Context for this review of maternity and neonatal services

This report is a summary of information HSSIB collected during an exploratory review of maternity and neonatal services in spring 2025. This exploratory review involved meetings with 17 stakeholders and a review of 35 safety concerns submitted to HSSIB and one report published in 2021 by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB), the precursor organisation to HSSIB. Although we consider this information to be limited in its breadth and depth compared to a full HSSIB investigation, the exploratory exercise did provide evidence to support the direction any future investigations might take.

On 23 June 2025, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care announced a national investigation into maternity and neonatal services. The intention is that this investigation will be rapid, system wide and report in December 2025. In light of this announcement, we paused our intention to progress investigations into maternity and neonatal services, recognising that it would be prudent to wait for the outcome of the national investigation. However, we considered that the information we collected during the exploratory review was important and could assist the national investigation. Therefore, we decided to publish this summary report.

Executive summary

During spring 2025 we undertook an exploratory review of maternity and neonatal services with the intention of using the information we collected to inform potential areas for investigation. Following the announcement of the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care’s national investigation into maternity and neonatal services in June 2025, we have paused this work.

We are sharing the insights we gathered during this exploratory work to assist the national investigation announced by the Secretary of State. Some of these insights are consistent with the areas identified in other investigations and reviews of maternity care, while others have emerged from the information we have gathered.

Our exploratory review identified the following areas that require further investigation:

- the national structures responsible for providing direction and oversight for maternity services

- local governance arrangements for NHS maternity services and their relationship to national bodies

- the standards and approach of local investigations when things go wrong

- education, training and professional standards for clinicians providing maternity and neonatal services.

It also identified the following themes arising from stakeholder interviews:

- Some improved outcomes

Some progress has been made in maternity and neonatal outcomes, staffing levels and governance arrangements. - Complex national infrastructure

National maternity and neonatal systems are overly complex. - Collaboration and information sharing between national organisations

National collaboration efforts are inconsistent and variable. - Development, oversight and implementation of recommendations

Too many recommendations exist, with limited implementation. - Local governance arrangements

Local governance of maternity services often operates in isolation from the wider organisation. - Risk awareness

Services still lack the consistent ability to identify and respond to clinical risks. - Potential for learning in maternity and neonatal services

There is limited potential to learn from harms that happen to women and babies during pregnancy, labour and birth. - Compounding patient harm

Patients experience compounded harm due to issues within the wider healthcare system, particularly the way local investigations are carried out or the way complaints/concerns are managed. - Compounding staff harm

Staff are also affected by cumulative stress and harm. - Inequalities

Disparities in care and outcomes persist because of health inequalities. - Training and standards

There are concerns about the standards set in undergraduate and postgraduate education and whether these can be adhered to in practice.

1. Background and context

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 The Health Services Safety Investigations Body (HSSIB) was established by legislation as an independent investigation body in October 2023. We receive information from families, organisations, staff and patients that highlights safety concerns across a range of healthcare services. We use the information from safety concerns reported to us to inform our investigations.

1.1.2 From October 2023 to June 2025, we received 35 safety concerns that related to either maternity or neonatal services. This equated to approximately 10% of the total concerns we received during this period. The safety concerns highlighted issues across the entire maternity and neonatal care pathway. In addition, the safety concerns were reported by a wide range of individuals, including people who had experienced either baby loss or serious harm while using maternity services, and wider family members and staff.

1.1.3 Given these reported concerns, HSSIB carried out exploratory work to consider the potential of conducting a number of investigations into patient safety risks within maternity and neonatal services. This involved talking to a wide range of stakeholders and considering previously published reports highlighting concerns relating to maternity services, as well as safety concerns we had received from parents, families and staff.

1.1.4 From this exercise we developed four key areas for potential maternity services investigations that focused on the wider organisation of the system. Although we have now paused any further work, we decided to publish this exploratory review looking at maternity and neonatal services with the intention of assisting the Secretary of State’s national investigation.

2. How we produced this report

2.1 We used three different information sources for this review:

- 35 safety concerns submitted to HSSIB through our web portal between October 2023 and June 2025

- 17 stakeholder interviews with individuals and representatives from interested organisations

- a report we had published as HSIB in February 2021, before HSSIB was established as an independent arm’s length body.

2.2 Of the 35 safety concerns, the majority were from patients and staff, with the remainder coming from regular meetings with regional/national organisations. Most of the concerns reported from October 2023 to June 2025 took place in the past 18 months. All the safety concerns reported dealt with either very serious harm or death, with the majority of reported concerns taking place during labour. These concerns are discussed in more detail in section 3 of this report.

2.3 We interviewed 17 stakeholders, including individuals and representatives from relevant national organisations. These themes are discussed in more detail in section 4 of this report.

3. Safety concern reports

Safety concerns are reported to HSSIB by members of the public and healthcare staff through a form on our website or by email. In addition, HSSIB staff receive safety concern reports following their attendance at national and regional forums. We also collect reports from national publications, such as safety alerts. Although we do not investigate individual concerns, we encourage people to report their concerns to us as this provides valuable information which, when considered alongside other intelligence, can inform potential national investigations.

We reviewed all the safety concerns reported to us relating to maternity and neonatal services and identified key aspects of these reports. We received safety concerns reported by women and families from across all NHS England’s regions.

3.1 Who is reporting safety concerns to HSSIB?

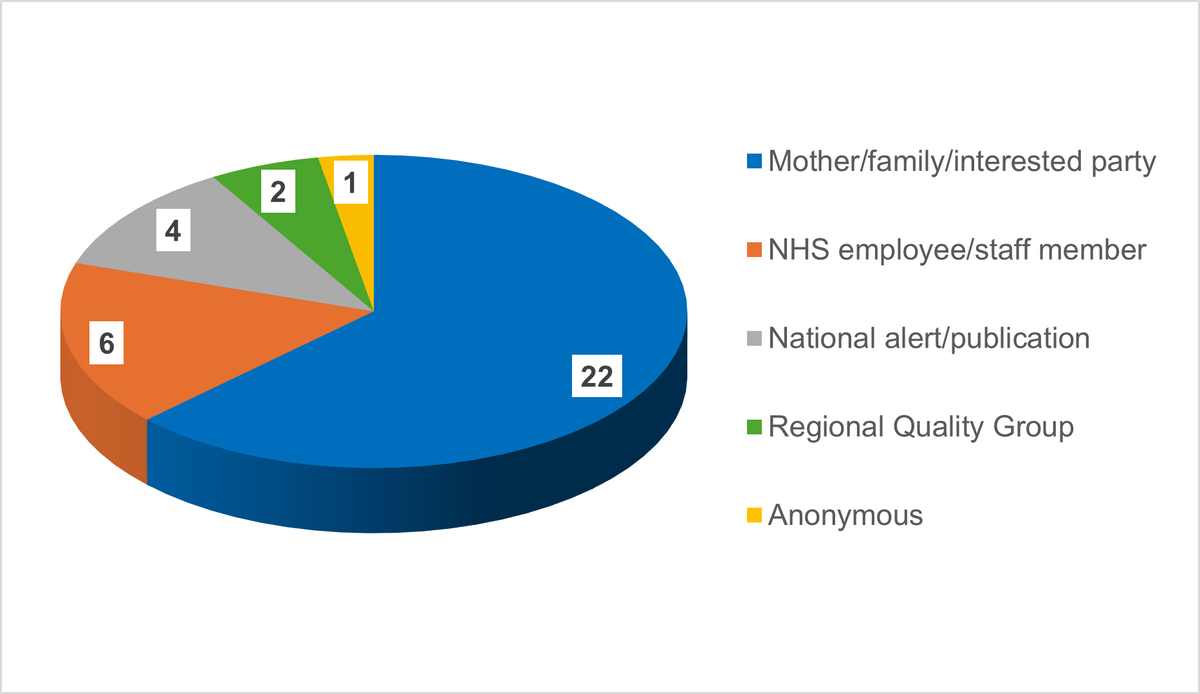

3.1.1 From October 2023 to June 2025, 35 safety concerns relating to maternity and neonatal services were reported directly to HSSIB, from the following sources:

- reports from individual women, families or other interested parties

- national reports or safety alerts

- NHS employees/staff members

- Regional Quality Group.

The number of concerns from each source is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1 Number of safety concern reports by source

Source HSSIB Insights database October 2023 to June 2025

3.1.2 The number of safety concerns reported to HSSIB by individuals and NHS staff is small compared to all the reports of harm to women and babies. However, we considered that it was important to analyse the concerns reported to us and use the information to inform possible areas for an investigation. We analysed some aspects of the safety concerns reported to us, including the year in which the event took place, the type of safety concern, the nature of the harm and at which point in the woman’s pregnancy it occurred.

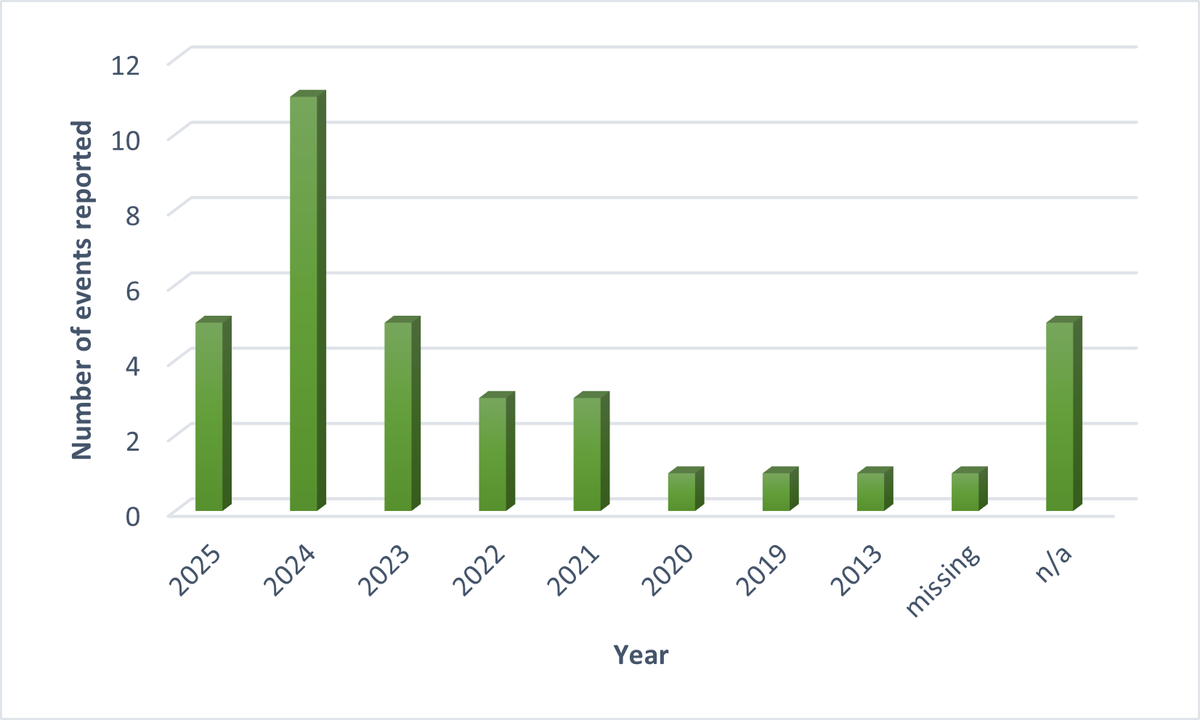

3.2 Year in which the event took place

3.2.1 We were interested to understand when the events being reported to us happened. We considered this was important because it could provide an indication of what is currently happening in maternity and neonatal services rather than what has happened historically.

3.2.2 Public inquiries typically hear evidence about past events, unless there is a clear intention to include evidence of current practice and how the system currently works. This approach may limit future improvements when it enables the system to respond to concerns by saying the system has changed and does not work in that particular way anymore. This can undermine findings regarding past events if practice has since been updated.

3.2.3 We found that the majority of events reported to us happened in the recent past, with only three of the events reported by families and staff taking place before 2021 (see figure 2).

Figure 2 The year in which reported events took place

Source HSSIB Insights data October 2023 to June 2025

3.2.4 We considered that this was an important finding as it supports any future investigation being firmly focused on current practice and current system working.

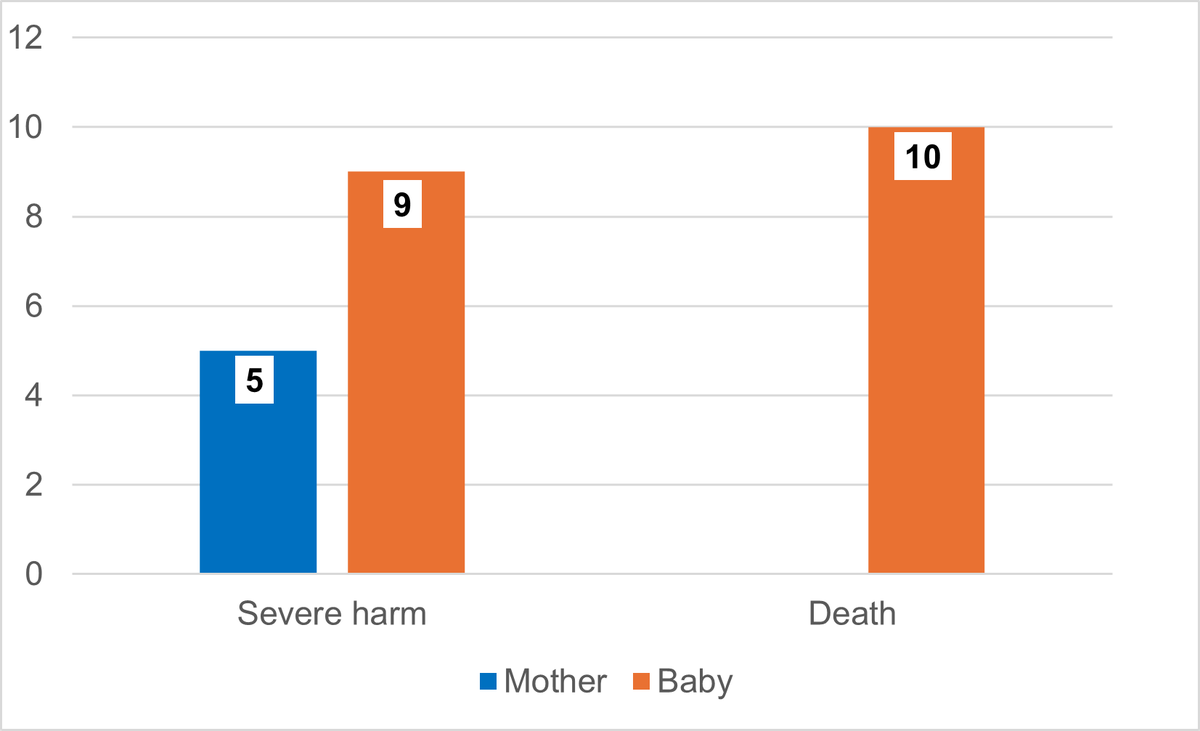

3.3 Consequences of the safety concerns reported

3.3.1 From the 35 safety concerns reported by members of the public and healthcare staff, we collated how many deaths had occurred and how many events had resulted in serious physical harm to either the mother, baby or both (see figure 3).

Figure 3 Consequences of reported safety concerns

Source HSSIB Insights database October 2023 to June 2025

3.3.2 The total number of incidents where death or serious physical harm occurred was 20. Some events reported harm to both mother and baby, or included multiple births. The deaths reported were deaths of babies rather than maternal deaths (deaths of mothers).

3.3.3 We did not collate data on psychological harm, but it should be assumed that every case reported to us by an individual who has experienced either baby loss or serious harm to a family member or their child will have experienced significant psychological harm.

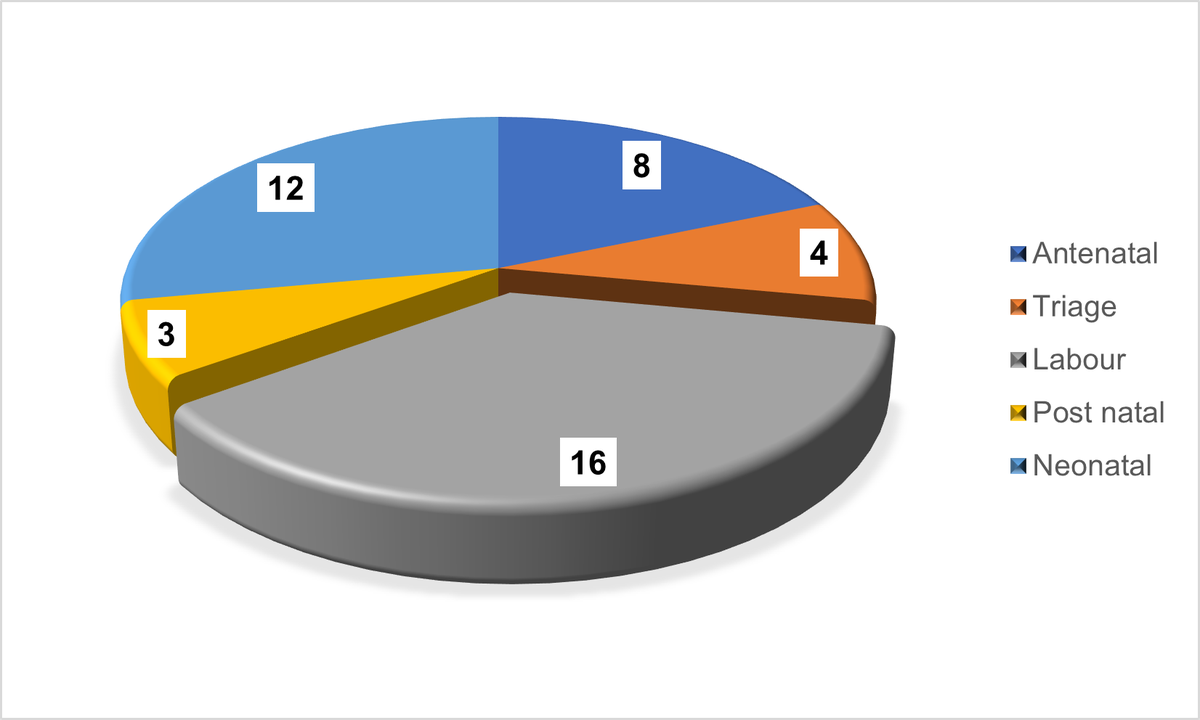

3.4 The number of reports at each stage of pregnancy

3.4.1 Of the reported concerns, 16 involved an incident that occurred during labour, with 12 safety reports being concerned with incidents during the neonatal period.

Figure 4 Stage of pregnancy in which the reported safety concern occurred

Source HSSIB Insights database October 2023 to June 2025

3.4.2 The safety concerns reported to us spanned the whole length of pregnancy through to delivery and neonatal services. However, the majority of safety concerns reported to us took place during labour.

3.4.3 As the safety concerns reported to us are a small proportion of the total events occurring, it is not possible to make any findings in terms what is happening across maternity and neonatal services. However, the safety events reported to us do involve the most serious outcomes including severe harm and death.

4. Stakeholder interviews

During our review, we carried out 17 interviews with national stakeholders. Some were individuals who had experience of national inquiries and investigation, while others represented national organisations.

From these interviews we identified 11 emerging themes relating to maternity and neonatal services. These are set out below.

4.1 There have been some improvements in outcomes, staffing levels and governance arrangements

4.1.1 We were told that current data shows that some improvements have been made in terms of reductions in the number of maternal deaths, stillbirths and rates of neonatal brain injuries, and increased staffing levels. From the patient safety perspective, clinical outcomes, such as reductions in the number of maternal deaths and stillbirths, are not always a measure of the safety of services delivered. This is because safety is just one of many factors that affect clinical outcomes. Any investigation should focus on safe systems of work, rather than purely focusing on clinical outcomes.

4.1.2 We were told that in some trusts senior leadership works more effectively.

“What we have found is that when the senior leadership team work together well, meet regularly and there is clear governance from ward to board, this shapes the service. These services are less dysfunctional.”

4.1.3 This assertion requires testing out in localities to understand the variations that exist in governance arrangements and the factors that influence any identified variations.

4.2 Complex national infrastructure

4.2.1 We were told that at the national level, the system architecture for maternity services is complex and crowded. It is unclear how priorities for service improvements are determined and how workstreams are implemented. This means there is tension between the different parts of the system. We were also told there is significant development work happening across the system for maternity and neonatal services but that this work remains uncoordinated. Any review of the system should include testing out these views and understanding their factual basis.

4.2.2 We heard that different parts of the national system can work in contradiction with one another, for example where one national agency/regulatory body, has said “everything’s fine here” and another has identified significant cause for concern. There may be examples that would illustrate this point further and support a deeper understanding of where a lack of consistency at a national level is inhibiting the development of coherent standards of care and priorities for development at a local trust level.

4.2.3 We also heard about instances where maternity-focused work by national organisations does not result in the improvement that it was designed to achieve and may act as a barrier to learning. We cannot say whether this is the case, but a review of the national architecture for maternity and neonatal services would have mapped each organisation’s identified role and how that role was being carried out.

4.2.4 The funding of maternity services was identified as an issue by many stakeholders. We heard that capital infrastructure was not funded to the level it should be and that the removal of ring-fencing for maternity funding was concerning and prevented local systems from making the recommended changes to services. We were told that there is limited improvement support when a maternity unit makes business cases for improvements. This issue would require further investigation to understand the extent of this issue and the impact of removing the ring-fencing on local spending decisions.

4.2.5 As part of a review of the national architecture for maternity services, the ability of national organisations to understand what is happening at trust level should be reviewed. We heard that national organisations focus on the delivery of ‘work as imagined’ rather than ‘work as done’ (Shorrock, 2020). In addition, there is a lack of ability in the system at a national level to hear and understand what is happening locally contemporaneously, rather than only hear it historically through national inquiries. We identified this as a critical issue that needs to be understood in significant depth if there is to be improvement in maternity services across England. It is also clear that a safety science investigation approach is best placed to achieve this, as it has the methodologies and tools to interrogate the system from local to national level, understanding how each component of the system works to influence the whole.

4.2.6 We heard that the national architecture of maternity services should be the focus of any further national investigation work because of “previous and current inquiries into patient safety being limited in that they focus on individual trusts and are predominantly focused on the front line”. The lack of focus on national organisations and the system architecture for governance and oversight means that some of the system wide factors that influence safe practice are not well understood. Therefore, the impact of the barriers to safety improvements that exist at a national level are not considered as an important aspect of overall system change.

4.3 Collaboration and information sharing between national organisations

4.3.1 We heard from stakeholders that there were too many instances when national organisations did not collaborate and share information in a way that would benefit trusts and local systems. This was true for organisations that work alongside each other and have the potential to share information.

4.3.2 We heard that there needs to be greater collaboration in terms of how organisations can align their work to remove potential duplication. As well as duplication, we heard that a lack of collaboration resulted in a lack of awareness of improvements being made and a strategic plan to co-own safety actions that result from national work.

4.3.3 We also heard the suggestion that national stakeholders should be convened to strategically oversee work that is in progress. However, this suggestion does not fully consider the limitations that exist in national bodies that are perceived as barriers to implementing change.

4.3.4 We heard there was a forum where organisations had come together to talk about the opportunities for collaboration regarding safety issues under the National Maternity Review: Better Births (2016) programme. We heard that relationships had been developed which were effective in promoting collaboration, but the standing down of this forum meant that they were no longer operative. There is an appetite from stakeholders to be able to work together.

4.4 Development, oversight and implementation of safety recommendations

4.4.1 The development, oversight and implementation of safety recommendations for maternity services was identified as a problem by many stakeholders. We heard there were too many recommendations and no organisation with clear accountability for tracking their implementation.

“It is a huge problem that we keep adding more and more recommendations. Organisations who make safety recommendations don’t have a regulatory responsibility to follow up. It is for the trusts to pick up, but which recommendations are they supposed to prioritise and pick up?”

4.4.2 There is recognition that safety recommendations are made with good intentions but that there are far too many recommendations to manage.

“In a clinical context when you have limited time and resources, how do we make it practical for people to streamline? This issue of many recommendations is felt most sharply in maternity – it is the question of ownership. Lots of bodies have a piece of the jigsaw but who has overall accountability to ensure the jigsaw comes together as a whole? The ownership doesn’t exist from a regulatory perspective.”

“… there are those recommendations that come out, you know with every single report, but no one is really following through on it like there’s no one that’s then saying ‘we wrote this in our report, what are you doing about it?’”

4.4.3 One stakeholder commented that “maternity is well investigated, using traditional methods … why hasn’t that led to greater change?”. This question was echoed in discussions with many stakeholders. The reason why investigations and recommendations have not led to greater change is an area we would examine in any national investigation.

4.4.4 Stakeholders recognised that the system was under significant pressure at both local and national level and was struggling to respond to the number of recommendations published, particularly in light of the challenges of accommodating national and local reorganisation.

4.4.5 We heard a level of disillusionment among stakeholders regarding the ability of recommendations to bring about the required change.

“The same stuff get[s] rehashed that we know doesn’t work.”

4.4.6 To counteract this disillusionment, any investigation would have to review, from a systems perspective, the barriers to implementation of recommendations made. HSSIB has acknowledged these challenges and has begun work in this area, in partnership with other stakeholders, via our Recommendations but no action: improving the effectiveness of quality and safety recommendations in healthcare report and ongoing work in partnership with the National Quality Board.

4.5 Maternity service governance structures in local trusts

4.5.1 We heard that maternity units may have different governance structures from the rest of the trust. This creates the potential for maternity units to work in isolation and not be subject to the same level of oversight as other services in trusts. Given the importance of the appropriate level of oversight and scrutiny for maternity services, it is important that governance structures are able to provide this at a local level. A review of local providers should include a detailed review of governance structures to understand the amount of local variation and the effectiveness of the different governance structures.

4.5.2 We heard the following:

“They [maternity services] have a mini governance within maternity and work in parallel to report to the board. It means…less scrutiny – what gets to board is not intentionally misleading and they ‘start to believe their own narrative’.”

4.5.3 We were told that maternity units do not always feel part of a trust and feel like separate organisations. We heard that often maternity services are “disgruntled” and not treated as part of a trust but also that maternity services do not wish to be treated as part of trust services. We do not know the extent to which this is the case across England, but it is an issue which should be explored in any review of local providers.

4.5.4 We heard how local governance arrangements could undermine the efforts of national organisations to implement safety measures. It is difficult for national organisations to resolve issues which lie firmly within the responsibilities of trust boards.

4.5.5 An example of this is triage arrangements for maternity. Although triage should be designed to be appropriate to the specific service being offered, we heard about basic triage arrangements in maternity that would not be tolerated in different areas of trusts such as emergency departments.

4.5.6 We heard about a lack of confidence in senior management, a lack of autonomy to make decisions about services and the existence of a blame culture throughout maternity services.

4.5.7 We heard that at board level, reporting lines for maternity services can be through different governance mechanisms compared to the rest of the hospital. We heard that these different reporting routes may result in a perceived loss of status in maternity. An example given was where maternity safety is being managed differently to other serious clinical risks. This may contribute to a lack of coherence with other safety initiatives.

4.5.8 From these perceptions, it is clear that the governance systems for maternity and neonatal services should be included in any investigation. In addition, an investigation would need to identify how far the difference in governance systems act as a barrier to implementing change.

4.5.9 An extension of this point is the need to define an accountability framework for maternity and neonatal services, and embed maternity indicators in this in the same way as other services. We heard that information held on trust dashboards does not always match the data held nationally which makes it difficult for national organisations to have contemporaneous oversight. If the governance in a trust is not providing the level of oversight required, there is a mismatch of data held locally and nationally, and it becomes difficult to have visibility of an emerging safety situation. This is an area that requires further investigation

4.5.10 We heard that stakeholders found the lack of oversight in trusts concerning and there were concerns about the quality of leadership in maternity services at a local level. We heard about a lack of confidence in senior management and the existence of a blame culture throughout maternity services.

4.5.11 We also heard there are units that have got it right in terms of governance and deal with issues such as very challenging staffing positions well. However, we also heard there is limited understanding of the conditions that have enabled these units to function well – that is, what is it that makes their units operate safely and effectively? This is an area that has the potential to provide national learning across England.

4.5.12 We heard that funding streams for maternity services might influence trust boards’ interest in providing robust oversight. We heard that the way budgets are allocated to maternity service by trusts and integrated care boards might be a feature of the problems with leadership and governance. This was particularly the case in respect of claims made against trusts for maternity cases and incentives that exist for trusts. Again, careful investigation would be needed to ascertain the facts behind this perception.

4.5.13 We also heard that even when trusts do improve, there are problems with sustaining this improvement.

“Trusts seem to be performing better but it doesn’t seem to be sustainable. there is an element of assurance but when the support ends, not sure how well sustained it is. Half of maternity units underperforming.”

4.5.14 Since safety events are unevenly distributed, a period with fewer safety events can be falsely regarded as ‘improvement’. This means that underlying system issues may not always be recognised or addressed. An investigation could examine this matter in more detail.

4.6 Recognition of risk

4.6.1 For stakeholders, the issue of local services’ response to clinical risks was a high priority. Stakeholders gave many examples of where services had failed to anticipate and/or respond to the clinical risks associated with pregnancy, labour and birth. Some examples are given below.

“People with additional care needs not in the appropriate place … women with arterial lines on the post-natal ward … the staff, aren’t trained and competent to be able to look after these deteriorating women …’

“… they [staff] were downgrading levels of harm for women who had experienced a 3rd or 4th degree tear. Major obstetric haemorrhages were being rated as low or no harm ... ’

“… we’re still not getting the harms reported consistently. They’re not taking into account, you know, you’ve got a family member who’s seeing their wife exsanguinate [bleed out] on a table … They’re not recognising that level of harm to the mum or baby.”

4.6.2 We heard about the normalisation of harms that happen during pregnancy, labour and birth which detract from the ability to fully understand and respond appropriately to a deteriorating clinical situation. We also heard that trusts are recording and reporting levels of harm for women and babies inconsistently and in a way that does not fully represent the potentially life-threatening situations that have occurred.

4.6.3 We were given the example of a healthcare assistant acting as the first assistant during a caesarean section and neither clinicians nor managers considering this to be a risk. This was compared to the approach in general surgical theatres, such as ophthalmology, where surgical first assistants would always be a qualified healthcare professional.

4.6.4 It was particularly concerning that the normalisation of harm in maternity care was reported in 2015 in the Morecambe Bay Investigation and is still being identified as a problem in 2025.

4.7 Potential for learning in maternity and neonatal services

4.7.1 We heard repeatedly that the system was not learning from past events, incidents, litigation or national inquiries in the way that would be anticipated. This issue requires further exploration in terms of the type of learning that would be expected and the barriers that exist across the system that prevent learning from being adopted.

“Why don’t we benefit from learning? Defensiveness, Board concern about reputation. As a leadership group, key challenge is breakdown in trust between front line services and national leaders, and between people who use services, including bereaved families, and organisations.”

4.7.2 We heard about perceived issues relating to the training and education of midwives that stemmed from changes to education in the 1990s. One stakeholder told us that as soon as they entered university to study as a midwife, normal birth was emphasised over any complications that may occur. They felt normal birth was emphasised to the detriment of understanding potential complications.

4.7.3 We also heard about a disconnect sharing learning across different organisations. This should be further investigated using a model that identifies how the whole system operates.

4.8 Compounded harm for patients

4.8.1 We heard how the harms suffered by women, families and babies can be compounded by their treatment following an incident. This includes harm caused by treatment during the incident itself, subsequent trust investigations and formal legal proceedings such as inquests. We heard that these events can further compound the harm caused by the incident itself.

4.8.2 We heard that the investigation process following tragic events such as the deaths of mothers and babies is traumatic and that staff and trusts can lose sight of compassion during this process. We heard that there is a huge variation in whether women and families feel listened to during this process and this variation reflects differences in culture – that is, how open staff are depending upon the culture within the service. We heard that some trusts are so focused on reputation management that staff are afraid to say sorry and be open with women and families.

4.8.3 We also heard that formal proceedings may create circumstances in which trusts adopt an adversarial position to protect themselves against litigation costs. Formal legal proceedings can create defensiveness on the part of trusts. It was pointed out that families do not receive the same support as families during formal proceedings such as inquests where trusts are able to appoint a legal team. The legal process could form further harm to families in these cases.

4.8.4 We heard that compounded harm is having a significant impact on families and is part of a narrative that creates fear among families using maternity and neonatal services. We were told that the public narrative around maternity services is “toxic” and scaring women from having their babies in hospital.

4.8.5 It was suggested to us that this fear was behind the rise in caesarean section rates. This suggestion would have to be fully investigated to understand if there is any link between a perceived fear among the public or whether there are other factors influencing any implied rise in caesarean rates.

4.8.6 Stakeholders were concerned about the unknown harm to women and families resulting from their experiences of maternity services and wanted to see more work being undertaken to understand the impact on women and families when things go wrong.

4.8.7 Stakeholders discussed the importance of a trauma-informed approach to investigations and dealing with families who have been harmed in the ways described above. Trauma-informed care and associated approaches are grounded in the understanding that a patient’s past exposures to trauma will have influence on their development and how they respond to situations. We also heard the need for and importance of restorative practice. to prevent conflict, build relationships, and repair harm by enabling people to communicate effectively and positively.

4.9 Compounded harm for staff and maternity services

4.9.1 We heard that following high-profile maternity investigations and inquiries, maternity services are experiencing a drop in public confidence, which is damaging professionals’ confidence in particular services. This can make it difficult to recruit professional staff.

4.9.2 We were told about midwives receiving death threats and being berated “in the schoolyard” for being part of a service that is regarded as “failing”.

4.9.3 We heard that following exposure of failings in services the failure narrative itself becomes damaging and that it is difficult to understand whether the service is currently performing differently or whether its profile is causing the problems. For example, we heard examples where women would not go to certain hospitals that had been the focus of national investigations.

4.9.4 Stakeholders told us about clinicians taking a risk-averse approach because of the fear of blame. We heard that this defensiveness drives the behaviour that compounds the harm women and families experience.

“… your registration is on the line, drives defensiveness – response from defence organisation is don’t say anything.”

4.10 Health inequalities

4.10.1 We heard that there are well-researched health inequalities in relation to maternity care, particularly with regard to ethnicity, social class and deprivation. However, we also heard that despite the evidence base for these inequalities, maternity services are delivered with a lack of focus on equality.

4.10.2 Stakeholders told us that health inequalities should be included when thinking about maternity services. We were told that patients within affected groups typically have lower advocacy in the NHS. Any investigation should include a focus on health inequalities across a range of areas.

4.11 Education, training and maintaining professional standards

4.11.1 Stakeholders told us of their concerns about standards of training for professionals working in maternity and neonatal services in terms of education, training and the maintenance of professional standards throughout their career – from undergraduate level to senior clinical positions. We were told that professional competencies for midwives include understanding a situation where a mother’s/baby’s health is deteriorating and training for high dependency units.

4.11.2 We heard that a “toxic culture” can occur in maternity services, often relating to differences in approach to intervention and non-intervention for maternity care. We heard of tribalism in respect of the different approaches, where staff do not feel able to uphold standards and feel bullied and harassed. They also fear being accused of bullying.

4.11.3 We heard that there are many standards that clinicians are expected to adhere to, but these are not prioritised. This means that staff are trying to ‘keep their heads above water’.

4.11.4 We heard from one stakeholder that internationally trained midwives are often not integrated into teams and that there has been poor feedback through the ‘welcome to the UK programme’ about the way overseas midwives are treated.

5. HSIB report

5.1 In 2021 HSIB, the precursor organisation to HSSIB, published a national investigation ‘Learning from maternal death investigations during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic’.

5.2 This investigation identified seven finding regarding these maternal deaths:

- Unprecedented demand for telephone health advice caused delays in women accessing health care.

- Public messaging and safety netting advice caused delays in women seeking help.

- Guidance changed rapidly.

- Use of early warning scores did not always detect deterioration of women or babies.

- Personal protective equipment (PPE) requirements changed due to COVID-19.

- Staff described feelings of stress and distress which can affect performance.

- Difficulties in making a diagnosis and choosing treatment strategies.

5.3 Some of these findings relate solely to the pandemic, such as PPE requirements and rapidly changing guidelines. However, other findings relate to maternity services more generally and still apply today.

In particular, the unprecedented demand for telephone advice identified the risks present in maternity triage services prior to the pandemic that only increased during the pandemic. Triage services were also highlighted in the HSIB report Investigation report: Assessment of risk during the maternity pathway in 2023.

The problems identifying and responding to deterioration of women and babies throughout pregnancy, labour and birth were also identified in this report, as was the distress experienced by staff. These concerns have also been identified in previous HSIB annual reports Maternity investigation programme year in review 2022/23.

We consider the findings of these reports to be as relevant today as when they were published.

6. Conclusion

This exploratory review is a starting point from which further inquiry should be made. It has identified the following areas that require further investigation:

- the national architecture responsible for providing direction and oversight for maternity services

- local governance arrangements for NHS maternity services and their relationship to national bodies

- the standards and approach of local investigations when things go wrong

- education, training and professional standards for clinicians providing maternity and neonatal services.

We are sharing this information now to assist the national investigation announced by the Secretary of State in June 2025.

7. References

Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (2021) Learning from maternal death investigations during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/learning-from-maternal-death-investigations-during-the-first-wave-of-the-covid-19-pandemic/ (Accessed 11 August 2025).

Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (2023) Assessment of risk during the maternity pathway. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/assessment-of-risk-during-the-maternity-pathway/investigation-report/ (Accessed 11 August 2025).

Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (2023) HSIB maternity investigation programme year in review. Available at https://hssib-ovd42x6f-media.s3.amazonaws.com/production-assets/documents/hsib-maternity-investigation-programme-year-in-review-2022-23-accessible.pdf (Accessed 11 August 2025).

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2025) Recommendations but no action: improving the effectiveness of quality and safety recommendations in healthcare. Available at https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/recommendations-but-no-action-improving-the-effectiveness-of-quality-and-safety-recommendations-in-healthcare/report/ (Accessed 11 August 2025).

National Maternity Review (2016) Better Births. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/mat-transformation/implementing-better-births/mat-review/ (Accessed 11 August 2025).

Shorrock, S. (2020) Proxies for work-as-done: 1. Work-as-imagined. Available at https://humanisticsystems.com/2020/10/28/proxies-for-work-as-done-1-work-as-imagined/ (Accessed 11 August 2025).