments to identify areas that can be used as temporary care environments, and to identify patients who may be more suitable for care in these spaces.

- Temporary care environments were located across hospital estates, in emergency departments and in ward areas. They included beds and trolleys in corridors, upright and reclined seating areas, extra spaces being made on wards or in cubicles, and other converted spaces, for example side storage rooms, office spaces and family rooms.

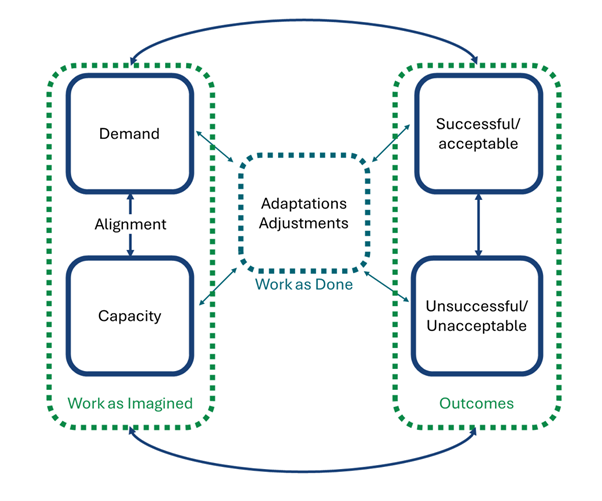

- Trusts were making adaptations and adjustments to the environment, staffing and delivery of care where possible to mitigate patient safety risks when using temporary care environments.

- Staff described feelings of moral injury (negative emotions that arise because they cannot provide the level of care they would like) caused by having to care for patients in temporary care environments and the resulting compromise in patients’ experience.

- There are patient safety risks that are more challenging to manage when using temporary care environments including medical emergency situations, fire safety and infection prevention and control.

- There is varied understanding of what quality of care (including patient experience) is compared to patient safety at all levels of the healthcare system.

- Concerns around normalising the use of temporary care environments can present a barrier to trusts putting all the possible patient safety mitigations in place when using temporary care environments.

- Improving patient flow would reduce the need to use temporary care environments.

- There was evidence of increased awareness by most hospital staff of pressures across the health and social care system including primary care, ambulances and social care. There was a recognition of the need to work together to share and mitigate risks to patient safety.

- There are internal processes that hospitals can improve to support functions that assist timely discharge, including using multidisciplinary teams in complex discharge processes.

HSSIB makes the following safety observation

Safety observation O/2026/080:

NHS regional and national organisations can improve patient safety by enhancing understanding of the use of temporary care environments across all hospital settings. This may include agreeing definitions of temporary care environments and enhanced information gathering on their use and impact on patient safety.

Local-level learning

HSSIB investigations include local-level learning where this may help organisations and staff identify and think about how to respond to specific patient safety concerns at the local-level.

Local-level learning prompts

HSSIB has identified the following local-level learning prompts for acute hospitals:

- Does your organisation have a policy that governs the use of temporary care environments that includes potential risk mitigation strategies? Do these policies consider the severity of patients’ health conditions, the appropriateness of patients who can be assigned to a temporary care environment and what exclusion criteria may apply in assigning patients to temporary care environments?

- Does your organisation use a multidisciplinary team to assist risk-based decisions on where to situate temporary care environments and make decisions on which patients are appropriate to be placed in them?

- Does your organisation consider the staffing ratios needed to manage temporary care environments, including numbers, skill mix, experience and competencies?

- Has your organisation nominated and assigned an individual healthcare professional to oversee temporary care environments, who is responsible for managing the completion of regular patient observations, escalating concerns, and standing back and providing leadership and supervision without being involved in direct care?

- Does your organisation have aligned processes across different departments, including the availability of specialty services to help facilitate the movement of patients to the right place of care as soon as possible?

- Has your organisation made adaptations to temporary care environment spaces that include having essential equipment nearby? For example, emergency call bells, communication systems, personal call bells, spaces for personal care and invasive treatments.

- Does your organisation have a means of tracking individual patients who are in a temporary care environment to support their clinical observations, understanding their needs and a process by which they document the length of time they have been in the temporary care environment?

- Does your organisation have a way of displaying clinical information and observations of patients in a temporary care environment to all relevant staff, so that trends or deterioration in a patient’s condition can be identified?

- Does your organisation provide information to patients about the use of temporary care environments and to inform them that any patient may be placed in one if there is a clinical need to provide a space for other patients?

- Does your organisation gather information about the use of temporary care environments including:

- the patient cohorts using temporary care environments

- a description of the temporary care environment

- how long patients have been in a temporary care environment

- incidents that have happened to patients while in a temporary care environment

- the immediate and long-term impact on patient safety and patient outcomes

- actions taken to reduce patient safety risks?

- Does your organisation ensure that patients in temporary care environments are regularly engaged with to ensure that they have food, water, are comfortable, understand what is happening to them and what the plan is going forward?

1. Background and context

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 This investigation explores the management of patient safety risks associated with using temporary care environments. There are several terms used to describe temporary care environments such as ‘temporary escalation spaces’, ‘corridor care’, ‘non-care spaces’, ‘flexible spaces’, and ‘seated majors’. The definition of temporary care environments is yet to be defined by the Department of Health and Social Care. For the purposes of this investigation, temporary care environments are defined as ‘spaces that are not designed, staffed or equipped for care delivery such as waiting rooms, corridors, chairs on wards, ambulances outside emergency departments (EDs), and other areas of the hospital not designed for in-patient care’ (Royal College of Physicians, 2025a).

1.1.2 Temporary care environments are being used on a regular basis as a response to patient flow pressures within acute hospitals (see section 1.3). There is evidence that there is no longer seasonal variation and that the pressures around patient flow are constant. A recent publication highlighted that the challenge of having to use temporary care environments ‘persists beyond the winter months, with 59% of doctors reporting they provided care in temporary settings over summer 2025’ (Royal College of Physicians (2025b).

1.1.3 There is widespread concern among national stakeholders that using a temporary care environment poses risks to patient safety, is not acceptable and should not be ‘normalised’ (Care Quality Commission, 2025; NHS England, 2025a, Royal College of Nursing, 2024a). A survey found that around half of respondents indicated concerns around patient safety when using temporary care environments. These included, ‘safety being compromised, difficulty in monitoring patients, and problems accessing vital equipment’ (Royal College of Nursing, 2024a).

1.1.4 The investigation engaged with national organisations and trusts across England to understand:

- how, where and when temporary care environments are used

- the needs of patients using temporary care environments, including those from vulnerable patient groups, and the associated patient safety issues

- the impact of temporary care environments on patients and staff and how organisations manage the associated patient safety risks.

1.1.5 The investigation was conducted within a short time period to support the sharing of learning with acute hospitals and was therefore limited in its scope. The investigation observed multiple temporary care environments in seven hospitals across England between August and October 2025. Insights were also shared from a concurrent investigation into Safety issues for people experiencing a mental health crisis who come into contact with urgent and emergency services. Therefore, evidence collected at a further six hospitals in November and December 2025 was also considered. The appendix of this report outlines how the hospitals were selected. The investigation also held remote discussions with staff at four other hospitals, an ambulance service, and with national stakeholder organisations.

1.1.6 The investigation recognises that there are different practices in different trusts which may not have been captured in this investigation.

1.2 National guidance on using temporary care environments

1.2.1 NHS England (2025a) has published guidance on ‘Principles for providing patient care in corridors’. NHS England states ‘the delivery of corridor care in departments or wards experiencing patient crowding to be unacceptable and should never be considered standard… However the current healthcare landscape means that some providers are using corridor care more regularly – and this use is no longer in extremis’.

1.2.2 NHS England outlines six core principles including:

- Assessment and mitigation of risk – considering the risk for potential harm and safety for staff and patients who are being considered for care in the temporary care environment.

- Escalation – providers having escalation models in place and organisational governance around the use of temporary care environments.

- Quality of care – standards of care must be maintained including aspects such as dignity, patient-centred care, nutrition and hydration, sleep, and monitoring.

- Raising concerns and reporting incidents – staff must be able to speak up freely and report concerns or incidents relating to temporary care environments.

- Data collection and measuring harm – providers must monitor the use of temporary care environments, collect data and track incidents and complaints so that learning can be shared.

- De-escalation – there must be a clear process for stepping down the use of a temporary care environment with board oversight, debriefs and reviews.

1.2.3 The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) (2024b) responded to the NHS England guidance directing trusts to actively monitor and report the impact of temporary care environments. While the RCN welcomed this as a first step, it felt further work was needed and called for reporting to be mandatory rather than optional. Drawing on its own survey data (in which over 1 in 3 nurses reported providing care in temporary care environments on their last shift), it emphasised that caring for patients in these environments should not be normalised.

1.2.4 The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) (2025a) issued a position statement on the use of temporary care environments, acknowledging their growing use which they deemed to be ‘unsafe and unacceptable’. The RCP called for the NHS and government to formally measure and publicly report on the care being delivered in these spaces, year round and not just during winter pressures.

1.2.5 The RCP (Royal College of Physicians, 2025a) issued a practical set of recommendations for hospitals and local healthcare systems as well as clinicians, when working within temporary care environments. It recommended co-ordinated system-level planning between hospitals, community, and social care services to improve patient flow, reduce discharge delays, and expand appropriately staffed and equipped inpatient spaces. Clinicians were encouraged to prioritise timely assessment and teamwork to minimise the time any patient spends in an unsuitable location.

1.2.6 The Royal College of Emergency Medicine (n.d.a) outlined in its ‘Roadmap to recovery’ that often patients waited for care for an unacceptable amount of time in EDs, and that some patients ended up being cared for in ‘inappropriate spaces such as corridors’. It urged the government to address emergency care pressures by ensuring adequate, well-staffed hospital bed capacity and investing in community and social care to improve patient flow and reduce overcrowding. Other demands of the government included expanding and retaining the NHS workforce through more training places and better working conditions, ensuring suitable funding and setting transparent performance standards to promote accountability.

1.2.7 Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) is a national NHS England programme aimed at improving patient care by reducing unwarranted variation across healthcare services. The programme has issued several publications to enhance urgent and emergency care services across the NHS. In 2024, GIRFT, in collaboration with the Royal College of Physicians, introduced 10 core principles aimed at improving patient flow and experience (Royal College of Physicians, 2024).

1.3 Patient flow into, through and out of hospital

1.3.1 Temporary care environments are being used when there is a ‘lack of capacity within health and care systems to manage the demand for patients requiring urgent and emergency care’ (Royal College of Physicians, 2025a). Research with 165 ED’s has shown that in March 2025, 10,042 (17.7%) patients received care in a temporary care environment (Trainee Emergency Research Network, 2025). Another article highlights that nearly 1 million ED patients have been placed in corridors or similar ‘temporary’ spaces over the past year (HSJ, 2025). Both data was focused on ED and does not include other areas of the hospital where temporary care environments are used, so the numbers are likely to be higher.

1.3.2 An investigation by HSSIB’s predecessor organisation, the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB) (2023), discussed the flow of patients through and out of hospitals and made safety recommendations to the Department of Health and Social Care. Patient flow remains a significant national issue. The issues and challenges within this report are a direct consequence of poor flow and will remain until this issue has been addressed. Until that time, local organisations have to mitigate the risks that arise as a result of poor flow, which are highlighted in this report.

1.3.3 Many initiatives are in place across the healthcare system to try and improve patient flow. Nationally, the W45 (withdraw at 45 minutes) standard applies (NHS England, 2025b) which indicates that handover of patients from ambulance to hospital staff should be done within 15 minutes and take no longer than 45 minutes. The implementation of the W45 rapid release protocols has been a critical measure to address the persistent challenge of ambulance handover delays at EDs (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, 2025a). These delays not only compromise patient care but also significantly reduce ambulance availability for new emergencies, posing high risk for patients who may need life-saving and rapid intervention, for example for strokes or heart attacks (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, 2025b).

1.3.4 The operational standard for accident and emergency waiting times states that people arriving at an ED should be admitted to hospital, transferred to a more appropriate care setting, or discharged home within 4 hours (Department of Health and Social Care, 2025b; NHS England Digital, 2024). This performance standard has been missed every month since July 2015 at a national level (The Kings Fund, 2024).

1.3.5 In addition, in England, the NHS requirement is that no more than 2% of patients should wait 12 hours or more from their time of arrival. This pledge has not been met in England since April 2021 (Royal College of Emergency Medicine, n.d.b). A report on the state of care in England (Care Quality Commission, 2025) states that in 2024/25, 1,809,000 people waited over 12 hours from the time of their arrival, up 10% from the previous year. A quarter of 12-hour breaches are patients with mental health needs (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2025).

1.3.6 There is a national challenge where there is a large volume of patients who are medically ready to be discharged but remain in hospital due to pressures across community and social services (Care Quality Commission, 2025; Nuffield Trust, 2025). Many of the challenges around ambulance waiting times, patient discharge from hospital, and community and social services are highlighted in the ‘State of health care and adult social care in England 2024/25’ (Care Quality Commission, 2025).

1.3.7 It is recognised that delayed discharge impacts on hospital crowding and ED patient flow (Khanna et al, 2016; NHS England 2025c). National discharge guidance (NHS England, 2024a) emphasises co-operation between healthcare providers and local authorities to agree discharge models that meet local needs. It also highlights the importance of involving families and carers, and contains specific guidance on the use of care transfer hubs (a physical and/or virtual co-ordination hub whereby all relevant services are linked together to co-ordinate discharge support) to support the discharge of patients with complex needs.

1.3.8 Many hospitals use ‘boarding’ as a way to improve patient flow from the ED and create capacity. Boarding is where a patient is moved to a ward before a bed is available for them and may involve them sitting in a corridor on a ward while they wait for a bed. The Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM) issued guiding principles around boarding stating that the patient who is boarding in a ward environment most likely poses a lower patient safety risk than a growing number of unassessed and untreated patients awaiting ED assessment. It also stated it is the safest approach when a provider cannot cope with demand, to use all available resources across the hospital to manage the problem (Royal College of Emergency Medicine, 2024). The RCN told the investigation that themselves and others have previously highlighted concerns about boarding which also has safety and patient experience risks (Strategic Research Alliance, 2024).

1.3.9 Various flow models exist across the healthcare system to try and support patient flow through and out of hospital (Flow Coaching Academy, n.d.; Sheffield Microsystem Coaching Academy, n.d.; Vaughan and Bruijns, 2022). The ‘continuous flow model’ works by moving a set number of patients directly to inpatient wards from the ED at set intervals, irrespective of whether there are any beds available, to create capacity in the ED (Lingham, 2022).

1.3.10 GIRFT launched the ‘Further Faster’ workstream in 2025 focusing on strengthening urgent and emergency care pathways (NHS England, 2025d). This initiative provided support to NHS trusts, aimed at improving ambulance response times by reducing handover delays, enhancing ED performance, reducing long waits and shortening patient length of stay to improve flow.

1.4 Defining safety and quality?

1.4.1 The review of patient safety across the health and care landscape (Department of Health and Social Care, 2025a) suggested that quality is recognised as ‘multi-dimensional’ and ‘these dimensions typically include safety, effectiveness and patient or user experience, as well as accessibility, equity and efficiency’.

1.4.2 NHS England defines the oversight of quality as ‘the ongoing monitoring of performance and quality of services being delivered by the NHS, to manage the delivery of the priorities set out in NHS planning guidance, the NHS Long Term Plan, and the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan. Its purpose is to provide assurance of performance and delivery as well as identify areas of challenge and those requiring support or intervention’ (NHS England, 2024b). Safety management processes are not mentioned as part of this definition of the oversight of quality.

1.4.3 The Care Quality Commission (2024) has fundamental standards of care which underpin its regulation of healthcare providers, under The Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014. Within these regulations, safety is considered separate to other standards of care including dignity and respect, and person-centred care.

1.4.4 Regulation 12 (Safe care and treatment) outlines nine things that a registered provider must do to comply with the regulation. These include assessing and mitigating health and safety risks to patients, ensuring premises for providing care are safe for their intended purpose and that equipment and medicines are available and managed safely, and managing risks associated with the spread of infection.

1.4.5 Other fundamental standards which relate more to the quality of care and patient experience include regulation 9 (person-centred care), regulation 10 (dignity and respect) and regulation 14 (meeting nutritional and hydration needs).

1.4.6 Safety is the framework of organised activities that creates cultures, processes, procedures, behaviours, technologies and environments in healthcare that consistently and sustainably lower patient safety risks, thereby reducing the occurrence of an avoidable harm (World Health Organization, 2021). Quality is about consistency, reliability, and meeting user expectations (International Organization for Standardization, 2015).

1.4.7 It is accepted across all safety-critical industries that quality is about reducing variability and assuring compliance to standards, while safety is about managing situational safety risks that are recurrent or newly identified (International Organization for Standardization, 2018). While certain standards of care can encompass quality and safety, it is important that these are also considered separately.

2. The patient safety issue

2.1 Described patient safety issue

2.1.1 The investigation spoke to patients, staff and several national healthcare organisations to better understand the key patient safety challenges when using temporary care environments.

2.1.2 The investigation found that when discussing patient safety, the issues were often related to privacy, dignity and quality of care rather than patient safety concerns (see section 3.3.10). However, the patient safety issues described that could occur included:

- Difficulty monitoring patients as they may be located away from main areas and out of lines of sight.

- Having an insufficient staff to patient ratio and skill mix to support temporary care environments.

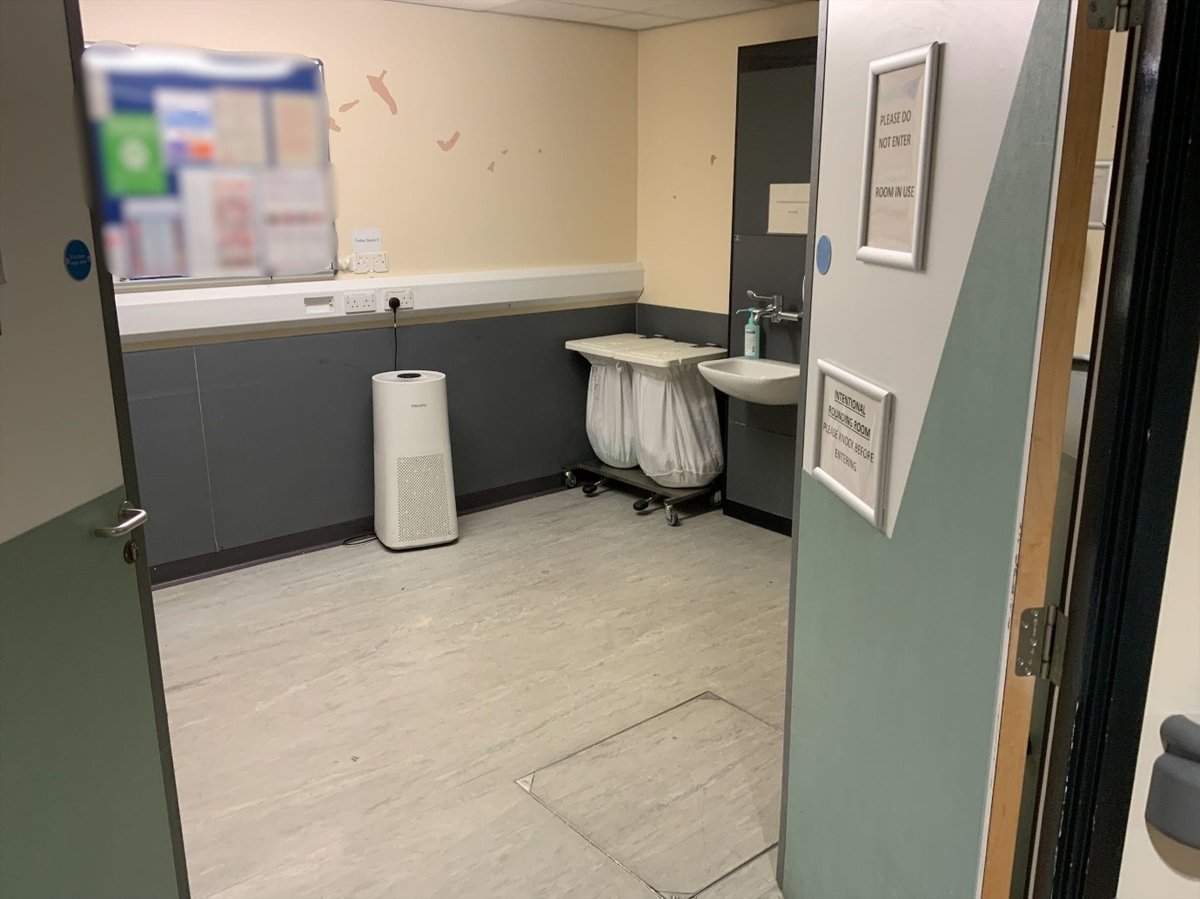

- Increased risk of infection due to chairs, trolleys and beds being in close proximity in temporary care environments (see figure 1), a lack of hand washing facilities and being in a high footfall area.

- A lack of piped oxygen and suction. Oxygen cylinders under the trolleys may be used instead which could run out without staff noticing. A previous HSIB investigation reported on this (Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch, 2018).

- Compromised response to medical emergencies in temporary care environments where there is no emergency buzzer to alert staff, access to the patient is more awkward and emergency equipment may not be immediately accessible.

- Fire and fire evacuation risks associated with an increased number of patients to evacuate, fire doors being propped open, restricted access to fire extinguishers, and fire escape routes being obstructed due to temporary care environments.

- An increased risk of pressure damage or falls, especially for frail and/or older patients who may be located in a temporary care environment out of direct sight and without a call bell.

- An increased risk of delirium for elderly people who may find a temporary care environment disorientating and/or placed into a temporary care environment which is noisy.

- Mental health patients may be able to abscond or access items for self-harm due to limitations in visibility in some temporary care environments. A separate HSSIB investigation is exploring Safety issues for people experiencing a mental health crisis who come into contact with urgent and emergency care services.

Figure 1 Patients on trolleys in a corridor being used as a temporary care environment due to overflow in the emergency department

3. Local evidence and findings

This section sets out the findings of the investigation and provides learning prompts for trusts to consider when managing temporary care environments. A safety observation is also made for regional and national healthcare organisations. The findings are structured under the following headings:

- Patient and staff experience.

- Reporting on the use of temporary care environments.

- Conditions for managing patient safety risk.

3.1. Patient and staff experience

3.1.1 It was evident from speaking with patients, staff and national organisations that the use of temporary care environments causes challenges around privacy and dignity. This can result in distress to both patients and staff, which are described in this section.

Impact on privacy, dignity and patient experience

3.1.2 The investigation spoke to patients who were being cared for in beds, trolleys or chairs in corridors in emergency departments (EDs) or on wards. Most of the patients who were in EDs were waiting for a place on a hospital ward or waiting to be discharged.

3.1.3 Many of the patients in EDs said they were grateful that they were now on a trolley or bed and described it being “better being here [on a trolley in a corridor] than sitting in a chair in the waiting room”. Other patients and staff commented that it was better being on a bed in a corridor than being in an ambulance waiting to be seen or at home waiting for an ambulance to arrive.

3.1.4 In many circumstances patients had been given information in the form of a letter when they entered the ED, stating that they may have to be cared for in a temporary care environment due to the number of patients in the ED and wider hospital.

3.1.5 Patients commented that they did “not want to complain” and displayed a stoic resilience because they could see how busy staff were and that they were trying their best to look after them and other patients.

“I don’t like to make a fuss because there are lots of sick people here and the nurses are run of their feet …”

Patient in temporary care environment

3.1.6 The investigation recognises that a small sample of patient perspectives were gathered during site visits and that there is varied data and perspectives on the experience patients have in a temporary care environments.

3.1.7 Several patients who were in temporary care environments in EDs told the investigation that they had challenges with personal care, such as washing and toileting, or having to be given invasive treatments such as insertion of cannulas or drips. Patients understood that there had been a compromise with being in that environment or being somewhere else less safe.

3.1.8 Patients said that despite the privacy and dignity concerns they “felt safe” and “well looked after”. Many patients were able to describe what their care plan consisted of, what was going to happen next, what tests they were waiting for, and when they might move to a ward in the hospital or go home. Patients said they knew who was caring for them and that staff had introduced themselves, and how this made a significant difference to them.

3.1.9 The investigation noted in national reports (for example, Age UK, 2025; Royal College of Nursing, 2025) that patients may be left for hours without access to food or drink. This can especially be a risk for older and frail patients who can deteriorate quickly if dehydrated or malnourished. During the observation visits patients said they had been given water, tea and both warm and cold food on a regular basis. The investigation observed staff in EDs asking if patients needed anything, if they were comfortable, or if they had any concerns. This was observed to be happening continually during the investigation's visit.

“… the nurses are great, they are very busy but they ask me if I’m OK and if I need anything.”

Patient in temporary care environment

3.1.10 The investigation explored with patients what ‘safe’ meant for them. Many went on to describe privacy concerns and feeling unsafe when they had to have a difficult or private conversation with a member of staff, or with family members. The investigation observed a consultant speaking to a patient in a crowded and confined seating area. The investigation did not hear the conversation but saw the patient become visibly upset and then trying to hide themselves from others.

3.1.11 At one site visited as part of a concurrent HSSIB investigation exploring mental health crisis, patients described being fearful because there were several people in mental health crisis in temporary care environments who were shouting and pacing around the emergency department. These patients were mentally very unwell and were either awaiting a Mental Health Act (1983) assessment or admission to a mental health inpatient ward. One patient who had attended the emergency department with new onset headaches left as she felt “scared” and “it was too noisy”.

3.1.12 Patients said that getting into and out of bed in a busy corridor could be challenging, particularly for those who were older or frail. Patients said that on many occasions staff had taken patients into side rooms for personal care (see figure 2) or escorted them to a toilet if they were frail. They also said if staff were busy, then there was no-one to take them to the toilet and they either had to hold on or soil themselves.

“The corridor is busy, non-stop. I take a long time to get out of bed and am unsteady on my feet and need help moving around. When it is busy, it’s much harder [to move around] and I’m scared I’ll get knocked off my feet.”

Patient on trolley in hospital corridor

Figure 2 Example of a side room adapted for personal care and treatment in a temporary care environment

3.1.13 The investigation was told that hospitals had been analysing complaints data to improve their service. For example, following a review of complaints, one hospital had started to hand out hospital canteen hot food vouchers for patients who had been in a temporary care environment for more than 12 hours. If the patient was unable to get to the canteen, a member of staff would go to the canteen to place and collect their order.

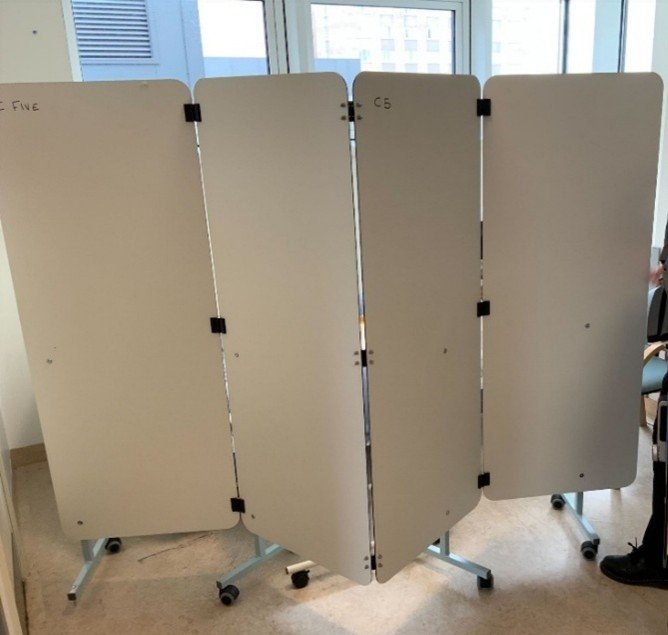

3.1.14 To aid privacy and dignity, one hospital had installed curtains in the corridor, which could be tucked away when the temporary care environment was not in use. Other hospitals used privacy screens (see figure 3). Hospitals had also adapted nearby spaces such family rooms and large store cupboards or kept a room available to accommodate patients’ personal care needs.

Figure 3a and 3b Examples of screens used to provide privacy and dignity

Figure 3a

Figure 3b

3.1.15 Overall, the investigation found that direct reports of patient safety concerns from patients was limited. However, there was evidence that privacy, dignity and patient experience could be compromised in a temporary care environment. The investigation found that staff were doing all they could to provide the best care they could and were implementing adaptations to improve patient experience where possible.

Impact on staff

3.1.16 The investigation engaged with many staff members during site visits. Several Emergency Medicine (EM) consultants and nurses spoke about personal challenges in balancing the use of temporary care environments and giving the care to patients they felt was needed. The investigation heard from staff at all levels that they struggle to care for people in temporary care environments. Frequently the phrase “this isn’t what I trained for” or “this isn’t what I thought I’d signed up for” was heard. Caring for people in an environment not designed for care and therefore not being able to give patients privacy, dignity or the level of care that staff would want was reported to create moral injury to staff. Moral injury refers to negative emotions such as guilt, shame and anger that result from a violation of a person’s moral values. There is a clear link between moral injury and patient safety (Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch, 2023). For example, moral injury reduces staff’s ability to process information, can reduce team cohesion, and can lead to physical exhaustion because of the impact of stress on sleep. Previous HSIB recommendations have highlighted the importance of considering staff health and wellbeing in patient safety strategies.

3.1.17 Staff spoke about the difficulties in having private and difficult conversations with patients in a public space. They said they knew that this was not ideal, but there was nowhere else to have the conversation. One consultant said they had to give a patient news that they had identified a new and aggressive cancer while carrying out tests in the ED to assist diagnosis, and that it was not appropriate to discuss this in the corridor. They said they had to wait until another patient was well enough to move out of a bay in the ED before moving this patient into the bay so they could have the conversation. They said this decision was made to support the patient’s privacy and dignity rather than medical need or safety concerns.

3.1.18 Similarly, a ward consultant told the investigation that when they have to see patients in a temporary care environment, particularly when in a corridor, “it is very difficult to have private conversations”. However, the investigation observed that having private conversations with patients who are not in a temporary care environment can also be challenging as there may only be a curtain between patients and they are relatively close to each other.

3.1.19 All the nurses the investigation spoke with said that caring for people in temporary care environments was not what they wanted to do, but acknowledged the alternative could be worse for patients. Many doctors and nurses told the investigation that using temporary care environments was the “best worse” option. Leaving people at home, in ambulances or unseen in waiting rooms were the worst options.

3.1.20 Several nurses who had been allocated responsibility for the care of patients “in the corridor” for their shift, told the investigation it was “horrible” caring for people in temporary care environments due to the limited privacy and dignity they could offer patients. They did say that in many cases additional adapted spaces had been made available for personal care and invasive procedures. All the nurses said there was less room around patients to carry out their tasks and it could be difficult to manoeuvre equipment around, but they could give the nursing care needed.

3.1.21 Staff explained they could be looking after up to six patients at any one time. Most nurses said they had a dedicated health care assistant (HCA) to support them. Across the site visits, the investigation observed that the nursing ratio for patients in temporary care environments ranged from one nurse to four patients to one nurse to six patients, not including HCAs. This was reported to be a satisfactory staff to patient ratio. The investigation heard that staffing ratios are based on several factors, such as acuity (the seriousness of patients’ medical condition and level of care they need), the number of patients and the skill level needed, and may vary between different hospitals, departments and wards. NHS England provides guidance on safer staffing for nursing, including workforce planning and recommendations on reporting and governance arrangements (NHS England, n.d.a).

3.1.22 While the investigation was told that staffing levels were suitable during site visits, there is evidence that staffing levels may not always be suitable in temporary care environments. The Royal College of Nursing (2025) highlight staffing challenges and the risk this poses to patient safety.

3.1.23 The investigation was told by staff at all levels that staff were experiencing fatigue and burnout because of the number of people that had to be cared for in temporary care environments. The Royal College of Nursing (2025) also reported staff burnout and fatigue, higher levels of stress, and people being more worried or emotionally burdened by not being able to give quality care. They also reported that staff were leaving the profession because they could not give the quality of care that they had trained for.

3.1.24 Overall, it was evident that the impact of using temporary care environments was having a significant impact on staff wellbeing. The links between patient safety and staff fatigue/staff wellbeing have previously been investigated by HSSIB (Health Services Safety Investigations Body, 2025; Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch, 2023).

3.2 Reporting on the use of temporary care environments

3.2.1 The definition of temporary care environments varies across organisations; this complicated efforts to understand and evaluate their use. As highlighted in section 1 of this report, several terms are used to describe temporary care environments and definitions are yet to be agreed by the Department of Health and Social Care. Without consistent metrics or definitions, it is difficult to evaluate the impact of these environments on patient outcomes (positive and negative) or to compare practice across settings.

3.2.2 There were limitations in the patient data collected within temporary care environments. These environments differ significantly in design and staffing, with different levels of risk associated with them. Current reporting does not reflect this variation or consider the broader context, such as which patients are placed in these settings, for how long, and under what circumstances.

3.2.3 The hospitals visited did not have Patient Safety Incident Investigations (PSIIs) associated with temporary care environments. While some trusts reported occasions where patients were inappropriately placed in such environments and actions were taken to relocate them, these instances were not consistently documented. The investigation also reviewed coroner prevention of future death reports associated with temporary care environments and found that they did not clearly articulate how the environment may have contributed to the event. This lack of contextual detail and clarity in reporting limits understanding of the safety risks associated with temporary care environments.

3.2.4 The investigation acknowledged that patient harm linked to temporary care environments may not always be immediately visible. Harm can occur shortly after a patient is placed in such an environment, but may also emerge over a longer period. The impact of temporary care environments on patient safety may not be captured at the point of care. However, due to the data issues discussed in this report, it is unlikely that harm that occurs beyond the point of care is being systematically captured.

3.2.5 Data limitations also extend to how temporary care environments are monitored and measured. There is inconsistency in how trusts record the length of time patients spend in these environments, with some “stopping the clock” when there are delays in decisions to admit a patient, making the duration of stay difficult to measure. Additionally, the continual use of these spaces with a rolling flow of patients makes it difficult to capture discrete episodes of care or assess cumulative risk.

3.2.6 Transparency around the use of temporary care environments remains limited, with few mechanisms in place to support organisational learning or the systematic capture of patient safety data. Because hospitals have been told by national organisations that they should not be used, there may be a reluctance to report how they are being used. The investigation found that some trusts report that they do not use temporary care environments; further inquiry reveals that they are using spaces that meet the same criteria but use different terminology. This may obscure the reality that patients are being cared for in environments not originally intended for clinical use or in environments that have been modified to accommodate more patients than they were originally designed for. This variation creates challenges for transparency, data consistency and cross-organisational learning.

3.2.7 The absence of consistent reporting frameworks means that the impact of temporary care environments on patient safety may be poorly understood. This lack of visibility may contribute to inconsistencies in how data is interpreted and used, resulting in an incomplete picture of the risks and outcomes associated with these environments. However, some trusts have taken proactive steps to monitor and manage their own data on temporary care environments, developing local systems to track usage and inform decision making. These efforts highlight the potential for more robust and transparent approaches.

HSSIB makes the following safety observation

Safety observation O/2026/080:

NHS regional and national organisations can improve patient safety by enhancing understanding of the use of temporary care environments across all hospital settings. This may include agreeing definitions of temporary care environments and enhanced information gathering on their use and impact on patient safety.

3.3 Conditions for managing patient safety risk

3.3.1 The investigation found that many of the hospitals it engaged with were considering and mitigating the patient safety risks (see section 2) associated with using temporary care environments as part of their overall risk management. This section discusses how hospitals were maintaining oversight and managing risks associated with temporary care environments, the adaptations they were making, and the actions being taken to reduce the need for temporary care environments. It concludes with practical considerations for healthcare organisations for mitigating patient safety risks when having to use temporary care environments.

Oversight and risk management

Balancing patient safety risk

3.3.2 Temporary care environments were being used when patient demand exceeded the capacity of the hospital. Many of the hospitals engaged with had previously had issues with their ambulance waiting times and with the introduction of W45 (see 1.3.3), there was an impetus to get people into the hospital, despite there not being enough beds. Hospitals reported a greater use of temporary care environments since the introduction of W45.

3.3.3 Trusts told the investigation that W45 improved ambulance response times in the community and the Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE) shared case studies where trusts had effective interventions to reduce handover times (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, 2025b). One trust also said that ‘On occasion patients are identified in non-clinical areas (receptions etc) that have seemingly been left by their paramedic crew at the 45 minute mark, but without communicating to our team with any sort of handover. On occasion the local team did not even know the patient was in the department at all.’ The unintended consequences of W45 have also been highlighted by Patient Safety Learning (2025).

3.3.4 Staff described that where demand and discharge delays surpass capacity, difficult decisions were having to be made to balance these risks and not increase the risk to patient safety. The investigation heard that using temporary care environments meant there may be a need to compromise patient experience, including privacy and dignity, in the interests sharing risk and supporting patient safety.

3.3.5 The investigation found hospitals were trying to balance patient safety risk by “spreading the risk” across the hospital and wider health and social care system (see 3.3.63). By using temporary care environments across the organisation, it reduced the “ambulance queue” and released ambulances to respond to emergencies and mitigate unknown risks in the community, rather than not using temporary care environments and ambulances not being able to respond to new emergencies.

3.3.6 There was variation in how hospitals were implementing risk mitigations and adaptations for temporary care environments. The investigation heard and observed that previous negative experiences of using temporary care environments due to media coverage and external pressure from national organisations “not to normalise” can present a barrier to putting all the possible mitigations in place. As highlighted in section 1, NHS England (2025a) guidance states ‘the delivery of corridor care in departments or wards experiencing patient crowding to be unacceptable and should never be considered standard…’. The Care Quality Commission highlighted in a report that it remains concerned about the use of temporary escalation spaces, stating that ‘Patients should receive safe and effective care in an environment that allows for their privacy and dignity to be protected, and that corridor care must not become normalised’ (Care Quality Commission, 2025).

3.3.7 The national, media and public perspective on reducing the need for temporary care environments does not always acknowledge that temporary care environments are considered “as a last resort” by hospitals and decision to use them is “not taken lightly”. The investigation found there is a contrast between the messages that national organisations and the media are conveying and the system-wide risks being managed on a daily basis. NHS England (2025a) has acknowledged that these spaces are being used. It states that ‘the current healthcare landscape means that some providers are using corridor care more regularly – and this use is no longer in extremis’.

3.3.8 The investigation heard from several hospital senior staff that they did not want to make physical adaptations to temporary care environment spaces (such as addition of electric points or emergency call bells) because they did not want to “normalise” their use. Other hospital senior staff said they had adapted spaces because the reality of their experience was that they could not avoid using these spaces, so they had invested in physical adaptions (see Figure 4 and 3.3.45 to 3.3.52). In all cases observed by the investigation, temporary care environments were being regularly used. Senior staff told the investigation there was always a drive to reduce or eliminate the need for temporary care environments.

3.3.9 In other safety-critical industries, emergency and ‘worst case scenarios’ are planned, trained and equipped for. For example, evacuation slides are fitted to aircraft, lifeboats on ships and crews are trained in their use. In hospitals, there are fire emergency protocols and equipment should a fire emergency occur. The aim is not to use the emergency facilities, but they are there for safety purposes to help save lives if the worst case scenario should happen.

Figure 4 Example of an adapted temporary care environment in a corridor in an emergency department, with an electric point and emergency call bell

Understanding of patient safety risk and quality of care

3.3.10 Section 1.4 of this report outlines what is meant by quality and safety. An HSSIB report (Health Services Safety Investigations Body, 2024a) found that the language used in relation to quality and safety varied in different settings and was used differently by staff and patients in those settings. The report stated that ‘Simple and consistent language is critical to driving improvement in healthcare …’ but that language was used ‘interchangeably which causes confusion for staff and patients’. The report recognised that quality and safety are different but have shared components. It highlighted that ‘you can deliver completely safe services which don’t have good overall clinical outcomes/effectiveness whilst people may have the best experience but come to avoidable harm’.

3.3.11 In mature systems of safety, it is recognised that safety and quality need to be managed in tandem. In aviation in particular, an integrated management system approach is gaining momentum (International Civil Aviation Organization, 2018). However, while quality and safety are being considered together, they are still two separate entities and have their own individual management systems. A previous HSSIB investigation heard from other industries that if the management of safety and quality are combined within a single policy or management process, quality is the easier challenge to tackle than safety, and therefore the focus on safety can be lost. They also said that accountability for safety is a distinct function from that of quality (Health Services Safety Investigations Body, 2024b). As highlighted in the background section of this report, there is variation in how safety and quality is considered across national healthcare organisations.

3.3.12 The investigation explicitly explored patient safety concerns associated with temporary care environments with staff, trust senior managers and national bodies. While patient safety concerns such as infection control were raised, concerns around the quality of care and patient experience were predominantly discussed. Privacy, dignity and patient experience issues and the impact these had on staff also tended to be discussed in national reports and surveys relating to temporary care environments (for example, Royal College of Nursing, 2025; 2024a). As such, there is varied understanding of what quality of care (including patient experience) is compared to patient safety at all levels of the healthcare system, which may impact how safety risks are balanced and managed.

Hospital oversight of temporary care environments

3.3.13 The hospitals the investigation engaged with all had policies and standard operating procedures for using temporary care environments. Staff told the investigation that the use of temporary care environments was a “last resort”. However, most organisations had adopted an organised and collaborative way of managing patient safety risk and patient flow through their hospital.

3.3.14 Factors considered for using temporary care environments were the trust’s Operational Pressures Escalation Levels (OPEL) score (a score which indicates a trusts operational pressure (NHS England, 2025e)), number of patients, acuity of patients, number of patients with a stay more than 12 hours, number of ambulances waiting to hand over patient care, resuscitation capacity, and clinical judgement. The decision to use temporary care environments was made at a senior management level in the hospital, by board directors and executives, and was informed by regular governance meetings between senior management and nursing leads in each department of the hospital (see 3.3.17).

3.3.15 A previous investigation (Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch, 2023) explored how siloed working in hospitals, lack of understanding of pressures in EDs and the number of people waiting in ambulances to be seen by a clinician impact safety across the healthcare system. In this investigation, during discussions with staff across hospitals, the language around ‘whole system’ patient safety risk had changed. There was increased awareness of relieving pressure on ambulance services and EDs, taking more responsibility to share the pressure and patient safety risk across the hospital by accepting patients into temporary care environments on wards. Senior staff said that there had been significant movement toward their hospital departments working together to reduce patient safety risks. Senior staff said that this change in awareness was a significant shift in thinking and would need time to embed.

3.3.16 The investigation observed different levels of maturity of thinking around sharing the risk when using temporary care environments. Some hospitals had embedded the sharing of risk across the organisation for some time; others were still concentrating the use of temporary care environments in the ED. For example, several ED doctors and nurses at one hospital told the investigation that senior management were trying to tackle the challenges at the ‘front door’ by managing the risk across the hospital. However, they felt that the pace of working in other areas of the hospital did not match the higher pace at which they worked so there was an imbalance. They felt this imbalance meant that the ED was seeing and referring many patients but internal processes and limitations in understanding ED pressure prevented the whole hospital adopting a cohesive approach to managing flow across the system. This then led to more temporary care environments being used in the ED, particularly for patients where a decision to admit them to hospital had been made.

Regular and routine governance meetings

3.3.17 The investigation observed several routine meetings that related to the ‘live’ situational challenges being faced. These meetings had different names such as ‘operational planning meetings’, ‘bed management meetings’ and ‘patient flow meetings’. The purpose of all of these meetings was to try to improve the flow of patients through the hospital where possible, spread the risk with the use of temporary care environments, and explore potential discharge of patients to free up beds. All meetings discussed which wards could take additional patients, balancing a multitude of factors including staffing situations, in particular where wards did not have a full complement of staff.

3.3.18 In many of these meetings it was observed that there was an ‘exchange of numbers’ and aim to discharge ‘x’ number of patients. In other meetings there were clear actions around patients and their needs to help manage flow. For example, where a patient needed admission to a mental health ward, there was evidence of senior hospital staff from mental health and acute care working together to try and manage risks.

3.3.19 The investigation observed that as a result of the regular governance meetings to co-ordinate patient flow, hospitals were able to de-escalate and even close temporary care environments for periods of time, then expand back into them as necessary.

Adaptations made

3.3.20 The investigation used a resilient healthcare approach, recognising that services, teams and professionals are adapting in times of increased pressure. This was to help identify opportunities where the trusts may support the use of adaptations by staff, within safe limits, to cope with these challenges (Centre for Applied Resilience in Healthcare, 2020; Page et al., 2023).

3.3.21 The investigation specifically identified adaptations and adjustments that hospital staff and senior management had made to the environment, staffing, and delivery of care to mitigate patient safety risks when using temporary care environments.

Considering where temporary care environments are used

3.3.22 The majority of the hospitals the investigation engaged with used temporary care environments across the hospital – in the ED, acute medical units, and on hospital wards – to share the risk of patient demand surpassing the capacity of the hospital. One hospital visited only used temporary care environments in the ED; this was reported to be an executive decision.

3.3.23 The investigation found there was variability in the temporary care environments that were being used which had different patient safety risks associated with them. Temporary care environments encompassed beds and trolleys in corridors, upright and reclined seating areas, extra spaces being made on wards or in cubicles, and other converted spaces, for example side storerooms, office spaces and family rooms. Hospital beds that had been added to a ward often closely resembled permanent hospital bed spaces, where a curtain or screens had also been added to support privacy and dignity. Where the bed closely resembled a permanent bed, the features missing were often plug sockets and piped wall oxygen, which were obtained from the neighbouring bed area instead.

3.3.24 Some trusts described how they had risk assessed the spaces that they selected and used as temporary care environments. The importance of having a multidisciplinary team, including clinical staff, estates and facilities, fire safety, health and safety, infection, prevention and control (IPC) teams, and mental health staff, doing the identification and risk assessment of temporary care environments together was highlighted. Senior staff spoke about making decisions not to use certain areas because the patient safety risks or compromise to patient quality of care were deemed to be too high.

3.3.25 One trust described how it recognised not all temporary care environments carry the same risks and so had also developed a tiered system for the different temporary care environments they used. Its standard operating procedure guided staff on which temporary care environments should be used first, and which ones should be used last.

3.3.26 Trusts said that when selecting temporary care environments, consideration was given to using spaces that were visible to staff to aid monitoring of patients. Patients can spend some time waiting to be assessed and treated, especially in an ED. There were concerns that some patients may not have been assessed and/or commenced treatment and so may be at increased risk of deterioration which may go unnoticed or be detected late in a temporary care environment.

‘Corridor patients are offloaded from ambulances and are the riskiest patients as their stability is unknown and their potential to deteriorate is greater.’

Statement from a senior sister

3.3.27 There was also a risk of falls, particularly for frail or older patients, and so selecting temporary care environments which offered good lines of sight was important. The investigation observed the challenges which come with environments that are less visible. Upon arriving on one ward, a nurse explained to the investigation than an older patient had just had a fall while getting out of their chair in a temporary care environment. Staff told the investigation that they did not have good lines of sight of the patient which may have been a contributory factor.

3.3.28 The investigation observed many temporary care environments that were placed in areas in front of nursing stations or in other visible areas of the department to mitigate the risk around limitations in visibility and monitoring. The investigation noted that some temporary care environments offered more visibility and monitoring than a normal bed space, and while this compromised privacy and dignity, it was described as safer from a patient safety perspective.

3.3.29 The investigation also observed temporary care environments that were quieter and calmer than other main areas of the ED, where lights could be dimmed and the corridor closed off in the evening to support patients’ rest and sleep. The investigation observed one large corridor that felt and looked like a hospital ward.

3.3.30 The investigation also observed corridors which were narrow, making it difficult to move another bed or trolley down the corridor. Some temporary care environments were also located in areas which were the primary access route to another department. The investigation heard how sometimes these corridors had to be quickly cleared of patients or screened off so that an urgent trauma patient could be brought through.

3.3.31 The investigation found that there can be challenges associated with the location of temporary care environments but that trusts were taking actions to mitigate the patient safety risks and improve patient experience. Many trusts were taking a risk-based approach using multidisciplinary teams to make decisions about where to locate temporary care environments.

Adaptions for patient observations

3.3.32 Challenges around keeping on top of patient observations in a busy department were highlighted. The investigation observed one hospital where electronic display boards gave quick, easy and accessible information about each patient in a temporary care environment. The electronic display board highlighted when a patient’s observations were due; if a patient’s observations were overdue, an attention-grabbing flashing red box would appear around the patient’s name. This supported staff in keeping on top of patient observations to enable timely detection of a patient who may be deteriorating in a temporary care environment.

3.3.33 The investigation was also shown a digital observation system being used throughout an ED which had been extended to incorporate beds/trolleys in the temporary care environments being used. The system highlighted the location of the patient.

3.3.34 The investigation attended an urgent and emergency care learning event where one hospital discussed that they were trialling ‘wearable monitoring’ for patients in temporary care environments with a central system at the nurses’ station that would actively support recognition of a deteriorating patient. The hospital reported some challenges around staff remembering to put the monitor on the patient, especially when busy, and some electrical issues where the monitor would power down. However, it was reported that the system had identified patients who were deteriorating and saved nursing time. The trust was yet to formally evaluate the trial.

Assessing individual patient risks

3.3.35 Decisions about which patient was appropriate for a temporary care environment were also being made between medical and nursing staff. In most cases, staff made their decision based on who was at a lower clinical risk. The investigation found that hospitals had policies and risk assessments for selecting patients to be cared for in a temporary care environment. The policies had exclusion criteria outlining which patients should not be placed into a temporary care environment. The exclusion criteria varied between hospitals; however, examples of patients who would not be placed in a temporary care environment were those who:

- had a high national early warning score (a national scoring system based on a patient’s physiological measurements such as blood pressure, breathing rate, oxygen saturation, heart rate, level of consciousness and temperature)

- required heart monitoring

- required oxygen

- were assessed as a very high risk of having a fall

- were mental health patients

- were a child or young person (below 18 years old).

3.3.36 Many frontline staff described challenges around identifying the “most well unwell patients” who might be suitable to be placed in a temporary care environment on a ward. They said that it was not an easy decision because they felt they could not provide the best nursing care for those patients.

3.3.37 The investigation did not observe children and young people being placed into a temporary care environments. However, research into temporary care environments found that in March 2025 that some children and patients with mental health needs had experienced care in a temporary care environment in the ED (Trainee Emergency Research Network, 2025).

3.3.38 The investigation noted that patients placed into a temporary care environment tended to be more elderly. Age UK told the investigation that ‘Evidence shows that long waits in A&E and Corridor Care are not experienced only by older people but they are much more common among this age group, and so this issue disproportionately impacts some of our most vulnerable older people.‘

3.3.39 The investigation also observed that some hospitals had several patients in mental health crisis who were occupying cubicles in the ED whilst they waited for a mental health assessment or required admission to a mental health hospital under the Mental Health Act (1983). This resulted in an increase in physical health patients on the corridor.

3.3.40 Staff told the investigation that they were making complex decisions about patient placement into and out of temporary care environments with the patient’s individual needs, risks and the environment being considered. They reported that they tried to put the most well patients in a particular setting into the temporary care environment. For example, they would place patients who were waiting for test results, due to be discharged or were at low risk into the temporary care environment before the more unwell patients. This sometimes involved moving a patient from a hospital bed into a temporary care environment so that a newly admitted, more unwell patient could be placed into the permanent bed. This practice was often referred to as ‘reverse boarding’. Or, if a patient in a temporary care environment deteriorated and became more unwell, they may be moved back into a designed space so that they could be monitored more closely. Staff said that this required a “whole team” approach to monitoring patients and required a culture of psychological safety in which any member of staff could approach any other member of staff to raise a concern.

3.3.41 The investigation also observed where staff had to make adaptions based on patient risk. While on a ward, the investigation observed a patient who had deteriorated in a waiting room and had been transferred to a trolley and placed in the doorway to a bay. This meant that the bay access was restricted, but there was reported to be no other safe option for this patient.

3.3.42 It should be noted that not all departments were placing the most well person into a temporary care environment. The investigation heard from one hospital that patients arriving in the ED were often moved from ambulances to a temporary care environment without having been assessed by a doctor, and that this increased risks to patient safety.

3.3.43 The investigation also heard about times when working in line with the hospital’s temporary care environment policy was not possible and patients who met the exclusion criteria had to be placed in a temporary care environment. For example, as part of a concurrent HSSIB investigation into mental health crisis, it was observed that patients with mental health needs were placed on a corridor.

3.3.44 The investigation observed and were told by staff that patients placed into temporary care environment were “de-escalated” and moved to a permanent bed or moved onto their next step in the care pathway as soon as possible. This meant in some hospitals a temporary care environment may only be used by a patient for a short period of time (for example, up to 1 hour). However, there were reported challenges around moving patients out of temporary care environments when the acuity of other patients, or the number of patients who met the temporary care environment exclusion criteria, was high. When this occurred, the investigation was told that patients could spend a few days in a temporary care environment.

Adaptations to the physical environment

3.3.45 Several nurses shared a patient safety concern around calling for help and responding to a medical emergency in temporary care environments. They said this was because the patient may be at the end of a corridor, and in many cases out of the line of sight of the central part of the ED. A few incidents where patients had collapsed in a temporary care environment were reported to the investigation. While there was no evidence of the temporary care environment itself or the emergency response impacting on the patient’s outcome, there were concerns about the impact it had on the timeliness of the emergency response.

‘I have had a patient collapse on me and been unable to pull an emergency buzzer as there are none. I had to shout and wait until someone heard me. Every second in that situation feels like a lifetime, managing the situation alone and the sense of relief when someone hears you is immense.’

Statement from a senior sister

3.3.46 The investigation observed there were often no emergency call bells in temporary care environments, especially those located in corridors, which made it difficult to notify staff when and where an emergency was occurring.

3.3.47 The investigation observed that to mitigate the risk relating to emergency response, two hospitals had installed an emergency call bell system in their temporary care environments. Another trust had provided staff with voice-activated communication devices which meant staff could quickly and easily speak to each other to seek clinical advice or reach help quickly in an emergency.

3.3.48 Some hospitals had given patients portable call bells to help them attract staffs’ attention. However, the investigation heard that these call bells often went missing, placing reliance on other patients nearby to support patients with no call bell in gaining a staff member’s attention. This presented a risk around not being able to notify staff if there was a concern.

3.3.49 The investigation observed some temporary care environments which had installed plug sockets which enabled the beds to be electrically operated, reducing the risk of falls and manual handling injury to staff, and aiding patient comfort. The sockets could also be used for medical equipment if needed.

3.3.50 To mitigate the risk of limited access to medical equipment, environments had been adapted to have key equipment near or within the temporary care environment, including mini nursing stations with computers.

3.3.51 The investigation noted that a careful balance was required when adapting spaces, as doing so could have a knock-on effect on other areas of care. For example, the investigation observed a stroke rehabilitation gym which could be converted into a ward if required. However, this meant loss of the rehabilitation space which the investigation was told can have a long-term detrimental impact on post-stroke patients on recovery of function. This could also increase the patient’s length of hospital stay in their department and reduced patient flow.

3.3.52 The investigation noted that in hospitals where many mitigations and adaptations to the environment had been made, caring for people felt calmer and looked more organised than temporary care environments in hospitals that did not want to adapt spaces for fear of normalising this type of care.

Figure 5 Example of an adapted temporary care environment with oxygen, electric plug sockets and suction

Staffing adaptations

3.3.53 The investigation found that some hospitals were taking action to ensure that staff to patient ratios were not compromised by the use of temporary care environments. Staff levels were based on the number and acuity of patients. The investigation observed temporary care environments with reportedly ‘good’ 1:4 staff to patient ratios, with additional health care assistant support. Having good staff to patient ratios meant quality of patient care was not compromised as much.

3.3.54 To achieve the needed staffing ratios, some hospitals described moving nursing staff from different areas of the hospital to support temporary care environments in the ED. This was reported to induce risk as the staff may have limited experience of working in the ED and it placed increased workload and pressure on the staff who remained on the ward.

3.3.55 The investigation spoke to a hospital that reduced the risk of staff having limited experience by rotating staff into its ED, which allowed staff to gain wider experience. Other hospitals were considering offering familiarisation training to support staff who may be required to support the ED.

3.3.56 Some hospitals used bank and agency staff to support their EDs. The investigation was told that the staff they used often worked in their hospitals and had experience in emergency medicine or were trained in the care of people with mental health illness. The investigation spoke to several bank and agency staff caring for patients in temporary care environments and they all stated that they were either experienced ED nurses but in a different hospital, or had recent experience in the current setting as a full-time nurse. Senior staff said that having consistent staffing was important, as it helped “maintain standards of care, aided communication and relationships amongst the team and staff knew where to find things”.

3.3.57 In many of the ED corridors the investigation visited, nurse supervisors had been assigned to manage temporary care environments; in some cases these comprised up to 24 extra care spaces. Their role was to provide oversight of the temporary care environment, by being able to stand back and identify concerns that others delivering care might not see. They also had oversight on when patient observations were needed. One nurse described having “a laser focus on ensuring obs [observations] are carried out, because it is an early warning of deterioration”. Having oversight of temporary care environments by healthcare professionals was reported to be beneficial and supported reducing patient safety risks.

3.3.58 The investigation observed that for patients with mental health needs who were in a temporary care environment awaiting a mental health inpatient bed, where possible, agency Registered Mental Health nurses were booked to help provide care. Alternatively some hospitals operated an enhanced care model with experienced healthcare support workers providing one to one care.